Exploring the principles of art, craft, making and the philosophical vision:

Brooklyn Museum: http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/murakami/

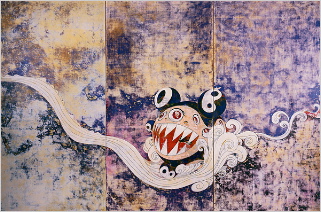

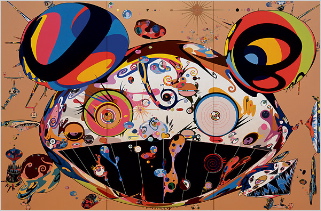

What about Takashi Murakami?

“the difference inherent in Japanese and Western artistic practices, and the frustrating “non-art?” status that much of Japanese art bears, both within, and outside of the country.” My first response to this was to and market artistic works in non-fine arts media. But after that, I thought: “why not just revolutionize the concept of art itself?

The tradition of art, crossing to luxury, and luxury, returning to art, isn’t a new one. In fact, gathering the threads of time, it’s likely possible to find networks between the artists of a time and the luxurious outcroppings of the cultured — and back again. In fact, one might surmise that some powerful brands, even luxurious ones, from the realm of the past, found their strength in the founding hands of the artist.

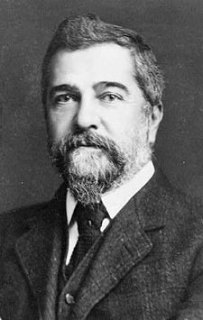

References might be found in the opening principles of Louis Tiffany. The genius of the Tiffany presence, originating in the middle of the 19th century, and closing a career in the middle of the 20th century, was founded on an extraordinary inspiration of matching beauty and manufacture in artfulness. Marvelous, the character of the work, the inspiration of the man. (Can that be said of Takashi Murakami?)

L.C. Tiffany

There’s a long story in the legacy of the man’s work — and it’s surely too complex and rich to tell here — but, it’s worth exploring here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Comfort_Tiffany#Career

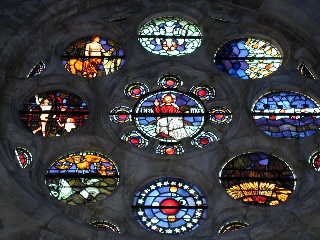

The Holy City, by Louis Comfort Tiffany

Stained glass window at Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church,

Baltimore, Maryland © James G. Howes

One might surmise that the man was the brand — he was the craftsman, the visionary, the businessman that mixed the highest inventions of the artisanal traditions of making with the range of implemented commerce. The bridge between the ideal — and the real. (Murakami, then, too?)

Tiffany’s dragonfly lamp

Tiffany jewelry

The gesture is the link between a person, a vision and a branded dream. Hence the jump to Murakami.

There’s a slightly different spin to the story, in the peculiarly turned telling of Murakami’s creativity and his newest installation here:

I’m not done with the sense of history, impacting in a way, the character of Murakami’s actions — yet. And the concept of artists being tied to the conceptions of luxury as art | art as luxury is still less than fully examined. This allusion in formula: art + luxury = commerce, extends backwards in time to the character of the founding dreams (again) of the arts and crafts movement that was the galvanizing influence for Louis Tiffany, Tiffany & Co. — that of William Morris.

