The design strategy of simplification

A friend, Stuart Balcomb, a musician and composer in Venice, California, reminded me of something, to design — and Steve Jobs.

I worked as a consultant to Apple, at the behest of Steve Jobs in the late 70s, early 80s. I met him first at Stanford, at a design conference and followed up. We talked about type, calligraphy, Reed College. I spent time there, working with Lloyd Reynolds. So did he, as you likely know.

Much of my education as a “designer” [I was never formally trained as a designer, actually] was based on traveling and meeting people, spending time with them, working with them — for a bit. I did that at Cooper Union which lead to links to Herb Lubalin and Milton Glaser, Jack Lenor Larsen. Traveling to Darmstadt, Germany, I met and shared, explored the work, and my work, with Hermann Zapf. There were others, like connecting in an early inspirational spin with architect Richard Meier and later, designer Charles Gwathmey. My explorations took me all over the world, meeting people that I admired, sharing my work, getting critiques and moving on.

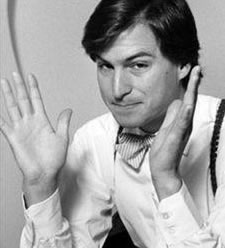

But the idea of learning works in two patterns, for one — other teachers, inspirations — and two, clients that are inspirations. My chance to work with remarkable clients doesn’t necessarily mean that they came to me, purely on the herald of reputation — but rather, I pursued them. Like this young bow-tie wearing dude, Steve Jobs.

I too, a bow tie wearer in the legacy from my father — a surgeon, now retired, and an inveterate bow tie wearer.

That pursuit of learning, connecting with ingeniously directed, intelligent clients led to others, like Clint Eastwood, the Wachowskis, Steve & Elaine Wynn, Sharon Stone, Richard Gere and a string of remarkable people.

I hunt for that — the learning,

the teachers,

the inspirational clients.

But, in working with Steve, the layering of the work was about building logo treatments for Macintosh — designing fonts, creating calligraphic treatments and running scripts, and, too — drawing icons of, and for, the Macintosh. And, usually, my first drafts were too “complicated” or — “too fancy” too luxury.

“Simplify, clean, lean”–much like the principles of product industrial design for all Apple products. Massing the layouts — then, wholly non-digital, live drafts on real paper with real ink, then, I always presented “live” work, he’d sort quickly and move to the most clean, simplified and restrained. We worked on a string of projects — for him, then others, at Apple.

Later, working at NeXT Computer with Steve, he looked for more complicated if not “illustrative” treatments for conference logo design development. That came from a booklet I’d mailed him on our work in motion picture identity.

What struck me, as a memory, was the line [that Stuart intoned] “don’t make it cute.” Not that he ever said that to me — and I can’t characterize much of my work as “cute” per se, but there is inherently a drive to beauty = making beautiful things, bringing more of that presence to the world. It was this reference, on the Regis McKenna designer, the story of Janoff’s “designing of the original Apple logo” — noted the ApplePR | Advertising alliance to Regis McKenna, that brought it back to me. Later, the 80s, we worked with McKenna’s team on Apple, Wall Data and a string of other technology brands.

Working with Steve started with a call, then “can you come down here?” A meeting, fast and focused, usually one on one. I’d learn about the scope — never as a written brief — always live. From there, I’d develop solutions and either ship them, or fly to meet live.

I’ll never forget those days.

That was then. This is now.

TSG | Girvin Decatur Island studios

…..

GIRVIN | MEDITATIONS ON

THE LEGACY OF STEVE JOBS & APPLE

DESIGNING IMAGINATION : AND THE TOOLS TO MAKE IT HAPPEN