Conceptions of Brand-related built environments for storytelling in contextual community.

First off, a reference to the Oakley Headquarters—an environment designed and dedicated to the spirit of innovation that drives the brand and

the creation of their products; built tough.

Entry | Oakley HQ | Located here

A note on GIRVIN’s core philosophical principle—towards holistic impression backgrounder: people understand brand comprehensively in-place.

Touch, sound, scent, sight, taste—integrated.

Over the last 50 years, Girvin has been working in the space of creating branded environments. These expressions might be conceptual, like our work for Yves Saint Laurent, or functional, like our partnership with Dawn Clark, AIA LeedAP on finding brand story in patterning applications for retail. Or brand linguistics in café brand development—franchised, or solo well-making experience design language.

Even corporate museums can be defined as a form of brand architecture—

like our Microsoft brand storytelling.

Personally, historically, GIRVIN has worked with architects for more than 40 years of collaborations. I grew up in a neighborhood of architects, so the leaning to understanding how architecture works in creating a sense of place came very early—starting at 10 years old.

Let’s start by exploring the idea of definition.

Wikipedia offers:

Branded environments extend the experience of an organization or company’s brand, or distinguishing characteristics as expressed in names, symbols and designs, to the design of interior or exterior settings. Components of a branded environment can include finish materials, environmental graphics, way-finding devices and signage and identity systems. Creators of branded environments leverage the effect of the physical structure and organization of space to help deliver their clients’ identity attributes, personality and key messages.

The creation of branded environments grew out of a movement within the practice of interior design in the early 1990’s that recognized that brand equity, or the perceived value in the identifying brand characteristics of an organization, could be applied to three-dimensional environments.

The practice of designing branded environments is often a research-driven effort led by an interior designer or architect, and may include a multi-disciplinary team of strategic consultants, brand development experts, marketing and communications consultants, and graphic designers. Particularly effective for retail,[1] museum and exhibit design, branded environments can support the success of many organizational types, from corporate to institutional and educational. The designed environment can reflect or express the attributes of a community or the competitive advantages of a company’s product or service.

Benefits of a branded environment can include improved brand position and communication, better customer recognition, differentiation from competitors and higher perceived value from investors.[2] Internally, benefits may include higher employee satisfaction and retention, increased productivity, and better understanding of an organization’s mission, vision and values.

We believe that any brand, as a holistic enterprise, needs to offer coherent expression in built space. That sense of holism, component elements building to a whole — integrated experience — seems a natural proposition, yet interestingly enough, there are plenty of existing, long standing references that do not elicit a connection between brand thinking and built environment. These companies seem pretty smart — but there’s a big break between concept and ideation – and branded execution in space. These contrary edifices that suggest nothing of what goes on in the interiors.

IBM | Somers campus, NY

IBM | Somers campus, NY

Kraft | Northfield Campus, IL

Kraft | Northfield Campus, IL

Soulless, too. And, to these, and many others, I’ve been there.

It’s not worth exploring more — it’s pretty obvious that there’s a legacy of creating campuses or building expressions that don’t, really, communicate anything about the aesthetic of the brand. I can offer United Airlines (Oakbrook, IL); Kellogg’s (Minneapolis, MN); Hershey (Hershey, PA); Apple Computer, (Cupertino, CA);

Microsoft, (Redmond,WA) and countless others simply don’t say much of anything about brand vision. Sure, they’re pretty, but what’s the point? They’re largely containment devices. And I suppose that there’s something to that strategy — get ’em in there (and out of there) as quickly and as inexpensively as possible.

Whatever the scale of the brand — efforts should be made to create story in spatial experience. The added sensate brand management renderings of scent, sound, touch, taste — these are enriching attributes of enclosure and experience. They, too, are important.

