A contemplation on gratefulness

Notes on the death of my father, George W. Girvin, 7.05.2024

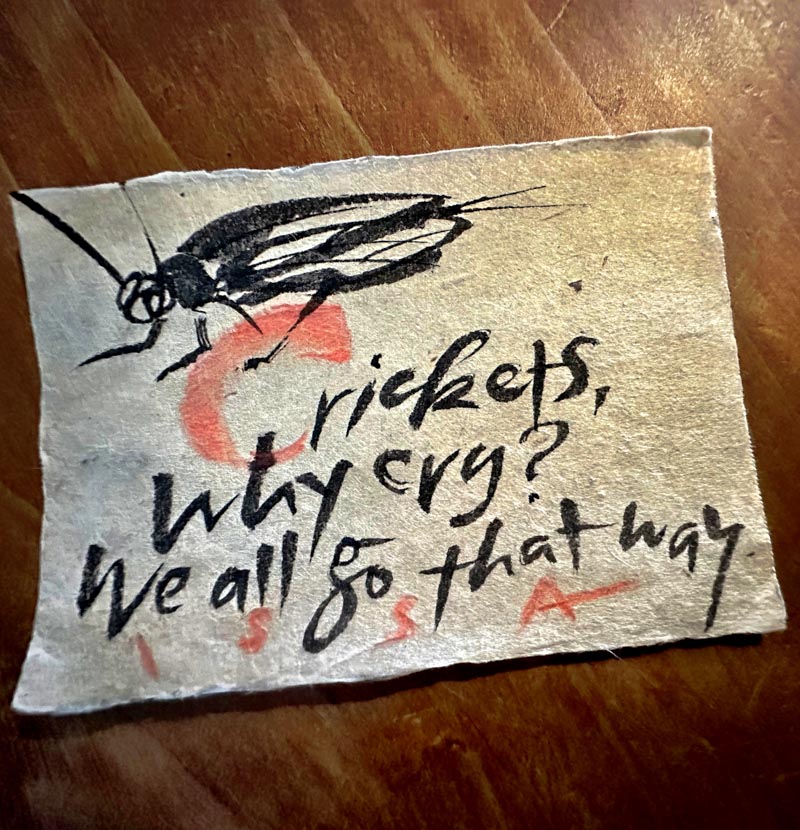

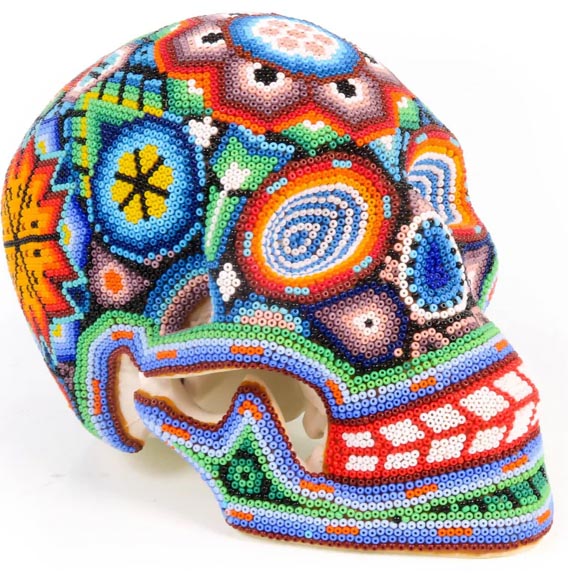

“Why do you have skulls around you, everywhere?, I mean, you’re always wearing skull scarves, rings, all that.” Someone asked me this question. I have a long history with skulls, skull art from México, Bali, Tibet, Bhutan, other countries—and, perhaps, it comes down to the recognition of the ever presence of this one inescapable fact. As Issa Kobayashi offers, the 18th century Japanese master of haiku poetry, while crickets balefully sing, there is no need for such a plaintive song, since, eventually, we all go that way. Away.

I take a moment—considering the passage of my father, then Uncle Graham and earlier the abrupt death of my Mother’s sister, my Aunt Ginny—Virginia—that has added to the difficult journeying of that and now this year. During that time, the overarching spirit was drear, laden with misfortune, while the specters of illness and death simply seemed rampant, pervasively persistent. And it goes on, ever-present—as in Dad’s passage, this last week. Still, robust journeys offer long pathways of wonderment—and this was the ever-empowering legacy of my father, a spectacular life, finished with a homebound passage in goodbyes from each of us. And what better departure could we ask?

The formula of life abides in the certainty of death, a bound weaving with the persistence of the certainty of this equation.

So, during this time, “what’s the Girvin deal with the skulls – why are there so many skulls around you, all the time?”

They are reminders.

A quick answer might be that when I was in college, I studied Tibetan Buddhist theology—and proffered a theory, founded on a theses—built on the thought that the originating big influence for Skull Kulture for American tattooists, bikers and hot rodders actually came from Tibetan skull imagery.

