The heart of the genuine: exploring the concepts of authenticity, history, brands and the place of luxury.

I’d open with the meaning — and the combinational character of the idea of truth fullness — and its apparent luxury in telling — are true stories the rarest of the rare? That is — is there a positioning for an authentic brand, that relates to a rarity, a a kind of luxury and uniqueness that is harder to find?

As with anything, I start with words. Because the warmth of meaning lies in the heart, the seed of the word itself; it’s perhaps only that we’ve forgotten that sometimes the content, the history of the word, is discounted. What of authentic? People keep saying that — finding authenticity — and I ponder the meaning: what’s really being expressed? What are these people talking about? Deeper seeking, what does authenticity mean?

The etymology of authenticity, springing back in time is, from 1340, “authoritative,” from Old French autentique (13c.), from Medieval Latin authenticus, from Greek authentikos “original, genuine, principal,” from authentes “one acting on one’s own authority,” from autos “self” + hentes “doer, being.” What I’m drawn to here is the concept of acting and being, forming foundations, on the premise of authorship — a “self” maker. We can all contemplate this, in what we do as people, as well as in the context of branded business.

What then, to genuine? The begetting of the linguistic string: the first referenced use is from 1596, from Latin genuinus “native, natural,” from root of gignere “beget”. Gk. genos “race, kind,” and gonos “birth, offspring, stock,” from ProtoIndoEuropean base *gen-/*gon-/*gn- “produce, beget, be born” (and there are Sanskrit expressions, deepening in the roots of meaning: janati “begets, bears,” janah “race,” jatah “born;”) and other branches –Avestan zizanenti “they bear;” Greek gignesthai “to become, happen;” L. gignere “to beget,” gnasci “to be born.” These all reach to the founding of genius “procreative divinity, inborn tutelary spirit, innate quality,” and the Latin ingenium “inborn character,” germen “shoot, bud, embryo, germ;” Lithuanian. gentis “kinsmen;” Gothic. kuni “race;” Old English cennan “beget, create;” O.H.G. kind “child;” Old Irish ro-genar “I was born;” Welsh geni “to be born”). Historically then, studying the branching of the word, the heritage of genuine is thousands of years old: the germ of truth.

There are layers of meaning here, that are intimately tied to the exploration of authentic being and the explication of genuine. What I’m getting to is the idea of the genuineness, the truth in the making, is linked to the founding principles of this character. How does that relate to business? In finding the heart of a brand — you must travel to the center — the foundational ground of the brand legacy. Profoundly authentic, and matured business consciousness, emanates from human ideas and ideals. Commerce is an outcome, but the beauty of this is about what passionately forms the intention of the enterprise in the first place.

Michael C. Gilbert, who runs a consulting group called The Authentic Organization notes:

“Authenticity isn’t some paint you apply to a product or an organization. Branding is about appearance or, at best, the consumer experience. Authenticity is about being true to yourself. This, of course, requires a self to which to be true. Unfortunately, you can be authentic without appearing so. But branding says that appearing so is more important, while integrity says otherwise.”

There are critical alignments here that relate either to currently founded or start up brands, or brand and business enterprises decades in age that are hundreds of years old. I’ve had the chance to connect with all three.

New: Tableau (one year)

Old: Capezio (125 years)

Really old: St. Mary’s and the Lasallian legacy (400 years)

What all of this comes down to is the idea of moving past the glamorous (and clamorous) spin of yet another public relationship pitch and reaching to the centerpoint of finding the truth “in the making”, as the etymological definitions from above have pointed out. Bill Breen references, in his exploration of brand reality: “In an increasingly shiny, fabricated world of spun messages and concocted experiences–where nearly everything we encounter is created for consumption–elevating a brand above the fray requires an uncommon mix of creativity and discipline. And nowhere do you see the challenge more starkly illustrated than in the quest for authenticity. John Grant in The New Marketing Manifesto reflects, “Authenticity is the benchmark against which all brands are now judged,”. Or as Seth Godin quips in Permission Marketing: “If you can fake authenticity, the rest will take care of itself.” And summarized, he intones: “Overloaded by sales pitches, consumers are gravitating toward brands that they sense are true and genuine.”

What is that?