But looking around, there is more to explore. How to tell a brand story dynamically in the context of space, place and presence — and I’m not talking about bold logo applications. For while this newly-evolved campus entry rendering of Google is interesting, I’m not sure really what is says about the brand. The juxtaposition of the draped-layering seems like confusion and distraction, rather than the heart of one of the most powerful search tools ever known. But there’s a statement to conceptualization.

But what about architecture telling the story—in conceptual application?

I’m looking for expansions on that statement, that grouping of ideas — how can they be best tied together. What’s the thread? And there have been other inquisitive references that I’ve examined on the alignment of these messages: space, place, story. From Starbucks to Gucci, and Tom Ford, from Apple Stores to Nordstrom brandcoding.

Can you, as a brand designer, integrate patterned storytelling and

design linguistics into the experience of your stores and their customers? The key is memorability—experiences that are so recognizable that guests simply can’t forget them. Like Nordstrom’s pin-striping language in LA.

I’m exploring this because I’m looking for answers—I was discussing this with architects, Dawn Clark and Tom Kundig. Who’s doing what to answer these questions — and who’s doing it right? We talked the drama of Oakley, their philosophy—and that, in a totally different modeling, yet still philosophically disposed, the visual brand of Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheum.

One study:

Oakley

“I always knew we would succeed. That comes from believing in what you’re doing, and striving to do it better than anyone thought possible.” Jim Jannard | Founder, Mad Scientist, Oakley

