Designing experiences and retail strategy | enlightening presence in the power of feminine visionaries.

Right now, Girvin, the firm, is comprised mostly of women. And over time, I’ve found that women, as team partners, are superlative creative resources. And, from 35 years of client perspectives, there are many long-running relationships that are based on feminine leadership — from CEOs, CMOs, COOs — in technology, product development, brand managers, interactive leaders, marketing, brand strategists, packaging mavens and start-ups to brands that are dozens, if not hundreds, of years old.

Any examination of the most powerful leadership in the world invariably culls a potent cadre of women that drive decisions at the top, listed here.

But this proposition is about two women that I’ve met, that have lead extraordinary living, life-long campaigns as retail visionaries. And surely there are more — but this is personal, and that’s a guiding rule for more of what I’ve done — it’s all personal.

Work, for me, starting in the 70s, in NYC, was about embracing the city and the creativity that resounded there. And I was an inveterate stalker of the cool back then, as now. But I was most particularly interested in the people –themselves — and less so the businesses that they represented. I tried to connect with the leadership of the brands that I found the most compelling. And the people that were in the news. To learn about what was happening, more than 30 years ago in NYC, I subscribed to W | WWD, Interview and to New York Magazine. I also subscribed to the various international design, retail, interiors and architectural magazines. That might’ve been the real nexus — the curiosity seeking — for seeing what was going on.

And if there was someone incredible, simply — I’d pursue them. Men, or women — I’d seek them out; or they would come to me, by good fortune. So that might’ve been luminaries like Jorge Luis Borges, Milton Glaser, Herb Lubalin, Philip Glass, Jack Lenor Larsen, Diane Von Furstenberg, Cathy Hardwick, Joseph Montebello, Massimo and Lella Vignelli, Antonio Lopez, John Jay, Nob+Non Utsumi, Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Harry Partch — others. For me, it’s about the reach to the person — and my legacy is about doing just that; explore your curiosity, find someone that you’re interested in, and go and talk to them.

Being in that swing, that circuit of exploration, I met — back then, Geraldine Stutz. The opening connection there was Bobbie Currie, who was a window dresser extraordinaire, back in the old days (the 70s). Then from there, meeting him — he was an itinerant consultant of the hippest of the hip window installations — I met Geri Stutz. Watching him work, at night, on an installation at Bendel’s — Stutz came by to see what was happening, or better still, really, was working late as well and the alignment occurred.

What sequencing then? “What I like about your store, is that it’s kind like a village” — to GS’s retort: “and that’s the point of it, that it’s supposed to be intimate, that it is a series of shops, in shops — the store is a bigger experience, but it works because it’s many smaller shops, that create a kind of shopping village — a street of them. And I can change them — ones that work, stay; and ones that don’t work, go. And of course, Robert’s work celebrates them all — creating the kind of drama that brings people into the store in the first place.” I can recall that phrasing, for me, being a profound conversation — that moment, that idea. That it’s not the story of the store, that the very story is the store is many stories — it’s not just one big monolithic enterprise, but rather is many individuated expressions.

It’s hard to find more on her, as remarkable as she was — I’m sure there’s more out there, in terms of her presence, offerings, history, but even wikis are scant: “Geraldine Stutz (August 5, 1924 – April 8, 2005) was an American retail groundbreaker. She was president of Henri Bendel for 29 years. Born in Chicago, Illinois, she began her career as a shoe editor at Glamour. Her name first became really known when she was Vice President of I. Miller Shoes in the 1950s where she helped launch Andy Warhol. From there she was selected to head Henri Bendel.”

She introduced the famous “Street of Shops”, the boutiques-within-a-specialty-store concept which later gained wide popularity at the store’s former location on 57th Street in New York City. The Bendel retail empire is presently owned by Limited Brands based in Columbus. And up to that time, before the acquisition — the personality most associated with the store was Stutz, the HB president for twenty-nine years until 1986 when the store was sold. Given some earlier notations on the Limited, and the characterization of that founder, Leslie Wexner, his meditations on merchandising and sales, it’s no wonder the store was an attractive target.

