Rem Koolhaas

A new vision in Dubai is an amalgam of the plain with the bold —

OMA & Rem Koolhaas

“Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas revealed his concept of “the generic city,” a sprawling metropolis of repetitive buildings centered on an airport and inhabited by a tribe of global nomads with few local loyalties. His argument was that in its profound sameness, the generic city was a more accurate reflection of contemporary urban reality than nostalgic visions of New York or Paris.” Nicolai Ouroussoff | NYTimes

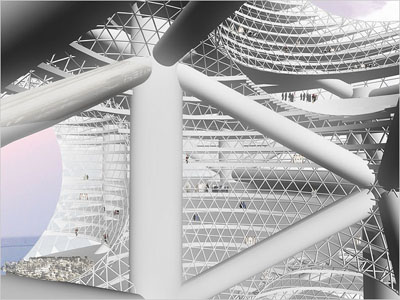

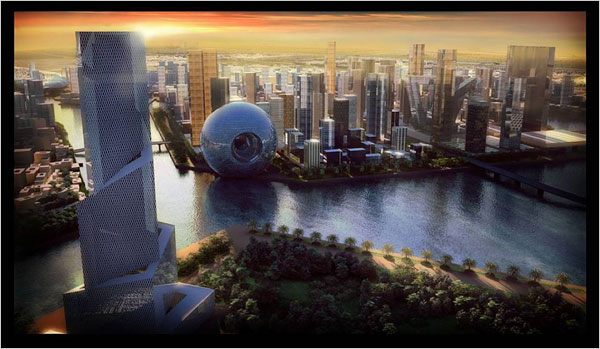

Koolhaas is on the edge of releasing the conceptions of the generic city, working for Narkheel, one of the largest developers in the UAR — and in this application a proposed island, man-made, 1.5 billion square feet — a Waterfront City, to be sited in off shore Dubai. According to the references, this would reflect the density of a city like Manhattan, situated just off shore in the Persian Gulf.

What I find challenging about this vision — the generic city applied — is the creation of a clustering of ill defined, simplistically nondescript towers juxtaposed with bold architectural gestures, that would, according to the NYTimes, “a center of urban experimentation as well as one of the world’s fastest growing metropolises.”

This mixed use applications, gigantic in scaled presence, are a statement. For Rem Koolhaas, the principle of design is about creating solutions for the mass urban intermingling of humanity. But his supposition is that the generic city is a contrast to the contrary, stylized environment of many other types of development. And architecture. And architects. The idea being that there are many development solutions that are merely egotistical gestures — the so-called Bilbao syndrome — expressing projects that are mere “theme parks” of architectural curiosities that mask the sense of sameness and homogeneity that lies beneath their structure.

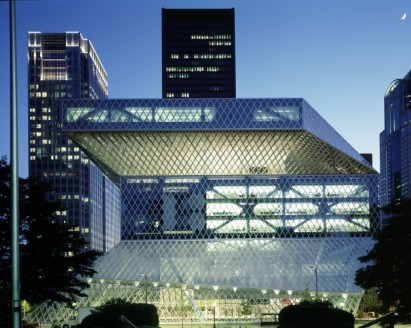

I question that. First, having studied the work of Koolhaas, I question the supposition that his work doesn’t in fact do the same thing. Just examining the dynamic power of the Seattle Library, there is much there to relate to the notion of creating a signature place, patterned distinctively. Comparing that to other Koolhaas work, you might suggest that there is a stylistic intention in his work, his colleagues at OMA. I’m not sure that others would intone the same character — but, look here:

http://oma.eu/projects/waterfront-city

Alliance Française | NL

Seattle Library US

Congress Hall | Lille FR

Educatorium | Utrecht NL

Back to the exploration of the generic city principles in Dubai.

The positioning of Koolhaas is neither linked distinctly to trendiness — in this project in offshore Dubai but instead to, as he puts it, find a kind of inevitable optimism in place. I’m not sure what that means. But the work, in plan, attempts to show off wild fantastic design, coupled with the generic. So the theory shows in one attribute and is lessened, contradicted in another. I’m not sure how that works.

