Once you begin your walk into the working world of perfume,

you’ll find that there is a place for you.

There is a vale that holds scented secrets that are just for you, that just reach into your heart and the most profoundly happy memories of your life as a human, perpetually smelling — knowingly or unknowingly — every moment of your stride into the scent of being. A forest, for example, is the dense and powerful swirl of complex organic molecules of fragrance, whirling around you as you move deeper and deeper into the arboreal realm. You scent and the electrical response of your interpretation goes straight to the front of your brain.

Our experience of the forest, what we know of trees, their split wood, dusts and boughs, the seeping saps which lend themselves to the outcomes of their essences and their fragrances — these are deepened in the psychic state of experience — would this be fearful, contented, fascinated or engaged?

Every tree has its flavor — crack a bough and you can scent one from another — each, their own.

The conifers have their legacy, and the deciduous trees have their own vocabulary.

One is rough-legged, acidic, piney and sharp, while the deciduous are softer, rounder, mellower.

And that is where Birch Bark falls, rounder, softer and still: preservative.

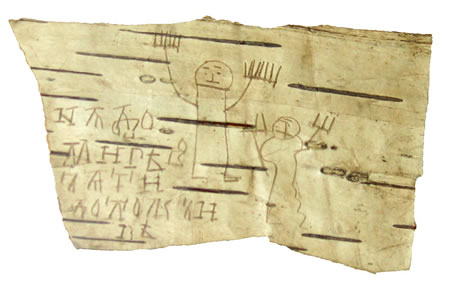

Birch bark lasts — not only as a distinctive essential oil, but also as long-lasting capable material – like something to preserve sacred texts. But, as we know, they are also used in common letter-writing, village documentation, children’s drawings, as well as czarist tractates during

their use in 9th-15th century Russia.

I’ve studied the history of writing in detail — from early metal manuscripts, to stone plates, to incised clay and finally, later: papyrus, vellum; and still later — the invention of paper. But one form can be found in tree skins — the bark of certain trees as a manuscript form.

In a foray a couple of years back, I learned more in a visit to the Early Buddhist Manuscripts Research Project in the palaeographic laboratories at the University of Washington.

Leaf Calligraphy | tsumaranimono

I’ve long drawn calligraphies on xylem, dried bark, pieces of wood, and carried secreted messages in curls of tree-skins, as a way of hidden messaging. Or, as in the above, the “bored little nothings” in Japanese, offered as simple gifts and mementos of encounters.

Birch bark and birch tar

Scent, script and scripture, story and history: mystery from the ancient forests.

How could these be possibly aligned? The story deepens still…

Sometime back, a couple of years ago, I was traveling in Firenze, with Dawn Clark. We were looking at perfume making, meeting with perfume makers and smelling scents. Meandering back into the recesses of the shelves of profumi, old shops, apothecaries and farmeceutica, expert noses and fragrance makers, we sample, scent and dream.

The idea of smelling “an object, an essential amalgam” is instantly evocative of place, it’s a leaping dreaming — smelling something, I sense: I scent; find place; speak memory; ignite idea, find voice, taste color and illuminate exposure. It just happens. I smell everything — sifting and sorting, scenting nearly everything that I touch, or come in contact with — it’s a perpetual curiosity.

“What’s that smell like?”

There are those that would say this is a fixation. But as a sensing component of how to live and be in the world, it’s one of the strongest, to experience holism.

Smell where you are.

Touring the shelves, of some out of the way Florentine scent shop, I’d found some obscure out-of-stock and remaindered scent, designed in Germany, made in Firenze, and I was knocked out — transfixed — by the flavor. Zibermann’s Golden Adler Eau de Parfum. It’s vanished from the market.

I was struck by the scent — but more so, what lay inside its layering.

There was something there. Deep inside that was darkly, yet magnetically attractive.

Standing there, with an accomplished perfume aesthete — he too was immediately struck by the inky wooden, burned character of the fragrance.

It was a dense, smoky tarred scent, with a hint of a kind of polished metal, slightly hardened — like a freshly sharpened axe. The combination was so surprising that it’s no wonder it disappeared instantly off the shelves and can be only found as remaindered items and as sampled fragrances.

And even now, these are gone.

That lead to a quest — one, reaching to the scenteur, Dr. James Dotson, that immediately recognized the smoky flavor of its exudation. Birch tar, he said. Generously, he sent along a small vial — and there it was. Laden with memories, dreams, visions, evocations.

Yet still, finding that fragrance, the sheer essence of birch tar, that’s something else — it’s not a common extraction. At least, not until you move in to learn more.

First, one might examine the tree — and a link, here.

