This is the third in a series on Human Brand | defining the inextricable link between people, founding vision and the brands that they produce.

“Respect your efforts, respect yourself. Self-respect leads to self-discipline. When you have both firmly under your belt, that’s real power.”

Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood is just a little younger than my father. And, in a way, I might compare the two of them, in terms of their potent stamina for living. Of course, the relationship that I have with my father is surely different than the connections that I’ve had with Clint Eastwood, working on his films. I was prepping for this addition to this series when I encountered this line review, from Variety.

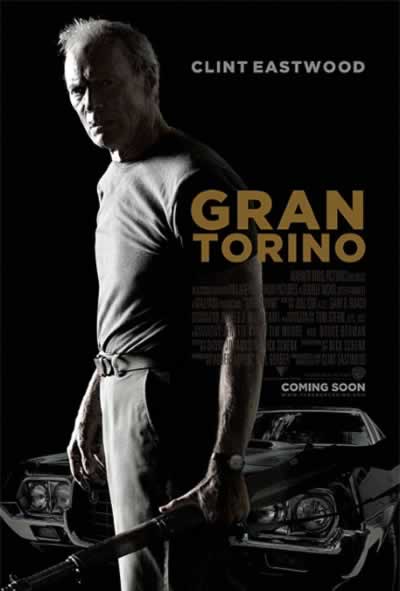

“At 78, perhaps the only actor in the history of American cinema to convincingly kick the butt of a guy 60 years his junior, the hard-headed, snarly mouthed Clint Eastwood of the 1970s comes growling back to life in “Gran Torino.” Centered on a cantankerous curmudgeon who can fairly be described as Archie Bunker fully loaded (with beer and guns), the actor-director’s second release of the season is his most stripped-down, unadorned picture in many a year, even as it continues his long preoccupation with race in American society. Highlighted by the star’s vastly entertaining performance, this funny, broad but ultimately serious-minded drama about an old-timer driven to put things right in his deteriorating neighborhood looks to be a big audience-pleaser with mainstream viewers of all ages.

“In his first screen appearance since 2004’s “Million Dollar Baby,” Eastwood revives memories of some of his earlier working-class characters; Korean War vet Walt Kowalski suggests a version of what Dirty Harry might have been like at this age, and there are elements as well of the narrow-minded, authority-driven figures in “The Gauntlet” and “Heartbreak Ridge,” as well as those films’ humble settings and plain aesthetics.”

But, in keeping with the series on Human Brands, I’ll stick to one side of the story.

I first connected with Clint, literally, after writing to him. And it’s interesting in this time of a rather complete disconnection from the concept of writing virtually anything by hand — like this blog — that the opening connection happened in a manner that was hand to hand. That is, in writing to him for an introduction, the effort was an introduction. “Here’s who I am, and here’s what I do.” Work, by hand. I believe in the hand, and the character of the work that comes from it.

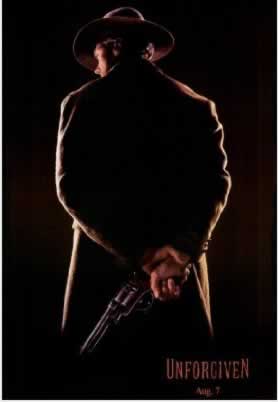

My opening link was with Joe Hyams, then a kind of handler for Clint — and it was an initial link into connecting with him directly, while he was on set, shooting in British Columbia. I can distinctly remember the page in my office in Seattle: “Tim, Clint Eastwood’s on the phone for you!” And there he was, speaking in his quiet, rough-sounding, coarse gravel of a voice. “I’m working on this film, that’s a western, which is something that I’ve not done in a long time. Actually, I never thought I’d do a western again. But I’m looking for something in the way of a logo for this film that’s going to get to the heart of what the story is — redemption. The story is about a man that’s given up on the world, life has dealt him a difficult hand; and cruelty is his response, rendered in a heartless manner; and he’s forced, by circumstance, to come back into the world to redeem himself.” I was shocked to actually hear his voice. But, after that, it turned into a kind of exchange, a conversation. We talked about styles, methods of illustrating the ideas, and then I worked on creating solutions to ship to him out in the wilds of British Columbia. I did, and we talked again. “I like all of them, but this is the one that I like the most….”

