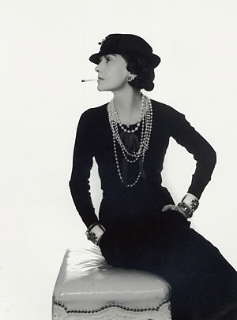

Form language and brandstory: Coco Chanel

There are living icons, human brands, and there are others, that create that character after their passing.

Gabrielle Chanel is someone that I should write about, considering the concept of the human brand. But not now.

What I’ve been thinking about is the idea of design icons — what sensibility drives the spirit of a brand to then create a product representation that is truly unforgettable. I’m sure that instantly you have something in your mind that speaks to that language — something that you relate to, perfectly, unforgettably, warmly. You are holding an object that, by memory, you hold close to your heart. Something that seen — from afar — is instantly recognizable. The point is that the character of a brand language, and the story that lies in it, can build the spirit of a brand. And Gabrielle Chanel was sufficiently driven by the energy of her personal positioning that she simply couldn’t leave her hands, discerning mind and designing eyes off the proposition of her first fragrance. And that story, unto itself, is wholly remarkable — her direction of the design of the scent.

But in studying more about the design ethos of Coco Chanel, (actually, I named my second-born daughter Gabi, after her) and the profound power of her branding consciousness (surely not even known as “brand”, back then — image, I’d presume).

As Alice Rawsthorn offers, “The packaging was to be modern, too. Chanel lobbied for a plain glass bottle, rectangular in shape. The label was another rectangle in plain white with black lettering in the sans-serif style. Beneath the stopper was a black circle containing a white sans-serif C.

The bottle looked dramatically different from conventional ones and echoed the work of Chanel’s favorite artists and designers.” The geometric styling was evocative of the newly modernist forms of architecture that were emerging, the influence of Le Corbusier finding the foundations of its groundswell. The hyper modernism of the type design spoke to a new classical discipline — restraint, elegance, coupled with san serif principles — as newly defined by designers Jan Tschichold, and other leading practitioners of the new socially generated modernism.

As a directrix of design strategy, Chanel softened these influences in her bottle. The glass edges were gently radiused, making it seem less harsh in character and more . She achieved a similar effect with the lettering. Whereas Tschichold and Moholy-Nagy were experimenting with sans-serif typefaces in lower-case letters and ditching old-fashioned capitals on the principles that they were not failing the spirit of democracy but, like decorative scribbling, unnecessarily distracting the frenzy of modern life, Chanel chose the contrary path. By using nothing but a delicately disciplined futurist capitals, she created a sense of rigor, beauty and restraint that modestly celebrated what treasure lies within. Nothing out of hand — just, the simply elegant message. The minimalist character, even a modernist display on the bedroom vanity, it say virtually nothing but the refined confidence of the luxury that it represented in its launch. “These subtleties engaged No. 5’s modern, but not too modern, bottle to Chanel’s wealthy clients and prolonged its appeal. An undiluted interpretation of a 1920s aesthetic would have remained rooted in the period,” Alice Rawsthorn notes, “a similar effect in the 1920s furniture of the Irish designer Eileen Gray. She took stylistic cues from progressive designers, like Marcel Breuer and Charlotte Perriand, but refined them by expressing their geometric forms and industrial materials in soft curves and sumptuous finishes. The result is unmistakably modern yet quietly ambiguous, and looks equally appropriate in any period.”

The No. 5 bottle has also benefited from focused brand management. Even after Chanel’s death, the company shrugged the evolutionary temptation to change, other than in the most subtle manner. And, as well, the layering of competition was sparse — few intriguingly designed perfume bottles surfaced since 1921. It started like this, “Chanel’s archrival, Elsa Schiaparelli, kicked it off in 1937 with her surrealist-inspired Shocking bottle, shaped like Mae West’s torso. Jean Paul Gaultier produced a witty parody of it for his first perfume in 1993, while Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons sealed her scents in plastic sheeting.”

That discipline laser focuses on the centered legacy of “simply being the best in the world, for now, for ever.” The spirit and inspiration of Chanel founder Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel can be found in two “headquarters”—Paris and New York City.

The elegantly timeless designs carrying the powerful Chanel monogram still originate in Paris from the creative team led by Chanel veteran Jacques Alain Helleu, creative director for Chanel worldwide. However, the teams responsible for bringing those uncompromising disciplines into reality, work in concert in Paris and New York to guarantee a singular, carefully orchestrated Chanel experience worldwide.

Scott Widro, v.p. of materials management and manufacturing, is a colleague of Helleu’s at Chanel. Widro’s counterpart in Paris is Michel Dupuis, senior v.p. of package development in the Paris headquarters whose role manages a relatively small number of suppliers and converters and having tightly guarded control on every aspect of product and package production.

Dupuis says the Chanel packaging department operates under a kind of motto: “We have one product for one world.” Global launches are truly integrated international launches of a singularly consistent product and package, coordinated to appear nearly simultaneously around the world.

As a leading haute couture brand, consumer expectations of Chanel are nothing less than perfected quality — Widro poses: “How do we separate ourselves from the rest of the pack? That’s quality.” Practiced quality. Precision, purity, management: Chanel is still a privately held company that prides itself on the all-natural ingredients of its products, the purity of design and materials, and the dedication to stay true to the Chanel tradition — the original telling, the founding discipline and dreamy romanticism of Gabrielle’s ideals — made with its perfume ingredients, creates its own concentrates, and even, as Coco did, touring the fields of Provence to find the right perfections…quintessentially, the heart of the story, Gabrielle Chanel.

tsg | london

—-

Exploring community, storytelling

and relationships | the Human Brand

Creativity | the alignments of personal truth:

https://tim.girvin.com/