The presumptive nature of design is that it’s magical.

We’ve commented on this proposition extensively.

Design as interpretation

Design: it is a transformative tool that translates content from one tier of comprehension to something new—a altered plane of understanding, that is a transmogrification—and it could be a complete transition from one layer of perception, wholly modified to another, newly altered way of seeing.

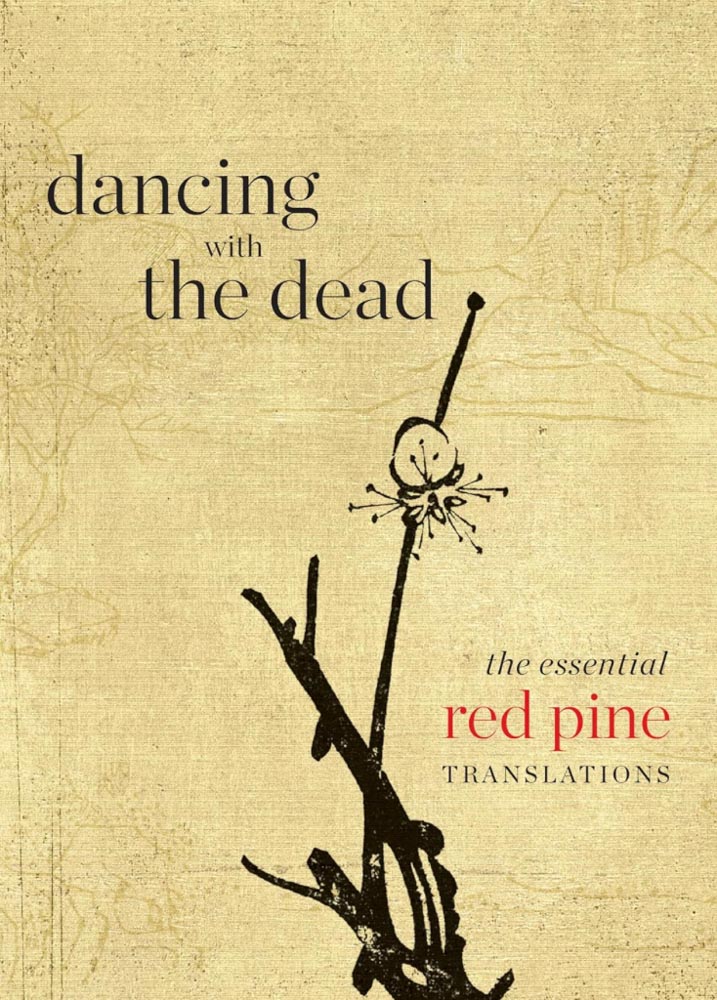

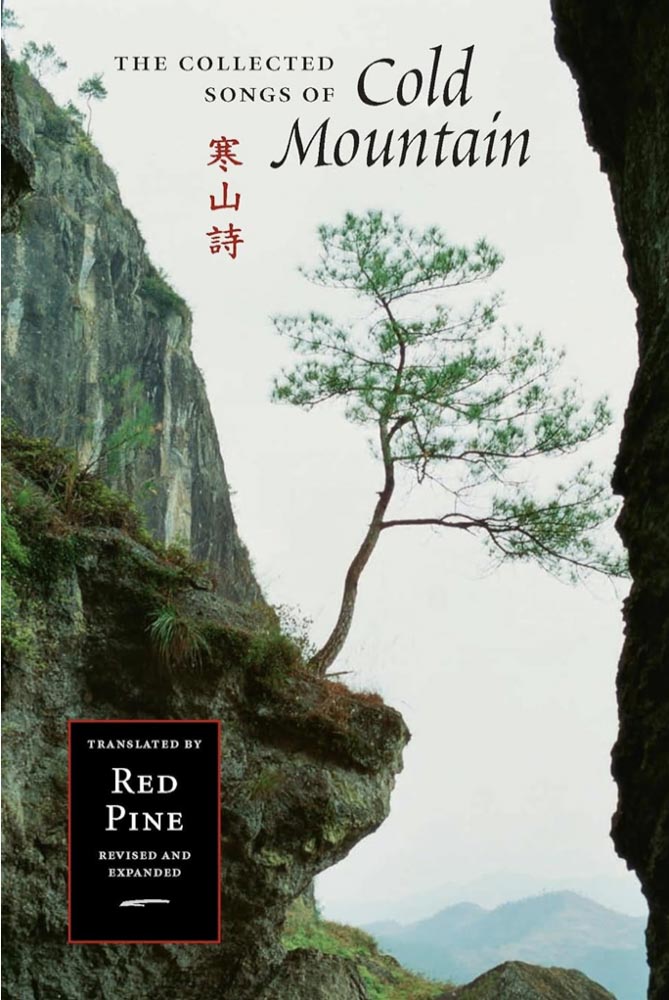

Translation, however, is another art—since it’s about the interpretation of content and the precise re-rendering of that textual content in a manner that speaks of the nature of the creator, and the precision of the interpreter in the journey of the original text; it is, as Red Pine notes, a dance with the dead, since his interpretation is particular to the observations, imaginings and extrapolation of the individual Chinese characters.

