Or, how I’ve loved the Western Film — as a story concept — since I was a child.

A couple of weeks back, I went to see No Country for Old Men in NYC.

A.O. Scott reviewed it: http://nytimes.com/no-country

Josh Brolin as Llewelyn Moss

But whether he’d (A.O.Scott) played it down or up, I would have gone. I live on the edge of that genre. Mind. And otherwise. And with any new “western” release, I’m there.

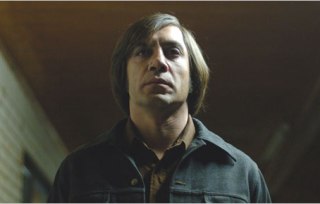

Javier Bardem as Anton Chigurh in “No Country for Old Men” Richard Foreman | Miramax

I go from Seattle to NYC, every other week — working at one office, then the other. And watching movies is a kind of creative exploration for me. And I mean that literally — watching them. Studying them. Sure, I like to be entertained, but I do savor — the examination and breaking apart of movies — the character of the film in its separate creative elements, and their holistic entirety.

It’s something that I do when I travel. I’ll go and see a movie at night, after work – oftentimes alone. I sit down in front. I’ve been exploring the idea of getting closer and closer to the screen. Why, that — why would you do that? For one, you can always find a seat. And then, two, there’s more of a creative positioning. It’s an exploration, but I’m increasingly interested in looking at the character of the film’s visuals, closer. I like to look at how a film is designed. For a long time, I’ve been a student of cinematic and theatrical production design. Sets.

And working on literally hundreds of films, as a designer for motion picture marketing, I need to know the story. And I’m not going there to exploring the specifics of storytelling and branding — I’ve written plenty about the exploration of the story, meaning and brand development. So, the lensed story and designing — I need to know what the film looks like. What’s the light and the quality of the illumination; what is and who did the set design, the placement of the story — its geography, what is the color, time period, stylistic references from that time; materials of the film, and how do people interact with them?

It’s all about that, in the set design, the illustrative framing — the story, and how the visuals and story intermingle, under direction, to be something captivating. Obviously, sometimes they are, other times not. But to do the work that I do, the more I know, the better job I can do in illustrating the story – and designing marketing materials and logos for a film.

What struck me about this film were two aspects of production and visualization. And, of course, the idea of it all comes from Cormac McCarthy’s original telling. I’d never heard of him, and read this story out of the blue, several years ago. What I found compelling in that writing was the actual style of how Cormac read the material — something like Charles Frazier (Cold Mountain) — accented; and the writing: it was like he’d invented a new form of language. Both of them, McCarthy and Frazier, have that quality. And that quality finds its way into the stark and heated visuals of the film and the production design, wavering in the mirage of intensity.

And when I read things, anything, my mind instantly translates all content to color visuals. If I read something before I go to bed, I’m certain that it will be reborn in dream material, often feeling cinematic in character.

The appropriateness of Joel and Ethan Coen directing and designing this filmed interpretation reaches back, really, to their first film — Blood Simple. That too, was a kind of redemptive “western” in a manner of speaking. But what I’m getting to here is a kind of continuing myth-making character that lies in the heart of the American western. It’s really the only place in the world for it, the American “West” — the only moments in history that align in just such a manner, to frame this kind of storytelling and experience — the quality of the western is archetypal. It’s heroically lonely, remote in its journey, profoundly personalized and reaching from (and into) the heart, the heat, the soul, the cold — to death. What my personal sense is, as a person that has corresponded with Joseph Campbell on mythmaking and a long running student of the Jungian archetype, is that the legendary character of the American West is representative of a endlessly fascinating mythic archetypal explication. Unfolded: the hero — begins the quest, lost, finds redemption — advances in completeness and, finally — tinged with the bittersweet. It’s the travail of being. It is the cycle of things that we call experience. And in a way, this reflective character applies and crosses the borders of humanity — from the sense of the native, to the interloper; and the intermingling of these spirits, for good or for bad. We have a dream, an exploration in living, we wander, we encounter breaks and fractures in our visioning experience, our lives are torn asunder — and, firmly, finally, staggered — we go forward.

Okay, it’s a generalization — but there are tints of truth there. Take any story of the American West, and there’s a quality of these mythic and epic characters that are magnetizing evidence of the classic, even Odyssean hero figures. The one that Joseph Campbell refers to as “The Hero of the Thousand Faces”. Perhaps unforgettable. What further evidence there might be can be found in the filmic intermixing of Akira Kurosawa, Sergio Leone…

(shown here in the visual dithered screen of For a Few Dollars More | Clint Eastwood | Warner Brothers)

Sam Peckinpah and Walter Hill — and now, perhaps, the slippery gestures of Quentin Tarantino — in mixing, if not mimicking, them all. And the Coen brothers.

The NYTimes references this in an article that brings to bear something else — in the mythological geography of the American Western — the sense of loneliness — the fight that will be either won or lost: alone. Or what they call — “a landscape of western battles both real and imagined” That surely does speak to Eastwood’s embodiment in the western spin of the Leone legacy. And it speaks to this, their reference to the character of Richard Misrach’s depictions:

Richard Misrach | fraenkel gallery, San Francisco

What is compelling, for me, about the intelligence of this overview, as well, is their use of Richard Misrach’s photographs as illustrations of that experience. I’d connected with Richard early on, in the 80s, working on his Graecism dye transfer portfolio. This boxed set came after his night dolmen, moonlight cairns, and then desert series – and my connection with him, working with him on the design of the folio, was precisely because of the power of that desert (and deserted) imagery — the potency of that landscape for me.