One might presume luxury, as a business premise, could fit into this category — since, by the way, it seems to be struggling less these days than many other business offerings for consumers. Luxury, as a branded categorical enterprise, has a two way challenge; its conundrum — on the one, being intimately connected to conceptions of true authorship, on the other, a grouping of conglomerate stakes that must increase their share by adding market capacity. That very action decimates authentic production. 35 brands control more than 60 percent of the global market. As of last year, “40 percent of all Japanese people owned a product made by Vuitton — in fact, “the Japanese now account for 40 percent of all luxury sales, more than Americans (17 percent) and Europeans (16 percent) combined.” India has five million consumers of luxury goods, while China, with “200 million such consumers” (12 percent) … is expected to be the most important market in the world by 2010.” Growth, big growth internationally –but how can luxury grow and hold this sense of authorship and care in making? The point is genuineness — and can luxury be presupposed to respond to these presumptions — hold to the truth of the authentic measure? Can it be true, founded on hands-on authorship?

Good question. But the point might actually be to the character of what lies behind, beneath the layers, and in, the brand.

How to grow there? French shoe designer Christian Louboutin: “Luxury is not consumerism.” “Luxury,” says Christian, “is the possibility to stay close to your customers, and do things that you know they will love.” Christian is at the forefront of “a renaissance of independent luxury houses that offer traditional quality and personal service.” He comments: “I see these men who build luxury brands to make money and I am in the same industry but I feel nothing in common with them.” He is talking, of course, about “Prada, Gucci, Giorgio Armani, Hermes and Chanel, all of which have revenue in excess of $1 billion a year.”

Reveries.com dials in: “Not to mention “LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, a $11 billion conglomerate whose labels also include Dior, Fendi and Berlutti.” All told, such merchants of “luxury” represent “a $157 billion-a-year mass market whose products now lack the exclusivity — and in many cases the quality craftsmanship — that formed the basis for their cachet in the first place.” As author Dana Thomas writes: “Luxury was a natural and expected element of upper-class life, like belonging to the right clubs or having the right surname. And it was produced in small quantities — often made to order — for an extremely limited and truly elite clientele.” [Thomas, Dana. Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster]

According to the Wall Street Journals reference, authored by Christina Passariello, Rachel Dodes and Stacy Meichtry “Even as many Americans are pulling in their purse strings, spending on key categories of high-end luxury goods is proving surprisingly resilient, underscoring the industry’s progress at broadening its reach beyond the upper crust and into the growing ranks of the affluent.

Luxury-goods makers reported in recent days that U.S. sales of expensive jewelry, Swiss watches and French scarves are holding firm, helped by the fact that many brands now offer more entry-level items than in the past, and by foreign tourists who have money to burn because of the weak dollar. In addition, a growing number of affluent Americans are still splurging on what they perceive as investment-grade luxury goods.” That premise gestures to the promise of authenticity — there’s value there; and it is something worth committing to, as a brand relationship.

What might be inferred, here, is the idea that each of the goods noted above are about inherent value confirmed in the genuine character of “the maker”. There’s a point to truth fullness here, in the character of this specific reference. That is — is the truth being told; is the authenticity implied in brands that are based on decades of qualified production still in play?

Whose story is real? What’s the differentiation?

Sometimes it’s hard to tell — with these luxury products — and oftentimes with many others, what is the point of differentiation and distinction; what’s the distinguishment?

Dana Thomas infers in her research — that the “luxury business that once catered to the wealthy elite has gone mass-market and the effects that democratization has had on the way ordinary people shop today, as conspicuous consumption and wretched excess have spread around the world. Labels, once discreetly stitched into couture clothes, have become logos adorning everything from baseball hats to supersized gold chains. Perfumes, once dreamed up by designers with an idea about a particular scent, are now concocted from briefs written by marketing executives brandishing polls and surveys and sales figures.” [Thomas, Dana. Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster]

The quote from Tom Ford, in a talk that he gave in Moscow, for the International Herald Tribune’s Luxury Summit there, speaks to content, value, intention and truth in reflectivity behind brands. That it is one thing to have a “logo”; it’s another to have something meaning full, behind it.

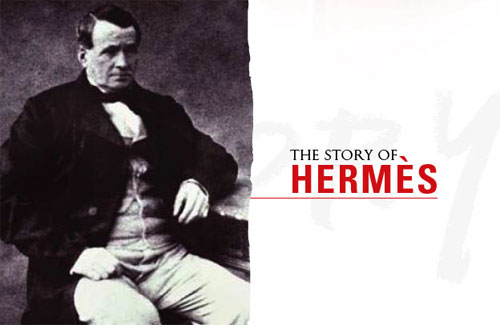

High-profile luxury brands like Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Cartier were founded in the 18th or 19th centuries by artisans dedicated to creating beautiful, finely made wares for the royal court in France and later, with the fall of the monarchy, for European aristocrats and prominent American families. Luxury remained, writes Ms. Thomas, “a domain of the wealthy and the famous” until “the Youthquake of the 1960s” pulled down social barriers and overthrew elitism. It would remain out of style “until a new and financially powerful demographic — the unmarried female executive — emerged in the 1980s.”

