Ermenegildo Zegna’s Vellus Aureum

Luxury strategies and authentic truth. Making things by hand is a disappearing legacy. And even to the concept of the most luxurious, the idea of an object being completely handmade is a vanishing tradition. The concept of design and the handmade — one, being a “designer,” and another being a maker are elements that are achieving a kind of discrete distant from each other. Guy Salter, who I met in Palm Beach, at the American Express Luxury Summit, is the deputy chairman of Walpole, the luxury industry management trade association in the UK and spokesman for the alliance, said the loss of skills was a big concern. “All young people want to be designers and very few, makers. We want to try to change that by promoting craftsmanship in the luxury sector,” he said.

Costly skilled labor and the strong euro have pushed companies to source production from Asia and eastern Europe even though the imprimatur of an established producer in France or Italy is seen as essential to the high price tags. And, in some instances, while the label says “Made in France” — that is merely the branding, not the provenance.

In the UK alone, the tradition of craft in making brands by hand is dissipating at an accelerated pacing, according to Salter’s review, “Britain had only a “handful” of small factories making leather accessories, compared with more than 100 about 50 years ago.” Meanwhile, in France, the government is pushing the larger luxury groups to sign a charter of good practice this month to place more orders with national suppliers. This testament to vanishing authenticity in luxury is telling, given the extent of Dana Thomas‘ 2007 carefully researched overview of luxury’s failure in the truthful authenticity in the legacy of cost to value, precision to multiplicity:

“Back in the late 1980s, the Prada backpack — made out of black or tobacco-brown parachute fabric trimmed in leather — became the “it” bag for many would-be fashionistas. It was hip, modern, lightweight and at $450 expensive, but not as expensive as the stratospherically priced bags made by Hermès and Chanel. According to the fashion reporter Dana Thomas, that Prada backpack was also “the emblem of the radical change that luxury was undergoing at the time: the shift from small family businesses of beautifully handcrafted goods to global corporations selling to the middle market” — a shift from exclusivity to accessibility, from an emphasis on tradition and quality to an emphasis on growth and branding and profits.” (Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times) Ms. Thomas concludes, “It has realigned our economic class system. It has changed the way we interact with others. It has become part of our social fabric. To achieve this, it has sacrificed its integrity, undermined its products, tarnished its history and hoodwinked its consumers. In order to make luxury ‘accessible,’ tycoons have stripped away all that has made it special. And indeed, “Luxury has lost its luster.” [Thomas, Dana. Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster]

Confection Rousseau, with a staff of 47 in Vierzon, central France, focuses on the specialization of the cutting and stitching thick fabrics, and counted Christian Lacroix among its customers until the designer went into bankruptcy in 2009. Marc Rousseau, company founder, said: “I want the large luxury companies to answer the question: is it necessary to preserve manufacturing and savoir-faire in France? My fear is that these companies are happy to sell through the use of marketing and celebrities and that they don’t care about quality any more. So there is a real threat.”

Girvin’s studied the human brand components of the brand strategy of Hermés, one of the few brands left in France to truly embody the legacy of precise authenticity. Scheherazade Daneshkhu in Paris (The Financial Times), notes, “the Pantin factory in one of Paris’ rougher neighbourhoods, a row of craftspeople are stitching butter-soft leather bags with both their hands moving in a flamboyant cross-over manoeuvre.”

Hermès, the French luxury goods group that owns the factory, claims the double-stitching is the reason why its famed Kelly and Birkin handbags have the longevity to be passed on from mother to daughter. It takes a craftsperson four years of training to acquire the technique, which is one reason why Hermès can charge at least €5,000 ($6,750, £4,400) a bag. While Hermès has increased its craftsmen in the last 10 years from 300 to 2,000 to satisfy rising demand, the trend across France is the opposite.”

“France must fight not to lose its savoir-faire, its skills and high-quality expertise even if developing countries have the right to produce,” Segolène Royal, the former Socialist presidential candidate, told the Made in France trade show earlier this year.