Wilbur Pippin (NYTimes)

Stutz was once asked: “What is the difference between mere fashion and true style?”

Her answer was: “Fashion says ‘Me too’, and style says ‘Only me’.”

There is a link, to the love of shoes, in Stutz’s background and the Belgian legacy of shoemaking, and the founding family of Henri Bendel. Colleagues described Ms. Stutz as an industrious learner who immersed herself in the subject matter. Grace Mirabella, the former editor of Mirabella magazine, recalled an introduction to Ms. Stutz in the early 1950’s, when Ms. Mirabella was working at Vogue. “She loved to talk about the business and what was going on behind the scenes, and she knew everything about shoes,” Ms. Mirabella said, according to obituary notes in the New York Times.

Ms. Stutz put her knowledge to practical use when she went to work for several footwear manufacturers, including I. Miller, the company for which Andy Warhol designed advertisements, after it was sold to the conglomerate Genesco.

Indeed, one of the scions of the Bendel group only just passed away (well, about a decade ago) — “Henri Bendel, the founder of Belgian Shoes and a former president of the fabled Manhattan specialty store founded by his uncle in 1909, died at his home in Manhattan. He was 89.

As the store leader — before Geri Stutz — Bendel assumed the presidency of the store in 1935 after the death of his uncle, for whom he was named, and he retired in 1954 when the family sold it. Mr. Bendel, who had worked closely with several Belgian shoe-making families during the 19 years he served as president of Henri Bendel Inc., purchased two 300-year-old shoe manufacturing companies in Belgium in 1956 and began producing a casual, classic loafer that became a staple of New York fashion.

The hand-tailored, slipper-soft shoes, made for both men and women, come in many colors and materials, and are trimmed with a signature bow readily recognized by fashion connoisseurs — and that design link came to be known as the bridge for Geraldine Stutz’s move into the leadership at the helm of Bendel’s. Some of this stylish grouping of shoes are regarded as collectibles and are still widely copied by other designers.

The Henri Bendel store was for decades a prestigious outlet for such haute couture fashion houses as Chanel, Dior and Balenciaga. It was sold by the Bendel family in 1954 to a group of investors — and it was at this juncture that Ms. Stutz took control of creative leadership. And it was the evocation of invention, guts and risk-taking that allowed her to flourish — a legendary eye for discovering the newest designers and using them first, installing their collections in elaborately merchandised departments that heralded the introduction of a new generation of fashion stars – Stephen Burrows, Perry Ellis, Jean Muir, Sonia Rykiel, Carlos Falchi, Mary McFadden, Holly Harp and Ralph Lauren among them.

In a commentary from the founding leadership, Maxey Jarman, its president, recognized in Ms. Stutz an ability for merchandising and advertising, and named her to run the Henri Bendel store in 1957. “Jarman had talked to her at great length about her vision for the store,” Ms. Rosenberg said. “It was not going to be a store for everybody.”

Henri Bendel’s had different, emerging visions — it was known, during its evolution, at various times as a hat shop and as the source of the Duke of Windsor’s wardrobe. Ms. Stutz’s concept was narrowly focused on a young, sophisticated urban woman, and she rarely ordered clothes larger than size 10. According to references in the New York Times, in an article in New York magazine in 1987, Ms. Stutz described her taste for what she called “dog whistle” fashion: “clothes with a pitch so high and special that only the thinnest and most sophisticated women would hear their call.” And in the modeling of diversity in application, she was also one of the first retailers to consider merchandising food and furniture alongside fashion, and she made way for the in-store designer boutique in the late 1960’s, as she did for Ms. Rykiel.