He dances with the dead in listening to, and walking around,

the journey in time and context to the emerging string of meanings.

This is, of course, where the notion of design—the transformative adjustment of a signal, a sign or signet that transports the viewer to a new place—differs from “translation,” which is a matter of holding to,

and interpreting, content in a manner that mirrors the author’s intention

that—in that translational visioning—pulls the listener, the reader

into a new construct of beingness in listening or reading.

Speaking of meaning in the context of translation, I would ask—“what’s the meaning of that word?”

Where does that come from?

As Phil Harper notes,

translation (n.)

mid-14c., “removal of a saint’s body or relics to a new place,” also “rendering of a text from one language to another,” from Old French translacion “translation” of text, also of the bones of a saint, etc. (12c.) or directly from Latin translationem (nominative translatio) “a carrying across, removal, transporting; transfer of meaning,” noun of action from past-participle stem of

transferre “bear across, carry over; copy, translate” (see transfer (v.)).

Given the dancing with the dead allegories, it’s curious that the origin of the word lies in skeletal transitioning—moving the bones.

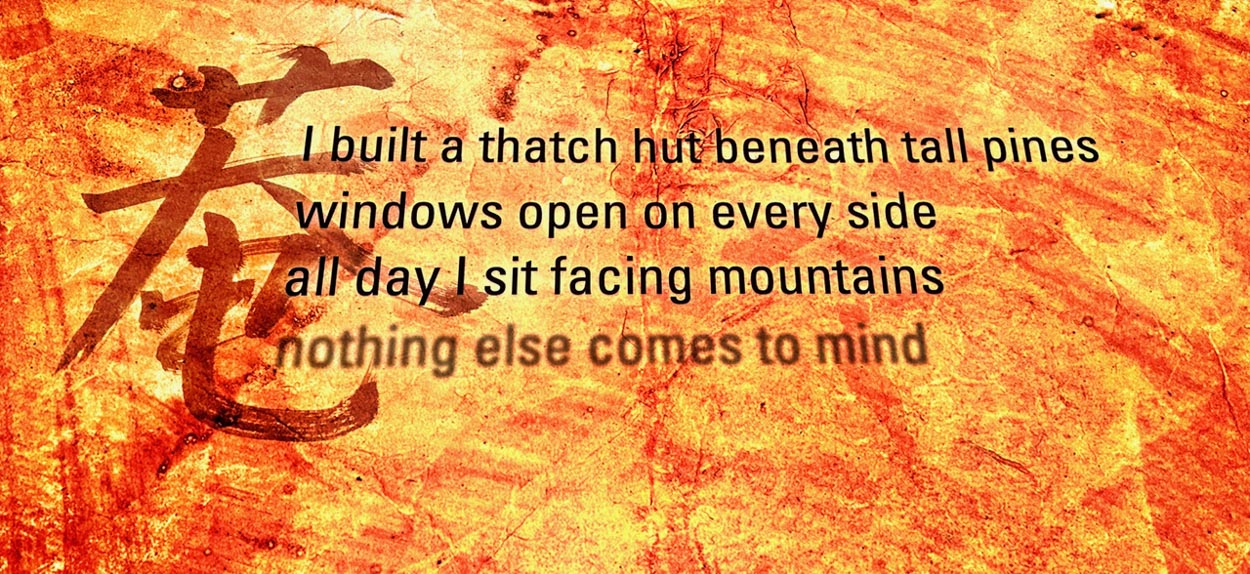

For GIRVIN, of course, as motion picture designers, we were brought on as creative directors for the main title and interstitials. In a string of collaborative explorations, we worked towards a single character, juxtaposed with a restrained contrastive typographic system, and overlaid on a striking antique Chinese handmade paper from GIRVIN’s collection of rare mulberry, rice, linen and cotton sheets, mostly made in the last 100 years.

Single character.

And, in a set of sliding dissolves—

a translation appears.

