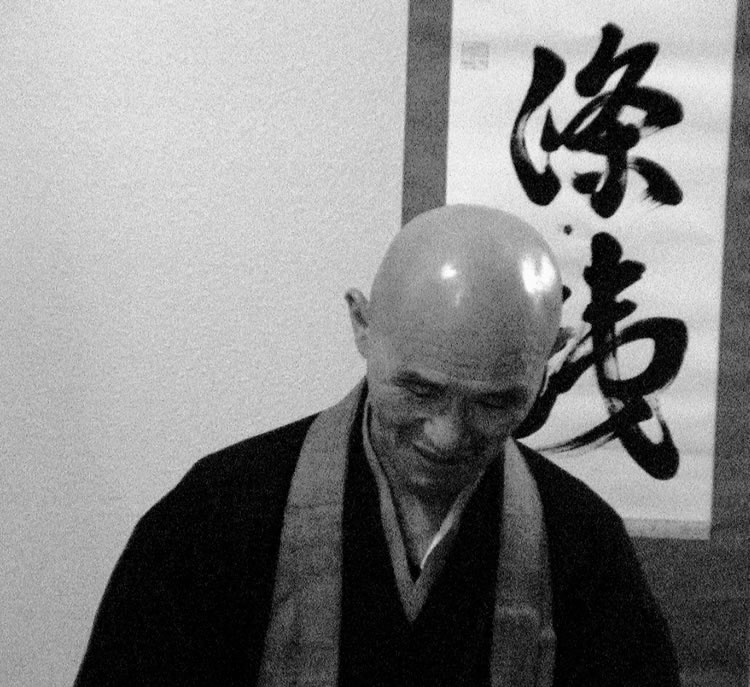

ROSHI HARADA SHODO

THE MOST IMPORTANT PART OF STORYTELLING IS LISTENING.

Sometime back, I drove up to Mukilteo, took the ferry across to Whidbey Island, and at 3.00pm had tea with the Zen Master, Sōgenji Abbot, Roshi Harada Shodo.

I had been introduced to him at a meditation session, master lesson and exhibition of his zen-ga, or Zen-based calligraphic treatments at his zendo, or training center in…a part of Seattle. His trademark, in a manner, is the circle brush-stroked drawing of the ensō — a quintessential Zen mystery mark — the openness of the now, the infinity of the future, the white sphere of containment, the black rough stroke of supreme centering. An overview, to reference.

An offering at the ensō, One Drop Zendo.

As the last part of his name implies, sho-do speaks of the “way” of writing. “Sho” is writing, “do” is way, in Japanese (Tao, the “way’ is in Chinese). Cha-do is, by the same linguistic measure, the way of tea.

Driving out on the sunlit marshes and pastureland to this farmhouse was a shocking, but alluring break, from the furious pace of the earlier day — kind of shattering, the shuttling in to slow down, way down, to meet and to listen to an Abbot of a monastery. I was stressing about getting there on time, to cadencing the ferry runs against my meeting with the Abbot of Sogenji — a monastery set in the rigor of Zen study and meditational training.

Sōgenji Monastery, Okayama, Japan [photography by Kenji Chida]

During that trip to both OneDropHospice an evolution of Sōgenji Monastery in Japan as well as their zendo — Meditation Center in the San Juan Islands — high, nimbus clouds burgeoned and bustled dark on the horizon, a brilliant blue sky shown through, contrasting the verdant greens of the farmlands and forests. I was exhausted — and stopped on the road to walk, settle in, embrace the colors, scents and countryside. The sea channel glimmered in the furthest plain, refracting the scintillate light from the sun. The air was fresh, windswept from the salt-spray of the waterside, lapping at the edge of the distant, sea-timbered shoreline.