Joan Kaner, the fashion director of Neiman Marcus offered, “she recognized that fashion was more than just about clothing; it was about lifestyle and how one lives.” Kaner worked under Ms. Stutz from 1967 to 1976. “She thought to put in perfumed candles and potpourri at the entrances so that when people walked in, they got this wonderful aroma. She was born with impeccable taste, and practically brought over every European designer who ever came to America.” That idea of creating sensation — of reaching to the senses of experience was a telltale mark of retail genius — far in advance of many other store models of presentation and holistic framing of telling complete, sensate stories.

Stutz’s “Street of Shops” vanquished what was formerly a dimly lit floor with merchandise randomly displayed along a 100-foot corridor. She upgraded the materials, installing marble floors and boutiques, small shops within the larger store that changed seasonally evolved, stocked with exclusive merchandise culled from markets around the world – a flower shop, stationery, a tiny art gallery, tabletop items from Frank MacIntosh, Lee Bailey’s home displays, and a boutique called “Port of Call” with objects from Vietnam and Thailand.

Ms. Rosenberg recalled her travel to Paris exploring the new market for ready-to-wear in 1959, when Ms. Stutz told her, “Buy anything you want.”

Grace Mirabella remembered that “It was a store that was edited like a magazine. It was everybody’s meeting place on Saturdays or at Christmastime.”

Ms. Stutz took the in-store-shop concept further in the late 1960’s with boutiques dedicated to the collections of designers she felt could succeed with the store’s support. Stephen Burrows opened his boutique there in 1969, an experience he recalled as a defining moment of his career (one he replicated in 2002 at Bendel’s current site: 712 Fifth Avenue). Others found their start there as well — Robert Rufino, the vice president of creative services at Tiffany & Co., is one of the many retail executives who found career initiations and inspirations with Ms. Stutz. He designed windows for the company in the 1970’s, and recalled Ms. Stutz’s ability to intermingle her acquisitive fascination with art, film infused with fashion.

Rufino offered: “In those days, there was nothing else like Henri Bendel. It was like working for the best house in the world. To take this little town house and make it look like someone lived there, as you were going from room to room – it was just one woman’s vision on the world of fashion, and yet it did incredibly well.”

Furthering her sense of stylistic leadership — and ownership, in 1980, Ms. Stutz assembled a team of investors and acquired the store from Genesco. Five years later she sold her interest, and worked as a publisher with Random House, overseeing books on Andy Warhol and Elsie de Wolfe. She also continued to consult with designers and retailers through a practice called GSG Group, which she founded in 1993.

Many longtime Bendel shoppers recall Ms. Stutz’s 1958 overhaul of the main floor at the store, at 10 West 57th Street, into a U-shaped “Street of Shops” widely acknowledged as a precursor to modern shop-in-shop merchandising displays. Based on her taste alone, Ms. Stutz divided merchandise into small vitrines of watches, handbags, stockings, and along one side, an inspiring “Gilded Cage,” a giant replica of a birdcage that housed the cosmetics department.

“Geraldine had a vision of the kind of store she wanted to create,” said Jean Rosenberg, who was the vice president and merchandising director at Bendel’s from six months before Ms. Stutz’s arrival in 1957 to their joint departure in 1986, after the store was sold to The Limited. “It was for a particular kind of New York woman, where she could find a uniformity of taste and a certain amount of comfort in a smallish environment, where everything in one store was to her liking.”

What I’d offer to the concept of captivation — the attraction of the feminine in retail leadership — is intuition and guts. Gladwell references the concept of the most powerful insights in the moment of instinct — literally, the blink — the instinctual reaction of the moment. Stutz had the ability to do just that — react and buy, then tell the story and sell.

The concept of fashion leadership, in many instances directed by women, is hardly an unknown presumption — a recent article in the NYTimes explores this theme as a kind of disappearing trend — that even the concept of the fashion director — let alone the female CEO is a evanescent transition. Meeting with Dawn Mello, recently — and she declined to be formally “interviewed” –she talked about the uncertainty of the market and what that means for survival. Who, indeed, will survive? And what must they do, to survive?