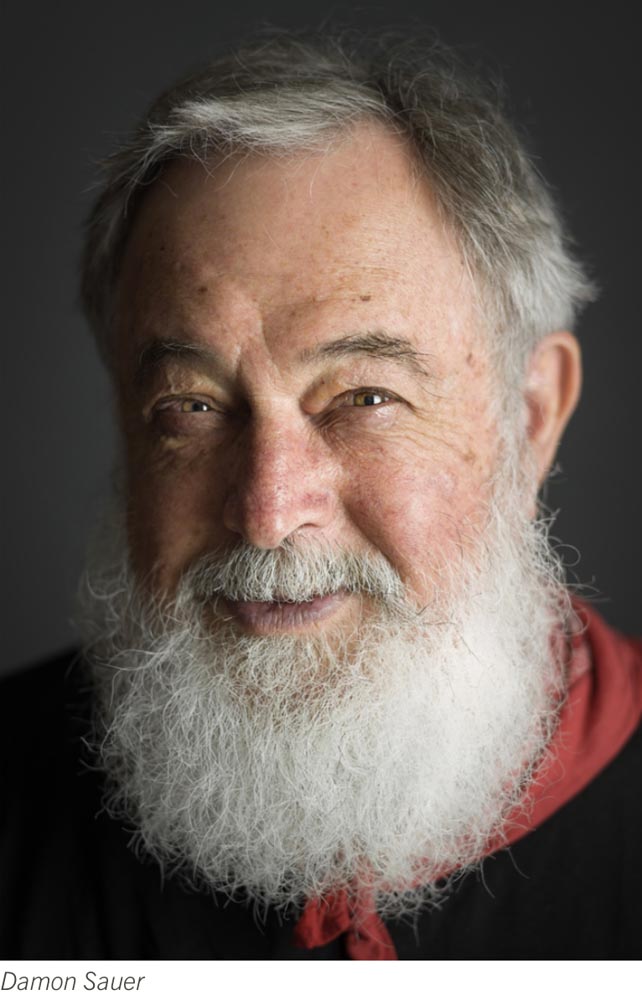

Red Pine’s journey is a fascinating one—and worth the walk and wander with him—since he is, as an exemplar, a translation unto him—the journey from Bill Porter, explorer of Chinese culture and Buddhist meditation, to Red Pine, one of the most renowned translators of ancient Chinese poetry.

I went to the first premiere—Port Townsend, then the international opening at The Egyptian in Seattle,

with a substantially larger crowd, if not a full house.

Explore more—Red Pine’s particular legends.

Buy one of his books.

Explore the tradition of ancient Chinese Hermit and the quest for joy.