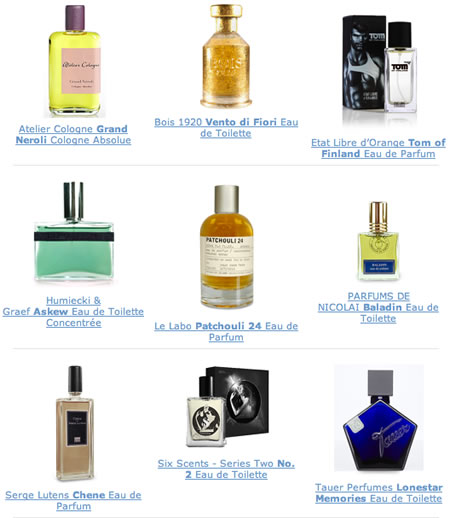

It turns out, in fact, that this distinctly dark, sexually complicating scent is an ancient one. One might find, as well — in even the opening research on birch tar — that there’s a potential for this being a hidden, dark and revealing note, in a number scents, though those shown below are less than commonly recognized, they are still built by esteemed noses. Scenting them, you’ll be drawn into a place that is reminiscent of another, older world.

Even Chanel has used the primordial scent of birch tar, recalling forest with distant pitch and wooded “burn” fragrances — a piece of charred wood, the pitch bubbled in the heat, captures something of this evocation. Russian leather, a classic foundational principle of masculine or hearty feminine scents has something of this notation — that leads to old libraries of rare books, saddlery, leather equipage that is well oiled and protected.

Scents of leather, birch and creosote:

www.luckyscent.com

A definition here, for Russian Leather, is “a smooth leather tanned with willow, birch, or oak, and scented on the flesh side with birch oil.” The ancient legacy of the drawn resin extends to the stone age, “Birch-tar was used widely as an adhesive as early as the late Paleolithic or early Mesolithic era. It has also been used as a disinfectant, in leather dressing, and in medicine.” And the method of its production is as “a substance (liquid when heated) derived from the dry distillation of the wood of the birch. It is therefore pyroligneous — compounded of guaiacol, phenols, cresol, xylenol, and creosol. These, to the fragrance aficionado offer further intimations — is there a familiarity, to guaiac, or creosol?

Guaiacol is present in wood smoke, resulting from the pyrolysis of lignin. The compound contributes to the flavor of many compounds, e.g. roasted coffee. Creosol is an ingredient of creosote. Compared with phenol, creosol is a less toxic disinfectant. But powerful indeed, an distant in history, their applications. Cresols have an odor characteristic to that of other simple phenols, reminiscent to some of a “coal tar” smell.

Hard to imagine, that these would have value — but I believe that the concept of smoke is something that is deeply rooted in the psychic scent / mnemonic space of people — those that can scent it, and distinguish it. There are numerous forums that wax eloquently over these fragrances. Dig into the Perfume Shrine, to explore more, of the leathers — and the inherent birched depth of their legacy here, the Vintage Perfume Vault.

The bridge, then to the other part of the story? It’s about the utility of birch — and the heritage going back thousands of years. To reference:

Medical Uses of Birch

The chaga mushroom is an adaptogen that grows on white birch trees, extracting the birch constituents and is used to treat cancer.

Birch bark is high in betulin and betulinic acid, phytochemicals which have potential as pharmaceuticals, and other chemicals which show promise as industrial lubricants.

Birch bark can be soaked until moist in water, and then formed into a cast for a broken arm.[7]

The inner bark of birch can be ingested safely.

In northern latitudes birch is considered to be the most important allergenic tree pollen, with an estimated 15-20% of hay fever sufferers sensitive to birch pollen grains.

Paper and the use of Birch Bark

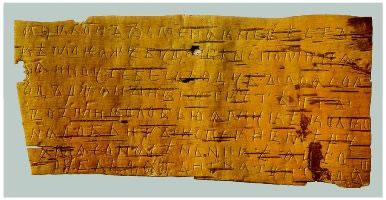

Birch bark document

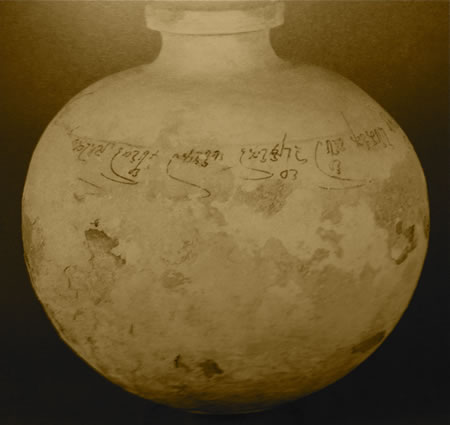

A birch bark inscription excavated from Novgorod, circa 1240–1260

Birch pulp’s short-fibres allow this hardwood to be used to make paper. In India, the birch (Sanskrit: bhurj) holds great historical significance in the culture of Northern India, where the thin bark coming off in winter was extensively used as writing paper. Birch paper (Sanskrit: bhurj p?tr?) is exceptionally durable and was the parchment used for many ancient Indian texts. This bark also has been used widely in ancient Russia as note paper (beresta) and for decorative purposes and even making footwear.

