Designing things to be altered by fire.

Girvin

Smoke principles, brands and the waft of fire.

Firebrands.

I’ve been thinking about fire and smoke a lot these days, as you might’ve noticed. But like the proverbial A persona, I can’t relinquish the affection. It runs in the Girvin family. I like fire because of my father. I’m not sure about all of my brothers, but there’s a link. Fire, heat, passion, perfection.

Girvin

It’s nothing new, really, I’ve been writing about smoke for a long time. Bhutan, China, Tibet, fragrance, incense, birch, anything. Anything that burns and scents. Offerings. I believe in the idea that the transformation by fire is something mystical, clearly shared by millions of people, in the consideration of ritual — fire, the transitioning force, moves from the solid to the new molecular arrangement — burned — it’s sped up, accelerating atoms, until it’s forever altered. That process moves between the solid world, the physically known, to the mystical spirit word of the smoke — the story smoke of the Native American tradition. An idea, told on the wind of the waft of the effluent of fire, becomes the smoke of story. Watching smoke is bewitching and compelling — virtually everyone is hypnotized by the the smoked curls of this dust of fire.

What of firebrands? I’ve written about the premise of brands of fire, and those who make them.

I’d written sometime back about the work of Maarten Baas (movie at this link) and his collection of smoked furniture. These images of his work all come from his site.

As he describes it:

S M O K E

Pieces of furniture are literally burned,

after which they are preserved in a clear

epoxy coating. Except for three baroque

products, which are reproduced by the

Dutch label Moooi, all Smoke products

come from the Baas & den Herder studio

in The Netherlands. Since 2004 gallery

Moss and Maarten Baas collaborate

on the “Where There’s Smoke…” series:

a Smoke collection of well known

design classics of a.o Rietveld, Eames

and Gaudi. Besides this series, Baas

has done commissions for collectors and

museums around the world.

There are some other references, to his legacy (starting up, firing up — pardon the pun — just out of school).”

In June 2002 he graduated at the Design Academy a series of burned furniture called “Smoke”. His works were nominated for the internal “René Smeets-award” and also for the “Melkweg-award”. They lead to an invitation by IKEA to do a week workshop in France and got Baas selected for the rewarded improvisation / exposition of the Design Academy in Tokyo.

Literal, firebrands:

His design Smoke was adopted in the collection of Dutch label MOOOI, of Marcel Wanders. Thanks to successful presentations in Milan, London and Paris Smoke became known worldwide. Smoke furniture was bought by museums and collectors such as Lidewij Edelkoort and Philippe Starck.

The Smoke chandelier was part of the exhibition “Brilliant” of the Victoria & Albert museum in London.

In May 2004 a speechmaking solo-exhibition was opened with New York gallerist Murray Moss. “Where There’s Smoke” showed 25 pieces of furniture, all burned and finished of with transparent epoxy. Amongst others there were charcoaled classical designs of Gaudi, Eames, Rietveld, Sottsass and the Campana Brothers.

For the new collection of the Groninger Museum, Maarten worked on some furniture from the old collection of the museum. These were shown during the exhibition “Nocturnal Emissions” and purchased by the museum.

Also the Dutch Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam exhibited 2 of his Smoke-pieces in 2005 in an exhibition about pieces to be purchased by the Stedelijk Museum.” It goes on. Explore as you will. There was another reference to the idea of destruction — and beauty — in earlier blogs, one to Edward Burtynsky’s Manufactured Landscapes and the work of Michael Eastman and Chris Jordan — in each, the idea of dissolution (侘) forming a kind of wabi sabi. The inherent beauty of wabi sabi is imparted in rustic authenticity and worn utility and the aesthetics that emerge in this conjuncture.”

(Photograph,

wabi-sabi tea bowl Azuchi-Momoyama period, 16th century)

And in this character, the idea of wabi sabi links to pottery, which too suggests the attachment to fire.

Fire burns on.