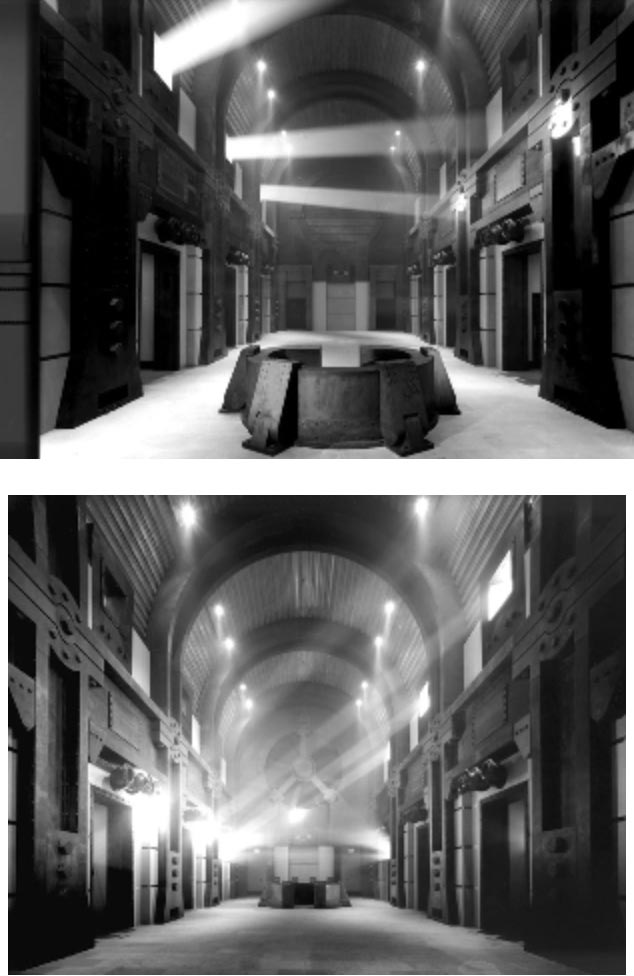

Oakley Interplanetary Headquarters

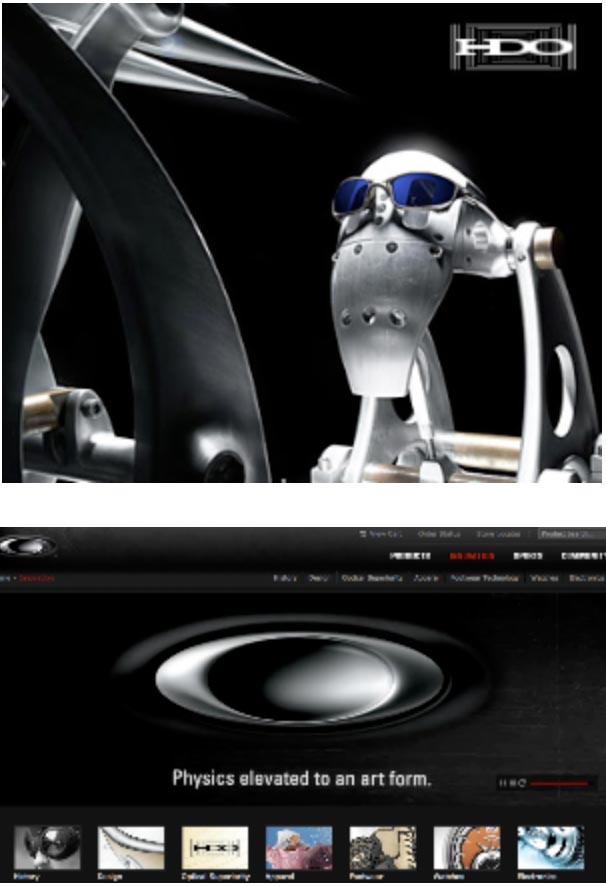

The building was designed by Colin Baden, president and chief creative officer of the company. Baden is, as well, one of the founding industrial designers for the company. Oakley was named for the dog of Jim Jannard, founder and chief executive officer. The symbology, the Oakley rendering, in the brand mark, is called the Icon. It’s the eye on everything.

And it, inherently, drives the spirit of everything that the company does—including the architecture, which is a kind of massive production design—it’s a theatrical set, a prop, for the brand. But think of prop as proposition—of attitude, ethos, invention and innovation. And while this might be seemingly excessive to many in the architectural community, it’s a prime example of principle driven by principal—Mr. Baden, who’s earned the moniker of the Mad Scientist, along with Jim Jannard, that together lead to the entry way—to another world.

The design thinking is pervasive—and the marketing strategy, even working to forming the design of the products, extends deeply into the culture. Even the stock-trading registration—the New York Stock Exchange: O O is the code. Eyes.

The design styling is surely fortress-like — and given the military nature of some of their product, it’s relevant: Oakley works with the U. S. military on both laser eye protection in assault eyewear and an alternative boot for the Elite Special Forces, in addition to the broad range of their consumer products.

The site entrance:

The space(s): It’s a place of reinforced blast walls, product torture chambers and the padded cells of mad science. Oakley’s design bunker is where inventions are conceived, developed, perfected and manufactured. In addition to the hidden catacombs of research labs and proving grounds, the architectural design of Oakley President Colin Baden includes a 400-seat amphitheater, and “absolutely no adult supervision.” Attitude, truth, invention, innovation.

They’re all part of the design code—and marketing brand strategy—of the group.

Tough, brutally tested, and designed in a brand place built to match.

These highly styled representations add to the sense of brand attitude:

Product visuals under “fire”:

More facts for reference:

Tim Yue | Parking medallion

• All design links back to brand story—the Oakley brandcode®.

• The 400,000 square foot building on a forty acre site was constructed by Snyder-Langston of Irvine, California—development, construction management and general contracting services.

• The facility includes office, manufacturing, assembly and distribution areas, as well as an Oakley museum, gift shops, and heliport.

• Employee amenities include a NBA regulation basketball court, fitness center, full service cafeteria and a 450 seat auditorium.

• The industrial lobby, shown in the interior views, 6,000 square feet and is capped by a forty foot high stainless steel cylindrical structure above the building’s entrance.

And yes, the fan works.

Explorations on Oakley culture.

“If you’re going to do something, be brave and jump in, but do something meaningful.”