Arriving at the farm rented by the school for the Zesshin, or meditation retreat, was appropriately simple and unpretentious. It was a ranch style, classically pitched roof farmhouse structure, stationed in the middle of a cordoned field; horses gathered in the distance. Peering into the main house, I observed the participants in zazen, the formal position of meditation of Zen Buddhism. All members were dressed in the formal garb of classical Japanese attire, sashed heavy grade woven cotton, carefully pleated and starched, lighter undergarments, kimono-like in form; this, a quirky mix in the very non-Asian field of architecture and surroundings. As I arrived, my contact came out — the ever-present Zen enthusiast and translator of the Roshi, Chi-san or Priscilla Storandt and happily greeted me and bade me entrance to another separate structure, the guesthouse, a smallish, discrete building located away from the main house.

Removing my shoes, I entered, still wearing my suit and overcoat, detailed with a pin, one of the eight Buddhist treasures, the eternal knot, designed silver. The space had the bitter scent of the green cha, a powerful, bright green, dense tea, smoky and strong, served in large, two hands-sized bowls, coupled with the faint wisp of woody incense, the delicate note one experiences in Buddhist temples in Japan.

I didn’t know what to say, let alone ask; I came in, sat down and we looked at each other.

It’s disarming to sit in the presence of a person that has dedicated the larger part of his life to deep meditation, practice of serious studies — memorized stanzas of mantras, litanies of spiritual figures, and continuous training — everyday, mostly beginning at 3.50am,

the morning bell of awakening.

But what struck me was his completely open demeanor – he leans in with a big smile beaming — like, “what’s next?”

“So, what about it?” That question came to me — more as a general query — okay, “now what?”

He has a questioning expression, as if he is constantly smitten with curiosity. His face, with its marvelous sense of openness, looks ready to laugh, and when he exclaims, his smile cracks wide in a facial gesture of complete, joyful hilarity. He is lean and looks like he laughs a lot. Roshi was sitting on the pad commonly used in meditation; his ineffable translator sat nearby. After the typical introductions and felicitations in Japanese, we sat and passed the time. The talk in the beginning was casual, friendly, exchanging the usual pleasantries that are the frequent opening discourse in Japanese.

He said, since I was wearing this Buddhist knot on my outer lapel, was I familiar with Buddhism, perhaps a practicing Buddhist student? Did I have any questions about Zen? I asked some questions.

How did I learn about Zen? I spoke of my introduction to Zen (to his inquiry) some 25 years ago, when I first read “Zen and Japanese Culture” by the great American Roshi, Daisetz Suzuki, who a half century earlier had brought the first simple teaching of Zen (or in the Chinese: Chan) Buddhism to the U.S. I indicated that my experience with this cultural expression and form of worship was electrified by the connection between the simple, shibui spirit of Zen and its visual outcomes in gardens, temple compounds, stone arrangements, sand oceans, calligraphy and painting, food, flower arrangement, swordplay and sword making, archery and sculpture. I said that I was still perhaps too preoccupied with the outcomes-towards-the outside-and less focused on the inner spirit of Zen. I understood and knew it, but I couldn’t be it.

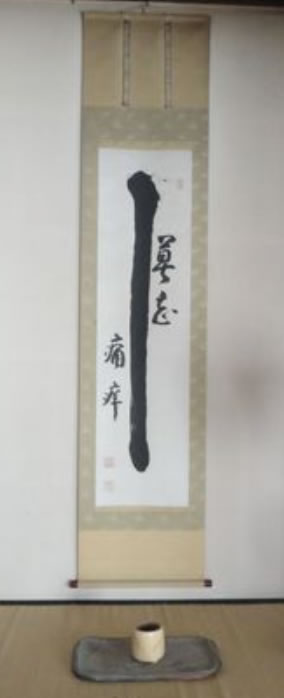

He said: “Sometimes you have to walk around the garden, maybe to be on the outside, outside of the fence, to begin to see what is inside. To take the first step to the inside, you must start on the outside.” He then gave me a piece of calligraphy, “Bamboo has joints, above and below”, which he had inscribed. What does that mean? I don’t know. (image attached) It has a tall vertical stroke, which has the feeling of a powerful piece of bamboo. Bamboo has a special place for me, as you might know, from the arrangements in the lobby, telling our story and working methods. I explained how, when I was younger, I introduced a toddler child to bamboo, all the different types, and how it grows. How it mysteriously comes out of the ground in one form, then turns into another. It is supple, yet strong. This child called me “bamboo” for years (now he’s graduated from college in LA). He asked if I had any examples of my work, since this was part of my introduction to him.