The compelling jump for me, to this added exploration of fire relates to another exploration and connection — the Mulleavy sisters, the inspired designers of Rodarte, with whom I’ve had a connection — in correspondence. The real beauty of their work, a kind of couture of found wabi sabi, gestural gathers and inspirations from their wanderings — creative sojourns — moves beyond the fringe of the normal to the outbound of profundity of absolute creative abandon. Millions love their work, as do I. Blogged, earlier.

Rodarte sisters Kate and Laura Mulleavy appeared on Martha Stewart’s special siblings episode on Thursday to talk about several of their designs. They said they pull from things they saw growing up. Martha told them she would buy Rodarte undergarments, if they were to make them.” And interesting intonation – if there was one. But she’s the one that could afford to make such an off-handed response to the character of their work.

The sisters talk about their creation process — linked to the notion of found experiences from their childhood, growing up in northern California. The attributes, as they outline, relate to the notions of textures — things that they liked — in building ensembles, the assemblies of experiences in the design of their clothing. “We wanted to use fabric that seemed old — something that might’ve come out of the Depression.” Or we’ve “been playing a lot with leather, we wanted to build a kind of cage — every single detail was made by hand.” Condors, distressed materials, infinitely microscopic detailing, the dissolution of time, in memory, in the telling of the story.

And it is all about story — mythic or otherwise, which wends its way back to their upbringing, the sense of wonder, the exploration. One outfit relates to a creation myth — a kind of legendary telling; this story, a girl in the desert, gathering materials that related to her sentiments, a discarded quilt — burnt wallpaper, no less — she gathers them, then transforms — spontaneously combusting phoenix like, into something new. Textured silk linens that bore the patterning that they’d created — a burn pattern — then sanding the fabric, then tearing and actually burning the fabric creating in the end, a composite of six different fabrics. Burning goes from creative to destructive, as noted in Amanda Fortini’s New Yorker piece, written about the sisters, they burn fabrics, for fun:

“Laura pulled a sample of sea-foam-green polyester from the from a little heap near her feet.

“I hate that,” Kate said sourly.

“Me too.”

“Like, why do they even make it?”

“Should we burn it?” Laura wanted to know. “Who has the lighter?” She got up and walked a few feet to the bathroom with the sea-foam-green bit in her hand. The chemical smell of burning polyester wafted through the studio. “Stinky,” she said. Back in her chair, she rooted around on the floor until she found a scrap of silver lamé.

“I hate that,” Kate said.

“It’s awful. Let’s burn it.” She held it away from her body and and torched it with the lighter. The edges of the fabric began to flicker and curl. As the flame seared through the material, it left a scorched lunar landscape in its wake.

“Cool,” said Kate.”

Firestruck installations at Cooper Hewitt

Destruction — by fire or otherwise, as noted in the installation of manikins in the Cooper Hewitt show of their work — and this theming is

is part of the whole picture — the fascination with fire — smoke, the torch of creativity laid bare.

Firestruck installation at Cooper Hewitt

Such is the fascination with fire. For me, for others — Maarten Baas, the Mulleavy sisters and Rodarte — and before that, hundreds of years of other forms of the blackened firing of scent and darkening burning distress — ever transformational — the end of the world, and the beginning of another.

And what perfected summary of the allegory of fire, in transformation, than Gaston Bachelard’s “The Psychoanalysis of Fire.” Perhaps a true classic, more than 60 years old, it’s poetry, reverie, magic and pyromantic gesture is imbued with a graceful meditation:

“Fire and heat provide modes of explanation in the most varied domains, because they have been for us the occasion for unforgettable memories, for simple and decisive personal experiences. Fire is thus a privileged phenomenon which can explain anything. If all that changes slowly may be explained by life, all that changes quickly is explained by fire. Fire is the ultra-living element. It is intimate and it is universal. It lives in our heart. It lives in the sky. It rises from the depths of the substance and offers itself with the warmth of love. Or it can go back down into the substance and hide there, latent and pent-up, like hate and vengeance. Among all phenomena, it is really the only one to which there can be so definitely attributed the opposing values of good and evil. It shines in Paradise. It burns in Hell. It is gentleness and torture. It is cookery and it is apocalypse. It is a pleasure for the good child sitting prudently by the hearth; yet it punishes any disobedience when the child wishes to play too close to its flames. It is well-being and it is respect. It is a tutelary and a terrible divinity, both good and bad. It can contradict itself; thus it is one of the principles of universal explanation.