My theory, anyway.

But skulls, a reminding?

Now is, perhaps, a fit time to answer that question with a story.

Most people don’t know that my relationship with the symbology of skulls that goes back far before my connection with Alexander McQueen, rather, it goes back to the death of my youngest brother Matthew Girvin, which—winter, 2001—was laden with momentary and monumental mystery [an email, a call attempt and then evanescence, and vanishment] in the intertwining of meaning, content and message.

When Matt was killed, my relationship to Death changed drastically. I felt that I had to get close to Death and keep it by me—all the time. To walk with it, and through it, as I walked the journey of his passage from there. To here. And still, to this day, I keep it close.

Once, an uncertain and wavering wraith outside of mind, it came close, held me and took dear ones, nearby.

Suddenly, I realized that Death was nearby, just over my shoulder, all the time.

As my family came together to grieve, I realized that, as the eldest brother, and the one that had lived longest with each of my family members, other than my parents, I needed to contribute something to processing the pain of Death — what is that journey, what do you do about it?

Someone dies.

Then what?

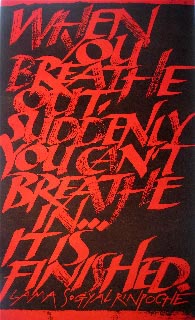

As it comes again, with Dad, I think about that—and come back, another day, to this question—it is these two things—two pieces of counsel that I can offer. I walked down that path even earlier, in Seattle, with Sogyal Rinpoche—a Tibetan Lama exploring Death — and I designed art in homage to that teaching.

It goes back.

And I go back.

I can remember the first time that I was exposed to a Tibetan vajrayana teaching presence—a human distillation of Himalayan spirituality.

It was Sogyal Rinpoche, decades back. Sogyal Rinpoche (born c. 1950, several years before me, died 2019) is a Tibetan Dzogchen master of the Nyingma tradition. He is the founder of Rigpa and the author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. That book came out sometime after my connection with him.

He was a relatively young man. And I’d been asked to create some art for him on a poster. That was all about death.

And breathing. And exhalation. And the quote that I’d rendered, with a wet brush, was about breathing in, breathing out. And you keep breathing. You keep breathing till you can’t. And you exhale. And that’s that.

But the encounter, aside from the presence of this person, this Rinpoche was my first live exposure to Tibetan Buddhism. From there, off and on, that connection filtered in and out over time. There was the crazy wisdom of Chögyam Trungpa. Intriguing, but sad, the short-lived.

One:

LIFE.

GOES.

ON.

— while it’s profoundly difficult for some of us, at this point [the arrival of Death,]

to believe it, the sheer miracle of life, and all living things,

is endlessly churning and cycling, tides pull and push, gravity reigns, rain falls, the oceans roil—

and in this, all of this, in ways that none of us know.

Wholly.

It’s a teeming regeneration, and as you get a bigger or smaller glimpse, or older or younger in your ability to see, or come full face to the presence of Death—

LIFE.

STILL.

GOES.

ON.

For me, it comes down to this play on word and work;

Life—the word—what it is?

In a word, etymologically—it is to be “left—living.”

That is, some might interpret the etymology to be; “to leave,” but actually—it is to be left.

You live.

On.

That is the conclusion to the cycling of the wording:

LIFE. GOES. ON.

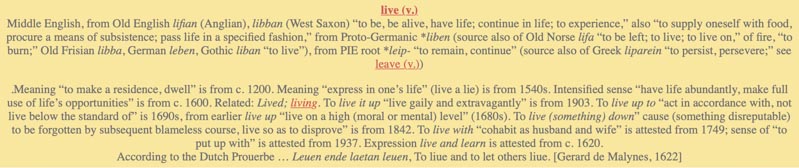

That etymology—spells out, as below.

FROM

MY BUDDY

DOUG HARPER:

And two.

What’s sown,

that learning?

Death is always here.

Know that and keep it around.

Skulls are a good reminder.

After Matt passed I started adding skulls to my landscape—

my place on Queen Anne is peopled by a long collection of

Mexican hand-painted skulls from skull artists in various provinces.

They’re all over,

everywhere.

I did that to keep Death close. I offer this too, as a key advice to anyone in the throes of the passage of another.

Every day—keep them around, keep them close—pictures, objects, everyday, staying around.

The process of grieving should be one of daily observation

of passage — an altar of imagery of loved ones gone — something that you could see, every day.

That proximity will help.

Every day, you go on.

And

Life.

Goes.

On.

So too, should you watch

this poetic rendering by Leonard Cohen.

That voice.

Onwards to the day.

wishing well —

timothy shaw | Osean Studios,

in meditation

on those near and far.

DESIGNING ENVIRONMENTS FOR HEALING + HEALTH:

PLACES | RETAIL | RESTAURANTS | SPAS | WELL CENTERS