This treatment was drawn with a steel pen, broad-edged, on handmade paper. And the spirit of the rendering was about anguish, pain and forceful power, in emotion. As well, it evinced another character, which was the quality of typographic design — letter-pressed, or sign-writing from the late 1800s, in a kind of Victorian, hand-gestured styling.

Like this:

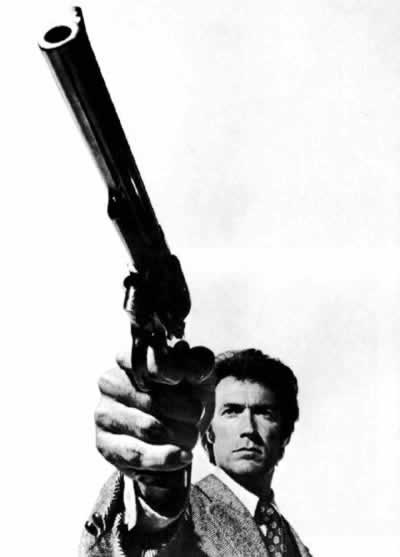

But Clint’s opening strategy was more intriguing, and more minimalist, in character. He said, “I’ve got this idea, about a teaser. One of the prop guys gave me this massive gun — and, getting ready for another take, I was just standing there. And the still photographer got this shot. What I’d like to do is just that — this picture, and your logo.”

That, in fact, became the opening expression for the campaign. And the rest is history:

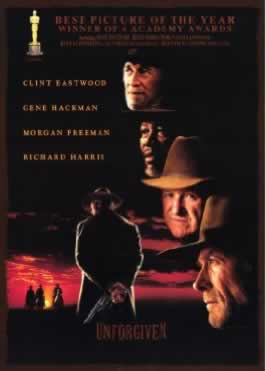

Typically, in Hollywood fashion, this went onward to a more thoroughly “legal” campaign structuring, with the appropriate portrayal of the stars, each appropriately proportioned, and each of their names, relevantly sized to their role distribution. The final seems more democratized and less dramatically impactive.

Why, this story, after such a lengthy departure from the western genre? According to Eastwood:

“There were a lot of people in the western genre who are no longer with us and it was a fascinating time. I did “Josey Wales,” and then “Pale Rider” and “Unforgiven.” I guess, because I had done quite a few westerns in the early days, that I might have made a few more, but I got away from it in the later Seventies and Eighties. I went off in different directions. But in 1980, I read a script called “The William Munney Killings,” which was the working title of “Unforgiven”; I thought, “this would be a great western, but I think I should be a little bit older to do it.” And so I bought the screenplay and put it in a drawer, and then, about 1990 or 91, I thought: “whatever happened to that?” I read it and fell in love with it all over again, and I said that this should be my last western.” And it was.

I went on to act as a designer for other efforts, over time — from “In the Line of Fire,” to “Space Cowboys,” to even creating titling treatments for Malpaso. Meeting him, at his studio office on the Warner Brothers lot, I was struck by his presence. Lean, tall, keen. That, in a way, is besides the point of the character of the human brand(ing) of Clint’s explorations, and development, during the course of his career. Physical attributes — that’s merely part of the story. It’s the mind and the psyche within that drives me to seek more. What I’m looking for is the spirit of the human brand, the true story of Clint Eastwood and how that essential quality has fired the enterprises of his creativity.

My first, early, connection with Eastwood — and the beginnings of the saga that traces his legendary career — started in the movie theaters and with the essentially mysterious character of his silently powerful essence — a force of natural reckoning.