“In one Australian tribe the legend is very amusing, or, rather, it is because a bird is being amusing that it succeeds in stealing the fire. “The deaf adder had formerly the sole possession of fire, which he kept securely in his inside. All the birds tried in vain to get some of it, until the small hawk came along and played such ridiculous antics that the adder could not keep his countenance and began to laugh. Then the fire escaped from him and became common property.”

Girvin

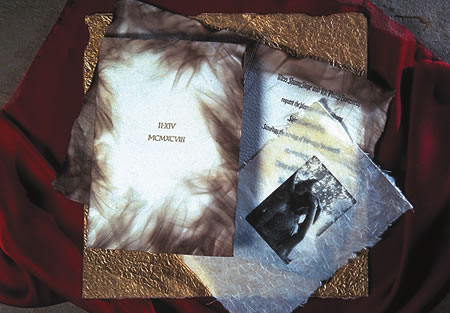

Fire, truth, transformation, magical — an enchanting presence — even as noted, as the founding principle of the firebrands, noted above. I have one distinct recollection, working with Sharon Stone on a project — her wedding invitations, 1998. She’d call, with each iteration of the design — and dial direct to my desk; I was never there. So there would be breathy, smokily intoned messages about her directorial details — in many instances revolving around the concept of the “burning” of her invitations. She would say, in her messages, “Tim, more burning, more smoke — I really think that we can use more…” In the end, the invitations were shipped overnight, boxed FedEx internationally — wrapped in silk, with blackened ostrich feathers, bead work an printed on multiple stocks of hand torn, letter-press printed hand-made stock, each one burned and smoked at the edges, an intriguingly evocative effect. Risky, time-consuming, but enthralling. Everyone showed up.

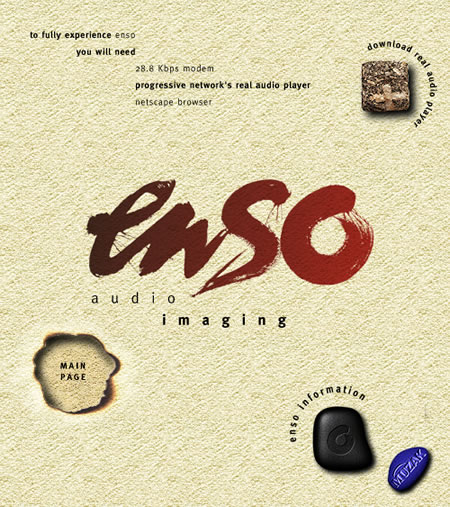

Another flaming interception — the burning of holes in our interface | UX for Muzak; the early point being a holistic “touching place” — fire-grazed, etc., in building the zen-space of the customizable place/ambient brand.

Girvin

I love fire. And smoke.

Tim | S a c r a m e n t o, C a l i f o r n i a

––––

Exploring brands of fire,

brands of passion:

GIRVIN FIREBRANDS

the reels: http://www.youtube.com/user/GIRVIN888

girvin blogs:

http://blog.girvin.com/

https://tim.girvin.com/index.php

girvin profiles and communities:

TED: http://www.ted.com/index.php/profiles/view/id/825

Behance: http://www.behance.net/GIRVIN-Branding

Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tgirvin/

Google: http://www.google.com/profiles/timgirvin

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/timgirvin

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/people/Tim-Girvin/644114347

Facebook Page: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Seattle-WA/GIRVIN/91069489624

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tgirvin