The development core would be a square island, divided into 25 identical blocks — inserted here, a rhythmic display of towers.

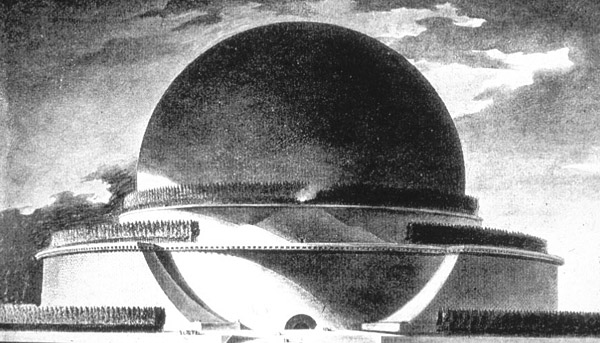

The rhythmic character of the structures, whose immense scale and formal energy, draw on mythic examples from architectural history. As noted in the Times, “A spiraling 82-story tower might have been inspired by the minaret of the ninth-century Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq; a gargantuan 44-story sphere brings to mind the symbolic forms of the 18th-century architect Étienne-Louis Boullée.” I made that recollection — in Boullée’s Newton Temple proposed by that visionary architect:

Others have commented on, in this application –“Mr. Koolhaas’s customary flair for composition. The gigantic sphere is placed precariously at the water’s edge, setting the entire ensemble artfully off balance.” There’s another point to the positioning — the slightly isolationist character of the emerging Dubai culture, a world of the profoundly rich, isolated in towers, surrounding the rest of the “fortress”.

“Whatever his social goals, Mr. Koolhaas will have little control over the makeup of this community, which, if current development in waterfront Dubai is any indication, is still likely to serve a small wealthy elite.

Then there is the question of scale. Covering six and a half square miles, the island is roughly the size of a small urban neighborhood. Is this large enough to sustain the dense social fabric that Mr. Koolhaas is after? Or is it more likely to become a new species of gated enclave, architecturally stupendous yet profoundly exclusionary? Does its compact size make it easier to seal off from supposed undesirables?”

The thrust of his strategy is “to turn the logic of the gated community on its head” and isolationist positioning that becomes a way to capture the energy of the city, rather than a barrier to entry. Will, however, the waterfront enclave be energized with the complexity to provide “a distilled version of the great metropolis within this moated sanctuary.” My point is really about place (referencing again another note and commentary from my friend Paula Rees — to place) https://www.girvin.com/blog/the-oed-brandish-brand-as-fire/.

The point to the query? The rather contrary nature of the Koolhaas’ notion of the generic and generalized experience of design of places, contrasted with the concept of environments that are detailed, rich and humane. Of course, city design is city design — urban | urbane, things are new, feel new. That’s nice. And personally, to my take, in traveling the channels of city expression around the world, I’ll go for something detailed, crowded, messy and rife with the scents of the human place, detailed in beauty — perhaps a little rough. But it’s truer. It’s more whole, more human. And that’s what I find myself pondering in the character of Koolhaas’ theoretical — and now perhaps realizable potential in Dubai. The other intriguing part of this puzzle is the balance between what might be generic, and what might be more, well, less generalized.

Here’s Koolhaas’ quote on this front — an interesting disposition:

Generic city’, a critic to current mode of urbanization: “People can inhabit anything. And they can be miserable in anything and ecstatic in anything. More and more I think that architecture has nothing to do with it. Of course, that’s both liberating and alarming. But the generic city, the general urban condition, is happening everywhere, and just the fact that it occurs in such enormous quantities must mean that it’s habitable. Architecture can’t do anything that the culture doesn’t. We all complain that we are confronted by urban environments that are completely similar. We say we want to create beauty, identity, quality, singularity. And yet, maybe in truth these cities that we have are desired. Maybe their very characterlessness provides the best context for living.” —interview in Wired 4.07, July 1996 [27]

Comments closed.

What’s your take?

Tim Girvin | Decatur Island