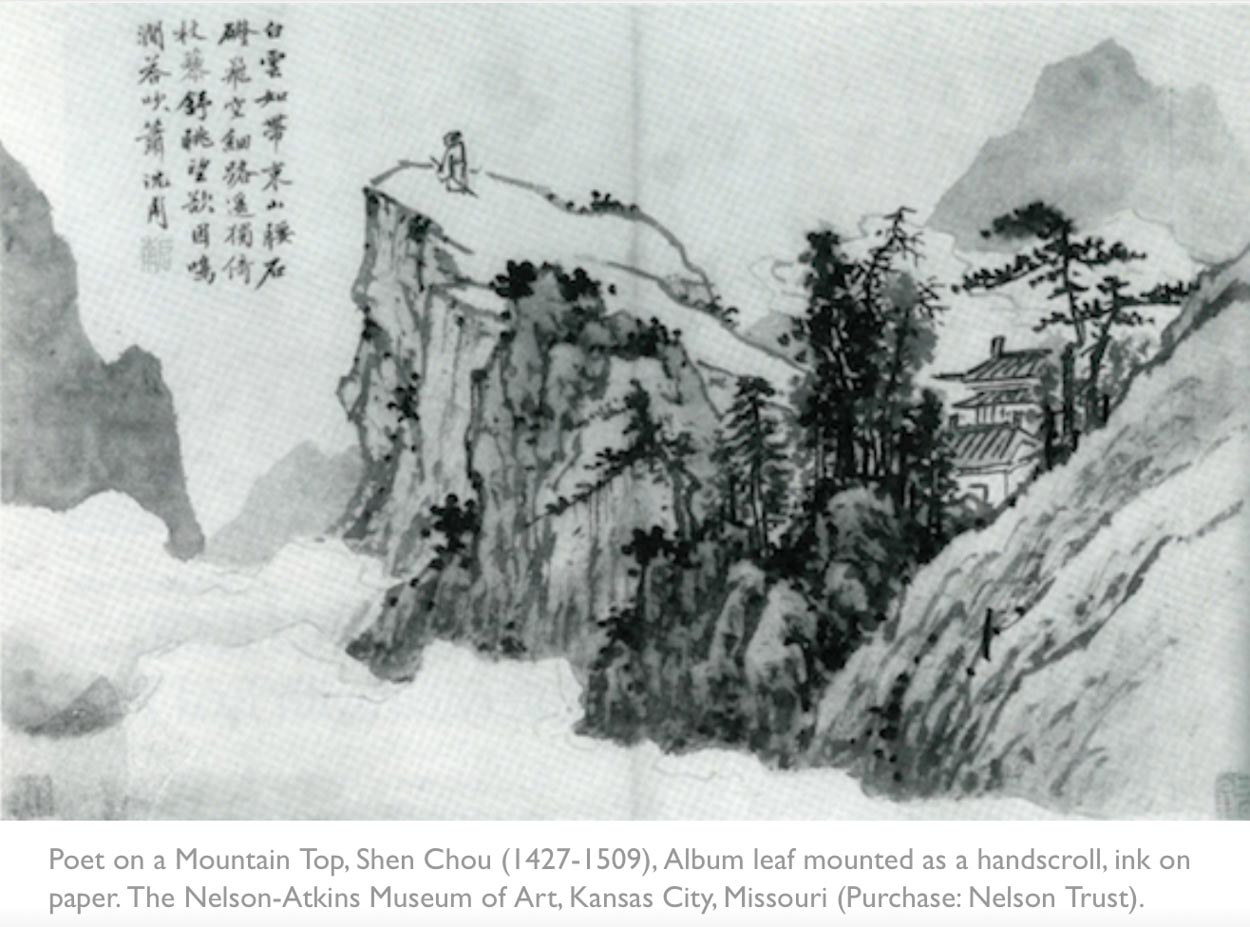

Examine the Chinese impressions of the hermit poet.

And could you get there?

More on the work, GIRVIN’s role, here.

Find help.

Tim | GIRVIN | Strategic Brands

Digital | Built environments by Osean | Theatrical Branding

Waves | Art | Talismanika™ | Oom Carpet Arts

Technology Branding | Destination Brands

Projects in everything brand.

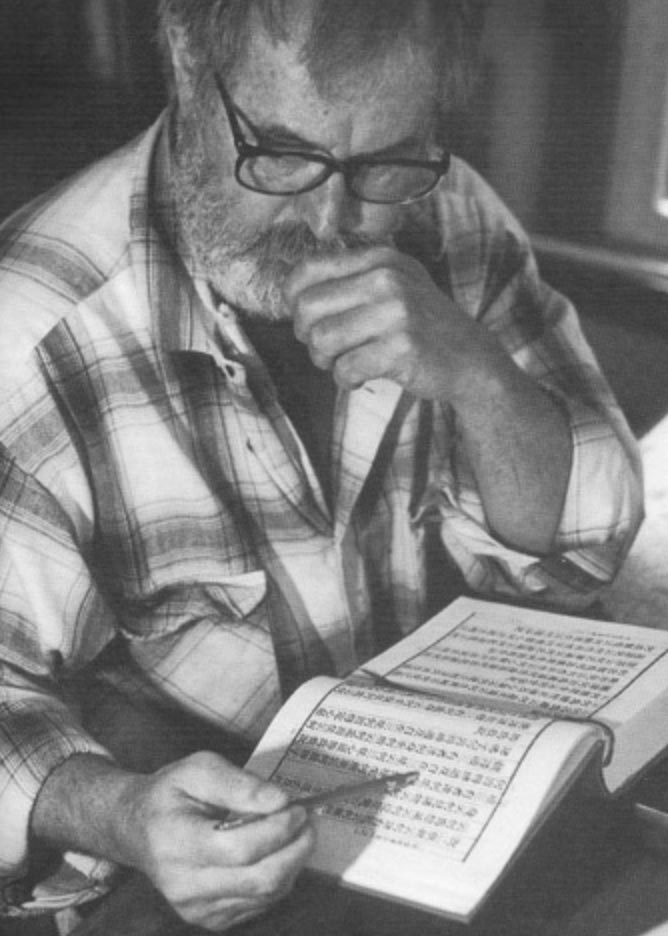

Red Pine, a reading:

“What I do now is more of a performance,” he says. “Before, I was usually sort of reading the lines like an actor, but now I perform the book — what I do now is closer to dance. The words have to follow along my physical feel for the rhythm, the feeling of what’s happening in the Chinese poem. I don’t see the Chinese as the origin anymore. The Chinese was what the authors used to write down what they were feeling.

“I’ve gotten so used to the words I don’t have to think about them anymore. I’m more concerned with the spirit. I don’t think I have a philosophy of translation, but you have to be very open.

“You’re trying to get into the heart of another person. I’m fortunate I’ve found materials that present deep hearts. That’s the way I’ve responded with the passion I have. I’m fortunate to have run into the Buddha, Bodidharma, Cold Mountain, Stonehouse and the other Buddhist poets.”