The western was an early love for me — which goes back decades to my childhood. And that initial sentience of human brand power is the beginning of the legacy of the human firestorm that is Clint Eastwood, Malpaso Productions and his other creative enterprises. It’s the spirit that informs his early work, that lays the groundwork for his continuously evolving, yet consistently empowered, “brand” presence.

Born in 1930, Clint Eastwood is well known for his rough-voiced, tough guy, anti-hero roles in action and western films, particularly in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. His break as an actor came in 1958 when he took on the role of Rowdy Yates in the TV series Rawhide.

As Rowdy Yates, he became a household brand name across the United States and appeared throughout its seven year run from the first broadcast in January 1959.

A motion picture executive had spotted Eastwood on the series Rawhide in the early 1960s and thought he looked like the right kind of cowboy for their proposed, internationally framed series, envisioned by Sergio Leone. At 6 ft, 4 inches, Eastwood was a strong physical presence on set and he was prevailed upon to audition for Leone’s picture “A Fistful of Dollars” (1964).

The film was to be shot in Spain and, although it wasn’t the first western shot in such manner, and the film itself was evidently a tribute to Akira Kurosawa’s “Yojimbo” (1961), the film would become a cinematic benchmark in the spaghetti western genre that evolved from the mid-1960s.

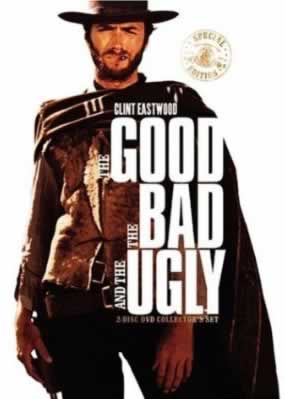

Eastwood was personally instrumental in building the essence of this personality — the Man With No Name character’s distinctive visual style that would later appear in the “Dollars” trilogy that followed. And in a way, that character would become a branding legacy — brooding, a kind of dark serenity, a squinting grimace, contemplative surveillance and calm under fire that would later become a global stylistic heritage. According to Wikipedia’s review, “he bought the black jeans from a sport shop on Hollywood Boulevard, the hat came from a Santa Monica wardrobe firm and the trademark black cigars came from a Beverly Hills store, although Eastwood himself is a non-smoker.”

This began the samurai-inspired retellings Man with No Name, an archetypal character profile, a establishing foray in Sergio Leone’s “Dollars” trilogy of spaghetti westerns, which include “A Fistful of Dollars” (1964), “For a Few Dollars More” (1965) and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” (1966). Later, after a string of other western films, he emerged as Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan in the “Dirty Harry” films, which have seen him become an enduring, masterful icon of masculinity. (IMDb biography)

1971 proved to be a professional turning point in Eastwood’s career. His own production company, Malpaso, gave Eastwood the creative freedom and artistic control that he envisioned, allowing him to direct his first film, “Play Misty for Me.”

The real catalyst for his global interception in theatrical history was his portrayal of the hard-edged police inspector Harry Callahan in “Dirty Harry” that propelled the Warner Brother’s studio group to its most successful movie at the box-office. Dirty Harry is arguably Eastwood’s most memorable character. The film has been credited with inventing the “loose-cannon cop genre” that is imitated to this day. Eastwood’s tough, no-nonsense cop touched a cultural nerve with many who were fed up with crime in the streets.

“Go ahead, make my day”.

“Dirty Harry” led to four sequels: “Magnum Force” (1973), “The Enforcer” (1976), “Sudden Impact” (1983) and “The Dead Pool” (1988).

Eastwood has won five Academy Awards—twice each as Best Director and as producer of the Best Picture and the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award in 1995. He has also been nominated twice for Best Actor, for his performances in “Unforgiven” and “Million Dollar Baby.”

His recent films, “Million Dollar Baby” (2004) and “Letters from Iwo Jima” (2006), and also earlier Revisionist Western films such as “High Plains Drifter” (1973), “The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976) and “Unforgiven” (1992) have all received a significant degree of critical acclaim.