And with that renewed vigor in the market for luxury — authentically authored objects of distinction — the strategies for truth devolved. As both disposable income and credit-card debt soared in industrialized nations, “the middle class became the target of luxury vendors, who poured money into provocative advertising campaigns and courted movie stars and celebrities as style icons. In order to maximize profits, many corporations looked for ways to cut corners: they began to use cheaper materials, outsource production to developing nations (while falsely claiming that their goods were made in Western Europe) and replace hand craftsmanship with assembly-line production. Classic goods meant to last for years gave way, increasingly, to trendy items with a short shelf life; cheaper lines (featuring lower-priced items like T-shirts and cosmetic cases) were introduced as well.”

Dana Thomas further summarizes that “The luxury industry has changed the way people dress,” she writes. “It has realigned our economic class system. It has changed the way we interact with others. It has become part of our social fabric. To achieve this, it has sacrificed its integrity, undermined its products, tarnished its history and hoodwinked its consumers. In order to make luxury ‘accessible,’ tycoons have stripped away all that has made it special.

“Luxury has lost its luster.”

<

<

But not all could fall to this positioning — there are still brands, legacy brands, that espouse a philosophy that holds to the character of individuality — and, going back to the origins of this discussion, the character of truth and genuine “generation”. And, to the explorations of true brands, what I’ve found is that many of them exist in the realm of what one might define as luxurious in intention. That might be a broader ranging topic, but who’s there? Who, in the category of luxury — and in other branding premises and promises in relationship, lives in the space of truth?

I’d offer, for one — Hermès.

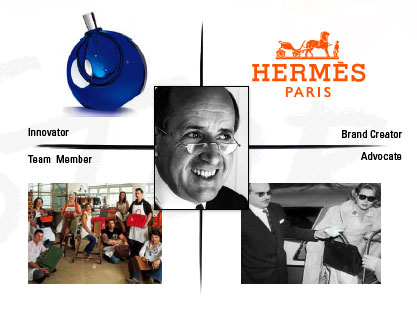

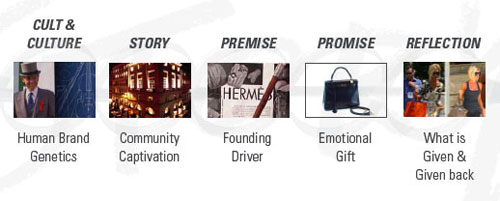

There are developments of examination to Girvin’s method to explore the components of a brandstory and what that can mean to the heart of the brand telling – the character of its authenticity. These one might apply to the characterististics of any brand that is in a point of evaluation to reflect direction. Noted below, these array in manner of examination and explication. First off, any brand that has a heart has a human being at the center of it — and this is the empowering legacy of Hermès; there’s generations of family attention and character that drive the detail(ing) of the brand. What’s unique about Hermès is that they’ve managed to remain “unheld” — not owned by massive conglomerates, but are a family “clan”.

Todd Eberle photo

Hermes likes to call itself “a firm apart”, resisting predatory takeover artists who have swallowed up such venerable family strongholds as Louis Vuitton and Lanvin. A steadfast refusal to license its name to sell discount luggage a la Pierre Cardin or mass-produced hosiery a la Christian Dior.

The real character to differentiation is its stubborn adherence to century-old manufacturing techniques. “Hermes is an anachronism,” says Gene Pressman, executive vice president of Barney’s, the upscale clothing chain. “It’s about quality that’s made to last.”

There’s a modeling that we consider, in exploring this brand premise — Hermès is about a wealth of truth; it’s about storytelling in the truest sense of the word, that the work that they do, what they make, it’s a returning and evolving legacy of creativity.

While Hermes moved its workshops and offices to larger quarters in the Paris suburbs this past spring, Dumas steadfastly assures the truth of the brand — that the company’s standards must never suffer. In certification of standard, he recently restructured the firm into a limited partnership that sets up a “Fort Knox” of family control, even if Hermes makes a public stock offering — a very distant proposition. The Dumas, Hermés, promise: “We will continue to make things the way the grandfathers of our grandfathers did.”

This mapping, above, speaks to the code of the brand — a sense of culture — the cult of community, a long-running and consistent application of legend building and truthful captivation; it’s about the premise of the handmade, the promise of an emotionally empowering bridge — which results in reflectivity; what is given to the brand guest — and what the guest will give back in a continuing, resonant relationship.

There’s more to explore on the concepts of authentic branding and truthful marketing connection. I’ll reach to those, next. And of course, I’d be interested in hearing your thinking, on that front.

Tim Girvin | NYC

http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2007/09/hermes200709

http://lesailes.hermes.com/us/en/