Caution, the careful holding of watchful vigils on the market, the trends, and the reserves of the store — and, to reflection, how to hold onto the customer relationships. The most crucial asset of any store are the relationships — the customers whose connection to the store and the sellers within, the products being sold, and the implications of trust — they’re all critical to survival. What’s the relationship (or for me, what’s the story?) and who’s holding the flame to keep that burning bright?

According to the NYTimes interview with her, on the nature of fashion, design, leadership and buying insight — there’s a mirrored concern about permanence: “These people must be plenty nervous, they must all wonder, ‘Am I next?’ ”

And that concept of buying insights, understanding in advance, the trends and exploring the risk of the trading on the marketing presumptions of the readiness of the market is shown “Historically, fashion directors played a decisive role, influencing the look of the windows, floor displays and advertising. They made buying decisions, though they stopped short of writing the actual orders. Another vital part of the job was to scour the marketplace for trends and emerging talent that could create an exclusive image for the store.” Dawn Mello, in our conversations, referenced Robert Burke.

He suggests, as a successor to Mello’s leadership at Bergdorf, “The fashion director took a position,” the positioning of the role was about being a kind of aesthetic fulcrum, that person “had the idea, sourced it, manufactured it, figured out how to promote it, how to extend its life,” according to Burke — and, to the inverse: “Then he figured out what to do with it, in case it didn’t work.”

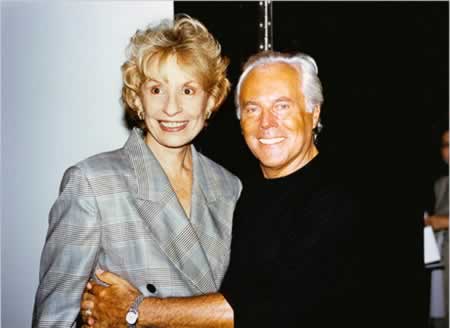

From the collection of Dawn Mello | Giorgio Armani

Dawn Mello, what’s her history? There’s a telling here, Dawn’s reference to interviewer Ruth La Ferla: “Mello ‘wielded the power to snap up designers like Donna Karan, Giorgio Armani and Michael Kors at the start of their careers. ‘To me that was it, to be the first kid on the block with a new talent or idea,’ she said.”

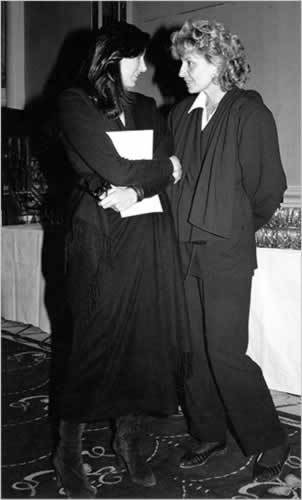

From the collection of Dawn Mello | Donna Karan

To ferret out designers who would be exclusive to the store, she found herself in the early ’80s sprinting across the street to a neighboring specialty store, where she accosted a young window dresser. “He was wearing a great-looking outfit,” she recalled, “so I said, ‘Gee, can who tell me who designed this?’ ” Impressed to learn that he was the designer, she invited him to see her.

Days later, he arrived at her office with his mother in tow, and an armful of clothes. “We gave him a little space in the store,” Ms. Mello said, “and that was the beginning of Michael Kors.”

Great story — and surely her storytelling is really about her ever increasing accuracy of insight and fashion perception; I spoke to her of the WWD on her desk — and she proffered, every day, “it’s my bible”; it’s the way to see into the business, instantaneously, incessantly honing her perspectives.

Reaching to her past, the history moves as a river of exploration and deepening experience, according to the School of Fashion Design curriculum vitae — “Dawn Mello was raised and educated in Lynn, Massachusetts. Her retail career includes B. Altman & Co, New York, where she was Director of Fashion Merchandising and The May Department Stores, Inc., where, during a period of eleven years, she held a series of positions, ultimately being promoted to Vice President and General Merchandise Manager.

Her career at Bergdorf Goodman began in 1975 when she joined the store as Vice President and Fashion Director. In 1980, she was promoted to Executive Vice President, responsible for the fashion, image and merchandising direction of the store. She was named President in 1983 of this famous New York fashion icon.