Richard Misrach | Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

If you’ve walked the desert — even at night — you’ll get the sense of how this quintessential visual links to the concept of the Western. And this comes clearly into play in the very beginning of the Coen’s rendering of No Country. And it happens repeatedly in the film — out there, the big sky, the stretches of no-thing, no-how, no-where, no-who. But there’s something there and it is menacing and approaching with deadly intention. It’s beautiful, but it will kill you, if you’re not paying attention.

So I grew up with this spellbinding fascination, as a kid. And there I was bitten by the rattlesnake, charmed — to find my self continuously drawn back to that character and that space of story. There were the TV shows: Branded, Rawhide, WagonTrain, Bonanza; then there were the movies — Stagecoach, as essential family fare; then the real stuff — High Noon; Gunfight at OK Corral; Fist Full of Dollars; 3.10 To Yuma, For a Few Dollars More; Shane; The Good, The Bad, The Ugly; The Wild Bunch, The Magnificent Seven… And what I found magnetizing to this last round — the Leone | Eastwood collaborations is that, somehow, the figuring of the story was not only western, but it was foreign — even a little scary.

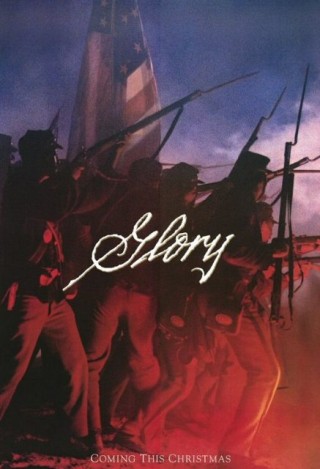

What I might offer, in the review of all of this for myself, what the western means in the structure of my story, is a kind of sequential and psychic welling for me. There’s a thematic percolation, that continues to bubble forth. It relates to my explorations as a designer — where I’ve been, and where it has taken me. So coming from this earlier childhood compulsion with virtually any western, to becoming involved with the motion picture industry in the 70s, and then developing a kind of sense and designerly direction that somehow tied me to these types of films — something appropriate to a sense of execution that tied me to their marketing. Here’s what I did, either in working with the studio, designing the treatments, or contributing to their direction — that limited litany is:

Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves

I worked on the prototypical flavoring of this identity treatment for Orion.

……..

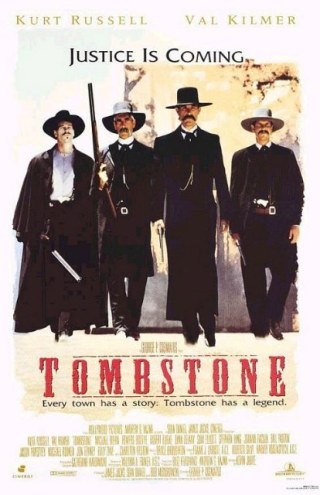

Tombstone for Disney — out of dozens of hand drawn and painted renderings of old shop lettering, victoriana and cowboy letterpress posters — this type treatment was chosen, along with a menacing lineup.

……..

A dream call from Warner Brothers creative handler, Joe Hyams lead to the development of the design treatments for Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. And my work there was a call from Clint about this new photograph, on set, with him and a massive revolver. “How about that, as a teaser with your logo?”

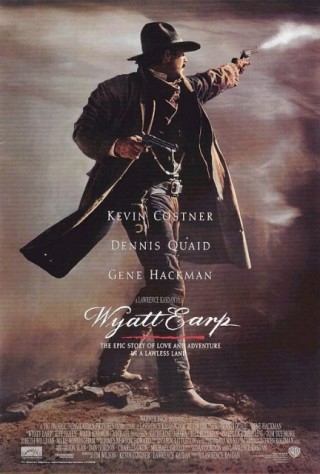

Kevin Costner’s call was that there was a gun found with his signature — that’s Wyatt Earp. “Can you duplicate that?”

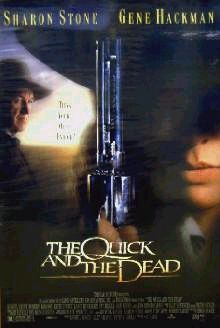

And there’s working for Sharon Stone — and The Quick and the Dead. Her call, from working with her on some other personal projects.

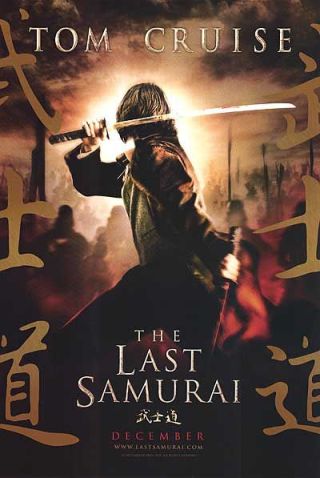

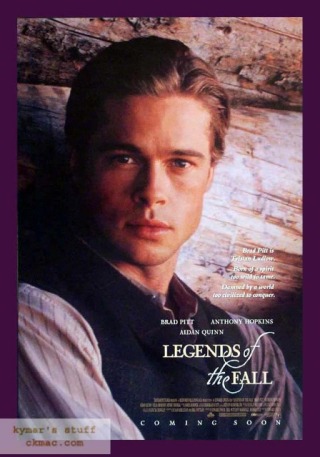

And, in a way, these spoke to the character of the west, and the western, in a different way — all three, from Edward Zwick’s directorial and producer roster. And in each, the styling of the identity of the film comes from my legacy of imagination — lingering, perhaps, in the dreams of the west…The Last Samurai — originally visualized as a customized classical roman, yet letterpress of the period font.

Any reflective writing is about reaching back into the character of the self, to find again what lies at the heart. Your heart is about where you’ve been. Being a creative, means that you are incessantly going back to the heart of things — your self, found anew, and remade.

Another story.

tsg | nyc

—-

Tim Girvin