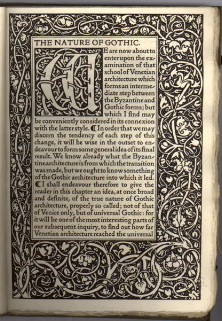

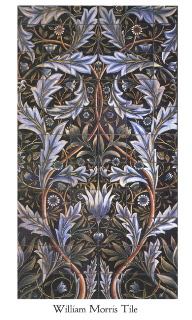

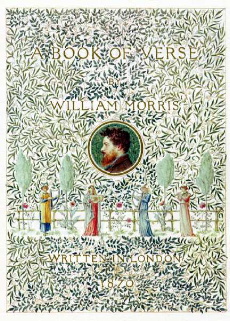

Morris was born earlier in the 19th century, enough so to influence the spirit of Louis Tiffany. His visioning was, like Tiffany’s, comprehensively expressed — in all things. William Morris’ expression of objects, architecture, decoration, literature, books and arts – the conceptions of arts and crafts expression, thoroughly integrated — were broad, and widely felt. While Morris’ sentiments were for a hopeful generation of artful utilities that could be experienced by the many, much of what he and his school created were for the rare and the few. His lush books, published by the Kelmscott Press, for example, were limited edition masterpieces of production. But, obviously, could only be explored by a relatively small and well appointed audience.

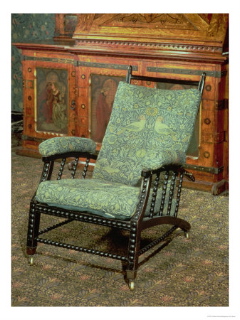

The spirit of that foliate and full expression of decorative richness was applied to virtually everything — ranging from architecture to furniture and a wide assortment of affiliated artists and evangelists championing the visioning of his work.

Some patterned wallpapers, textiles and tiles:

Art and poetic treatments:

His architecture | the Red House:

The furniture | William Morris:

Glass work — William Morris:

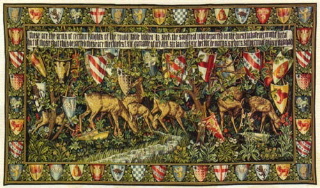

Tapestry work from the Morris studios:

What I’m interested in are created worlds — that is, works that are integrating visioning that ties to holistic expressions in culture. For commerce. And in this review (just for the sake of expedient reference) — I’m only exploring one distinct time framing (there are surely others) — from the shifting portals of the 1700s, to the new movements of the 1800s and the turning transitions to the beginnings of the 20th century.

That string comes from a sequence that might have been the founding of the arts and crafts ideology, as a backlash to the harsh industrial age of early Victorian transformation, from the late 18th century to the emergence of 19th century. Dreadful societal conditions, promulgated with the advance of hardened forces in the industrial revolution — similarly challenging the human condition. Arnold Toynbee’s lectures: “The Industrial Revolution, ‘the catastrophic interpretation’ of the whole of the industrial period as a time leading to ‘a rapid alienation of classes and to the degradation of a large body of producers.”

Work took on a dreadful toll. There were the rich, there were the poor. The arts and crafts took on a kind of humanist, even Socialist character, rejoining earlier simpler times, when things might have been, at least in the minds of John Ruskin, one of the key founders of the movement, more beautiful. That political reference emerged in a kind of communal sharing of wealth, the spreading of the goods. That movement’s opening, lead to an entire school of thinking — and artists that gathered to its core. William Morris, a builder of worlds. Louis Tiffany, a builder of idealized wonderment.

And now, Murakami, a builder. A philosopher. An artist. And the superflat otaku.

What I note about Murakami (and a little of the philosophy of his made world) is a kind of similarity of vision in bringing the dream of his expressions out into the larger sphere of cultural experience.

To reference, for example: “Louis Vuitton has created a temporary store within the retrospective exhibition of works by Japanese artist Takashi Murakami. The store’s presence in the museum symbolizes the interweaving of art, culture, fashion and commerce that has become a fundamental component in Takashi Murakami’s philosophy.”

That sounds a little familiar. Some critics rail against this link between art, luxury, commerce — but it’s not the first time that these features have been conjoined. Callen Blair notes: “The purist Cassandras are crying that it’s another example of a museum cozying up to a corporation and engaging in commercialism.” She continues — “The Vuitton outpost isn’t a museum partnership with a corporate brand or a gift shop. (LAMoCA isn’t even making any money off the shop.) It’s part of Murakami’s art. His interest is in knocking down the wall that separates high art from low art; that’s why he makes everything from paintings for blue-chip dealer Larry Gagosian to the ubiquitously-known Vuitton bags to mouse pads and cell phone caddies sold through his company Kaikai Kiki. A retrospective of Murakami’s career that didn’t include a retail space of some sort would be incomplete. And museum officials recognize that — they told the New York Times that the boutique “symbolizes the interweaving of high art, mass culture and commerce that has become essential to Murakami’s philosophy.” William Morris?