“The Changeling,” his recent directorial effort, along with his newest offering, “Gran Torino”, continue his evolving legacy of taking the character of his cool brand character to a new level of direction, stylistic framing and production values.

The list goes on and on — and you can find more of the sequence of his creative credits, in acting, film, a political career, even his ownership of Pebble Beach and Teháma Golf Courses.

In reaching in, my sense — to the heart of the brand — is that the character of the person that has founded the “enterprise”, even in the attributes of the person themselves — genetically moulds the brand; and in this, that human connection there is the driver to the spirit of that foundation. As in the opening reviews in this series of Steve Jobs and his leadership of Apple, or Tom Ford’s advancement of his new retail line of men’s clothing, fragrances and accessories — and the incipient historical record and qualities of both of their legacies — the person ignites the brand; strategy is founded on a human connection; it’s not merely an engineered premise. Great brands shine with human vitality. And that great brand can be a person — alone — that captivates the attention of the experiencer. A passionate drive continuously inflames the fire.

Speaking of which, what is the driver? According to him… it is about guts and a willingness to risk, instinct and commitment, passionate enthrallment in the work and the process.

“It’s just a bit of work ethic. It becomes part of my life and, if I have any virtues, which are probably not many, I get fairly decisive about things. When I find something I like, I usually know it pretty soon and I don’t have to talk myself into much. I probably shoot from the hip. I say: I like this, let’s go. I don’t sit and dwell on it too much. I dwell on it as I make it.”

To a sense of maturity, serenity and the leap in action:

“I think I can make them [challenging movies] because I do them boldly and because I’m at an age where… what can they do to me? Once you’re past 70, what the hell can they do to you? You just go ahead and do it. If you put your toe in the water, it’s not going to work. You have to jump in.”

The instinct:

“I have the advantage of a lot of years of experience, and if I can’t put it together, then I should not be doing it. You have to feel confident. If you don’t, then you’re going to be hesitant and defensive, and there’ll be a lot of things working against you. In my career as a director, there’s always been some point where you get halfway through it, or three-quarters, and you go: what is this thing all about and why am I telling the story? Does anybody really care about seeing this? At that time you have to say: OK, forget that and just go ahead. What were your first impressions, all the things you can remember when you fell in love with the project? Put your head down and continue. You can never look back. I don’t have that now. I had that maybe 15, 20 years ago. I’d get that moment, the reflective moment. It would come and pass real quickly, but now I know it’s going to be there, so I don’t pay any attention to it. It’s just a little bird talking. You just say: get out.”

In studying the legacy of Eastwood’s output, over the course of nearly fifty years, there’s a thread to his character. As he notes, “We all boil at different degrees.” His creativity is a leap of faith, it’s following a gut instinct that celebrates the visioning of “his brand,” his point of view, his character — that assertively strides into the future of his experience expressions and his offering to billions of people on the planet. That might range from his love of music — playing it — to taking care of himself in remaining lean and strong enough to, at nearly 80 years of age, continuing to work and produce increasingly powerful content, and, in the mix of it all — living both sides of the camera — being an actor as well as a director. If brand is fire and story, then Clint Eastwood burns bright: “I tried being reasonable. I didn’t like it.”

References:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2007/feb/25/clinteastwood.oscars

http://www.starpulse.com/Actors/Eastwood,_Clint/

http://www.clinteastwood.net/welcome/alt/

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000142/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Eiger_Sanction_(film)

http://www.answers.com/topic/clint-eastwood

“Hollywood, as everyone knows, glamorizes physical courage…. If I had to define courage myself, I wouldn’t say it’s about shooting people. I’d say it’s the quality that stimulates people, that enables them to move ahead and look beyond themselves.”

“I’d like to be a bigger and more knowledgeable person 10 years from now than I am today. I think that, for all of us, as we grow older, we must discipline ourselves to continue expanding, broadening, learning, keeping our minds active and open.”

Imagery copyright: ©2008, Warner Brothers, Malpaso Films

TSG | e v e r y w h e r e