I told him that I had always been fascinated by the energy of Chinese/Japanese calligraphy and painting and that, with the Zen book I mentioned, how this had influenced my work. “Energy is eternal delight”, said William Blake, and for me, this is the potency of this form of calligraphy and drawing, it speaks of capturing the energy of the thing said, the spirit of the object to be illustrated; its ch’i; its energy and vitality — the dynamic rhythm, life-force and breath are expressed in gesture. [Chinese, ch’i, below.]

I gave him a tsumaranai-mono (“a boring little nothing”), a keepsake book of cards of the Girvin 20th Anniversary cards. He went through them carefully. And said, in Japanese: “So, I see”.

He asked what kind of work was I doing in Japan, and what is this thing called “branding”? He was given one of GIRVIN articles as part of the introduction. I explained that, as in Japan, marks and symbols for a company, or in the specific Japanese instance, a family crest, “speak to the spirit, the driving flame of that entity. Branding is about finding the flame, and keeping it lit. This is what we do. Here in the US, and in his homeland.” He said that in Japan, “sometimes the wrapping is so beautiful on the outside, you keep unwrapping layer upon wonderful layer, and then, when you get to the center, there is nothing”. I asked, “is Zen in the center, or the outside?”

“It’s neither, it’s both” — he replied.

I acknowledged that perhaps a lot of what our profession did was on the outside, but that the important essence was on the inside. I noted that I spent a lot of time working with my clients on remembering the inside before doing any work on the outside. We tried to understand this first, internal essence, then work outwardly.

Start in, go out.

This inquiry led to the obvious overview, that sometimes you are on the outside, with the fancy dressing and “packaging”, but it is what is held in the interior that is most important.

“What’s inside is what people will remember, not the superficiality of the outside.”

“Yes,” I mentioned, “Sure — a striking image could be one way of reaching people’s attention, but the attentive memorability of a lifetime comes from the inside. That is what is remembered.”

He offered more. “All of us are progressively unwrapping, to get to the center, slowly, or in some instances, quickly.

I think about this inside and outside all the time. What is outwardly obvious, and what would be likely more concealed on the inside – the hidden state of things, the other side.

We talked about this in the context of calligraphy — the stroke that is there, made in ink, and the stroke of white paper, that is left untouched — and the balance of the story that it tells.

“This was an interesting experience, of the interior and the exterior, and certainly something that has been part of my exploratory all of these years. Looking into the garden, to the beauty of the inside arrangements, stones, grasses, pebbles, exquisite in their simplicity, yet surrounded by the containment of the outside, perhaps also beautiful expressions of the “soul” that lies inside. The Roshi said: “They both have their value, their place. It all depends on where you are, on the path,”

With that, one hour later, I left. He went into dinner. And more practice.

I drove down the spine of the island, then across the ferry-run, then home, thinking — what is the point of worrying about the outside, if you’re not thinking about the inside? And what’s the point of thinking about the inside, of you don’t care about the outside?

As in the stroke — yes, you draw the black, but it’s the white

that remains in making the point of the entire gesture.

This calligraphy of Yamada Mumon Roshi hangs in the Tokonomo of the sanzen room at Sogenji.

It says:

“don’t forget the pain.”

Tim | LOS ANGELES INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

B R A N D M Y S T I C I S M | Deep Journeys to Team & Enterprise

D i s c o v e r y: http://goo.gl/DNfwS9

HUMANS, BRANDING + H E A R T

GIRVIN BrandJourneys®

http://goo.gl/iyQIzK

And sometimes the outside is a true of reflection of the inside a mirror of the the soul without frills.

Another great piece. Thanks for sharing.

Z