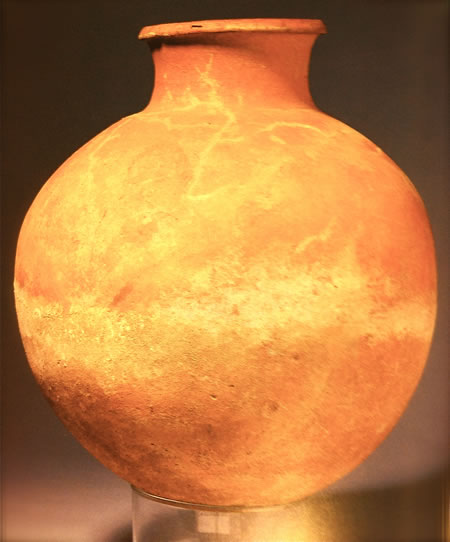

The clay pots, containing the manuscripts, with the Birch bark scriptures within, along with the rolled scrolls of bark shown above. (From Richard Salomon, The University of Washington Press)

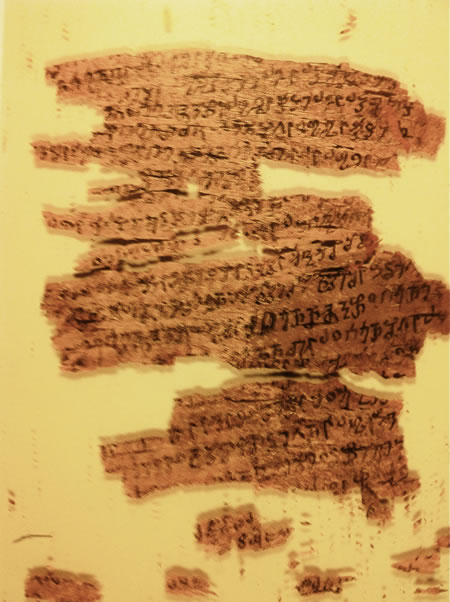

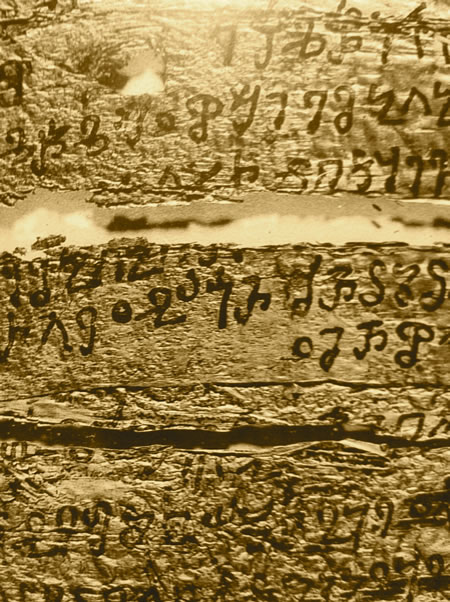

The Birch bark scriptures, in delicate reassembly and translation by Richard Salomon and Collen Cox. (From Richard Salomon, The University of Washington Press)

Therein, the bridge. Manuscripts, ancient Buddhist texts, scribed 2200 years ago — on birch bark. In meeting with scholars at the University of Washington, who are researching these fragments, found rolled, in urns, from the mountainous regions of Afghanistan, one of my questions was — “what do they smell like?” Of course, all of their studies were sealed in glass, the fragments are so profoundly delicate. They didn’t smell them, and both Richard Salomon and Collen Cox remarked — “is that even possible?” Of course, vials of fragrance have been recovered from ancient Egypt, still redolent of their unguent derivations. There’s more here to explore at their research website — they generously offered their time and exploration of their work over the course of the last 14 years.

According to AWOL — The Ancient World Online, this study, “the Early Buddhist Manuscripts Project was founded at the University of Washington in September 1996 to promote the study, edition and publication of twenty‐seven unique birch‐bark scrolls, written in the Kharo??hī script and the Gāndhārī language, that had been acquired by the British Library in 1994.

Further discoveries have greatly increased the number of known Gāndhārī manuscripts, and the EBMP is currently involved in the study of seventy‐six birch‐bark scrolls (primarily in the British Library, the Senior Collection, the University of Washington Libraries and the Library of Congress) as well as numerous smaller manuscript fragments (in the Schøyen Collection, the Hirayama Collection, the Hayashidera Collection and the Bibliothèque nationale de France). These manuscripts date from the first century BCE to the third century CE, and as such are the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts as well as the oldest manuscripts from South Asia. They provide unprecedented insights into the early history of Buddhism in South Asia as well as its transmission to Central Asia and China. The Gāndhārī Dictionary Project supports the work of the EBMP through its comprehensive database of Gāndhārī material (including inscriptions, administrative documents and coin legends in addition to the birch‐bark manuscripts) and by compiling the first dictionary and grammar of the Gāndhārī language. The research results of the EBMP and GDP and translations of the manuscripts are published by the University of Washington Press.”

The bridge: exploring scent, history, smoke and the mysterious intertwining of both, over time. I believe in the concept of collective, unconscious recognitions — and that the scent of smoke, whether arousing danger or comfort, can reach into the same vessel of archetypal memories in experience. Like the Native American legacy of the concept of story smoke, a mystical entwining of message, story, teachings and smoky prophecies, there are intermingling poetries that bind it all together.

t i m | GIRVINQUEENANNESTUDIOS

–––

EXPLORING THE FRAGRANCE OF SMOKE

https://www.girvin.com/?s=smoke