Photo by Gion

A grounding principle to Murakami is a stride: “I don’t know if it’s a philosophy, but the thing that impulsively comes to mind as an artist is to step into areas where people don’t go.” But he counters this positioning in the bridging of east to west, in the character of his experience as being a Japanese designer with a sense of historical context: “I would like to spread “humbleness” and “moderation,” two things that are still unknown in terms of their worth in the West and around the world. These have been crucial design concepts in Japanese art and society for centuries.” Humble. hmmm…

That idea of bridging the spirit of the present to the past is similarly the guiding principle of the other artist’s worlds (and works) that I’ve suggested align with this exploration. William Morris was a facile student of the Medieval. Morris’ works in this manner, attempted to bring this character back into the fold of commercial and cultural context in the 1800s.

So too does Murakami seek bridging — the past, to the present: “Murakami attended the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, initially studying more traditionalist Japanese art. He pursued a doctorate in Nihonga, a mixture of Western and Eastern styles dating back to the late 19th century. However, due to the mass popularity of anime and manga, Japanese styles of animation and comic graphic stories, Murakami became disillusioned with Nihonga, and became fixated on otaku culture, which he felt was more representative of modern day Japanese life.”

And, in the character of the workshops and settings of production — Murakami relives that development from the arts and crafts, imbuing philosophy with extended production — and branded, signature products:

And a grouping of discrete Murakami cultural expressions — made, en masse: “In 1996, Murakami founded the “Hiropon factory,” a studio with assistants to produce his work. With success, the Hiropon factory gradually grew into a fully professionalized art production studio and also an artist management organization. In 2001, Murakami registered his organization as Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. Today it employs over 100 people, with operations in both the US (in Brooklyn, New York) and Japan. Kaikai Kiki puts on an art fair twice a year, GEISAI.” Like the workshops of Morris and Tiffany.

“Murakami formulates ideas and actively supervises the production of work, but he does not directly paint or sculpt the finished works. In addition to producing art works for exhibition in galleries and museums, KaiKai Kiki is responsible for the design of an enormous range of mass-produced products featuring Murakami’s signature images: vinyl figurines, plush toys, keychains, t-shirts, posters, and more.

Kaikai Kiki also functions as an artist management organization and has seen remarkable success in creating a domestic and international market for new Japanese art. Many of Murakami’s assistants are also artists who are exhibiting their work internationally.” (Wikipedia)

The conclusions — as an aside to criticism of his works, the alignment with Louis Vuitton, the “shop” at the Museum — it’s about creating worlds. And letting commerce be a kind of bridge between the promulgation of the principle to spreading the proverbial word. To world.

What do you think about Murakami? Is it possible that this notion upsets the principles of art — and the selling of it; is art, luxury, simply something that speaks to the few? Or, could it be another philosophy — like the spirit of William Morris, or Louis Tiffany, an ideal that brings that dream holistically to the world, broadly accessible?

What that world looks like, from the NYTimes, Julien Jordes:

Murakami production site: Kaikai Kiki Co.

http://english.kaikaikiki.co.jp/

The Daily News:

http://www.nydailynews.com/ny_local/brooklyn/2008/03/26/2008-03-26_murakamis_vuitton_bags_for_sale_at_brook.html

Gothamist:

http://gothamist.com/2008/04/02/_murakami_brook.php

Anime News Network:

http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2007-12-12/takashi-murakami-exhibition-heads-to-brooklyn-museum

Lee Rosenbaum’s cultural commentary:

http://www.artsjournal.com/culturegrrl/2008/03/brooklynmurakamivuitton_it_kee.html

tsg

girvin.com