Jim Jannard

(Colin Baden | design director—architect of the campus)

Founding principal: principles—

A mad scientist named Jim Jannard began questioning the limits of industry standards. “No one believed my ideas,” said Jim. “No one would listen.” In 1975, he went into business for himself. Jim started Oakley with $300 and the simple idea of making products that work better and look better than anything else out there.

In his garage lab, Jim developed a new kind of motorcycle handgrip with a unique tread and a shape that fit the rider’s closed hand. “Everything in the world can and will be made better,” Jim told skeptics, “The only questions are, ‘when and by whom?’” Top pros took notice of the new design and its Unobtainium® material that actually increased grip with sweat.

For Jim, that meant challenging the limits of conventional thinking. His homespun company was struggling yet his next invention would become a mainstay in MX racing for 17 years. Jim created the O Frame® goggle with a lens curved in the perfect arc of a cylinder. Pros like Mark Barnett, Marty Smith, Johnny O‘Mara and Jeff Ward championed its clarity and wide peripheral view.

Jim went back to his lab and started reinventing sunglasses for sports. Few believed it could be done successfully, and most thought the industry’s big companies could not be challenged. Jim used innovations from his previous inventions to create “Eyeshades®,” a design that began an evolution of eyewear from generic accessory to vital equipment.

The first world-class competitor to approach the company was Greg LeMond, who became a three-time winner of the Tour de France. Other pros like Scott Tinley, Mark Allen and Lance Armstrong demanded the performance and protection offered by Eyeshades®.

Decades of innovation brought new product technologies, blends of science and art that have been awarded more than 540 patents worldwide. Today, Jannard’s brand has become the mark of excellence and the solution to challenges facing those who cannot compromise on performance.

“Inventions wrapped in art. Oakley was founded on that idea, and it still defines us.” Jim Jannard

And what of Rudolf Steiner, a proverbial closer to this discussion?

Rudolf Steiner, a integrative philosopher of naturalism, gifting superior education to children, founder of the Waldorf Steiner systems of learning, designed this building as a statement to his philosophy—and, other discussion team members were struck by the similarity of intentions—artful depth in philosophy, a “brand,” and a statement to holistic actualization of experience expressions.

Four years in building, 1924-1928.

Wikipedia notes:

It represents a pioneering use of visible concrete in architecture and has been granted protected status as a Swiss national monument. Art critic Michael Brennan has called the building a “true masterpiece of 20th-century expressionist architecture.”

The present Goetheanum houses a 1000-seat auditorium, now the center of an active artistic community incorporating performances of its in-house theater and eurythmy troupes as well as visiting performers from around the world. Full remodelings of the central auditorium took place in the mid-1950s and again in the late 1990s. The stained glass windows in the present building date from Steiner’s time; the painted ceiling and sculptural columns are contemporary replications or reinterpretations of those in the First Goetheanum.

In a dedicated gallery, the building also houses a nine-meter-high wooden sculpture,

The Representative of Humanity, by Edith Maryon and Rudolf Steiner.

Architectural principles

Steiner’s architecture is characterized by a liberation from traditional architectural constraints, especially through the departure from the right-angle as a basis for the building plan. For the first Goetheanum he achieved this in wood by employing boat builders to construct its rounded forms; for the second Goetheanum by using concrete to achieve sculptural shapes on an architectural scale.[16] The use of concrete to achieve organically expressive forms was an innovation for the times; in both buildings, Steiner sought to create forms that were spiritually expressive.[17]

Steiner suggested that he had derived the sculptural forms of the first Goetheanum from spiritual inspirations.

Designed “brand”-places—

built on deeper premises of a integrated sense of belief, design thinking and outcomes.

Tim | GIRVIN | Strategic Brands

Projects in strategy | story | naming | messaging | print

identity | built environments | packaging

social media | websites | interactive

–––––––––––––––––––––––

Digital | Built environments by Osean | Theatrical Branding

Waves | Art | Talismanika™ | Oom Carpet Arts | Technology Branding | Destination Brands