In 1989, Ms. Mello joined the Gucci Group as Executive Vice President and Creative Director Worldwide. She was based in Milan and was responsible for repositioning the Gucci image as a luxury brand. Dawn made “Gucci” a household word and one of the best known luxury brands on earth. But what about Gucci? Founded in 1921, by Guccio Gucci, it became an enterprise of extraordinary power — then collapsed, with spectacularly flammable family squabbles, then — with Dawn’s help — reascended — to the tune of $8.2 billion worldwide revenue last year (2008).

Maurizio Gucci, the grandson of founder Gucci, the emerging leader and the intellectually talented son of the clan, sought to bury the fighting that had torn the company and his family apart and turned to talent outside of the company for Gucci’s future. A turnaround of the company devised in the late 1980s made Gucci one of the world’s most influential fashion houses and a highly profitable business operation. And it was in 1989, that Maurizio managed to persuade Dawn Mello, whose revival of New York’s Bergdorf Goodman in the 1970s made her a star in the retail business, to join the newly formed Gucci Group as Executive Vice President and Creative Director Worldwid

At the helm of Gucci America was Domenico De Sole (above right), a former lawyer who helped oversee Maurizio’s takeover of ten 1987 and 1989. The last addition to the creative team, which already included designers from Geoffrey Beene and Calvin Klein, was a young designer named Tom Ford. Raised in Texas and New Mexico, he had been interested in fashion since his early teens but only decided to pursue a career as a designer after dropping out of Parsons School of Design in 1986 as an architecture major. Dawn Mello hired Ford in 1990 at the urging of his partner, writer and editor Richard Buckley.

Five years later, the person that drew Mello to Gucci, Maurizio Gucci, was murdered — even now, there are swirls of mystery surrounding the real story.

And just before that event, in 1994, Dawn Mello rejoined Bergdorf Goodman as President, with the merchandising organization reporting to her as well as fashion and all the creative aspects of marketing.

In 1999 she stared her own consulting company, Dawn Mello & Associates LLC, specializing in the luxury market. Based in New York, the firm maintains an international client list, from both retail and manufacturing industries. As well, according to a PR release from the South African luxury group, Richemont — after this venture, in 2007, she established another consulting partnership; Marty Wikstrom and Mello have joined forces to create an investment fund, called The Atelier Fund, whose principal investor is Richemont. Retail industry veterans – and friends – Mello and Wikstrom are working alongside Jon Brilliant, a former financial strategist at Harrods, and former managing director for U.S. operations at Syntek Capital AG, the Munich-based private equity fund. Wikstrom and Mello said the aim is to apply their decades of retail experience to building up affordable luxury fashion brands.

“We’re retailers – we have a sense of what works on the selling floor. We’re not your average private equity investors,” said Mello.

To further the impressions of her background, Dawn Mello has been honored for her outstanding achievement in her field by the Council of Fashion Designers of America and the New York Fashion Group as an outstanding woman in the retail industry. She is a recipient of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund’s award honoring individuals and corporate leaders dedicated to full equality for women. And in 2001 she was the first recipient of the Eleanor Lambert award named for the legendary fashion authority; the signification was given to Dawn Mello by the Council of Fashion Designers for her contribution to the culture of American fashion.

I believe in the power of the feminine – the instinctual insight of mature sensing of the nature of retail, which, to my thinking, is always about the familial (brand culture) and the intimacies of selling. Selling, successfully, is sharing — it is nurturing the burgeoning “love” of an object of commerce. The culture of a retail communion is a gathering of like-minded and committed people that reach into the heart of the product, and the experience, the sharing of it, in a manner that is convincing and hopefully genuine. Connecting. Attached. Engaged — it’s a story that is embraceable. And the feminine principle resides in that place of warming connectivity — it nurtures culture, humanity and the giving gesture of sharing…

My take on that front. Yours?

dawn