All this lends itself to the concept of being true — finding the heart of the brand — doing what is necessary to preserve the tradition, whatever that might be. Perhaps, to luxury, this is all about the hand. In speaking to Shirin Von Wulffen, formerly at Yves Saint Laurent, when I worked with her, then later at Tom Ford, we talked about this, the idea of the hand made; this tradition lies at the soul of everything that Tom Ford does. That sense of craft lies in the center of his legacy — before Tom Ford, Gucci and YSL, and then in the building of his own brand.

“A great family makes a great company, a great company makes a great family.” Gildo Zegna

Zegna is another, that speaks to this tradition — the hand. Their site explains more, to the legacy: “Zegna immediately conjures up two inseparable realities. On one hand, one of the oldest families of entrepreneurs in Italy, its fourth generation currently leading the company, and on the other a leading multinational company in the men’s luxury clothing industry, distributing its products in over 80 countries worldwide and generating over 88% of its sales overseas, with powerful operations in both mature and emerging markets.”

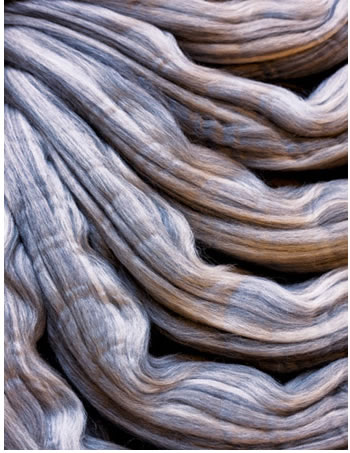

To make the finest suit in the world, Zegna is seeking out, and awarding, the finest collection of wool on the planet. Hence, Ermenegildo Zegna’s Vellus Aureum Award, an annual contest to locate the highest quality merino wool that can be found. The “Golden Fleece” will entitle the recipient awardee the weight of the fleece in gold.

To timing, the program to identify the finest wool in the world, was first awarded in 2001. The Trophy, currently contended by Australian, New Zealand and South Africa producers, is restricted to fleeces with a fineness of under 13.9 micron. According to the NYTimes, Zegna is “celebrating its 100-year anniversary, Zegna has woven together samples of the competition’s top fleeces since 2002 to create one of the lightest fabrics ever worn: the lot’s fibers measure 11.1 microns on average, while a human hair averages a whopping 100 microns. Obviously limited by supply (only about 200 feet of cloth is produced) to an edition of 20 and retailing at $22,500, each made-to-order Centennial Vellus Aureum suit takes 18-plus hours to create and passes through more than 330 pairs of hands. ‘‘Is this the ultimate in men’s-wear luxury?’’ Anna Zegna, the image director of the brand, asks rhetorically. ‘Oh, we certainly think so.'”

Some imagery and storytelling, to support the proposition:

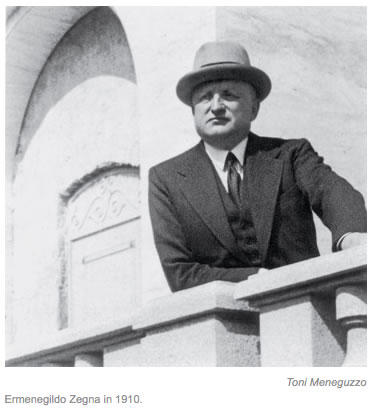

The Zegna fabric mill, in 1910, which moved into men’s wear in the 1960s. Founded by Emenegildo Zegna, the legacy continues with his sons, Angelo and Aldo. Near the family home, the wool mill is run in the small town of Trivero, in the Italian Alps.

Inside the mill, the winning golden fleece awarded wool is spun, separated and then recombined as yarn in a manner that reaches back to the 18th century. Dyed to specification they are stored in battered beech trunks manufactured in the early 20th century.

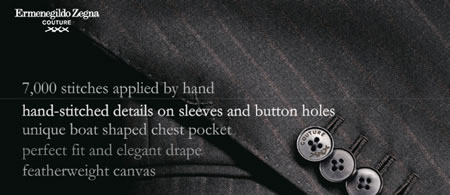

After cutting in Zegna’s factory in Stabio, Switzerland, the fabric arrives in six core pieces at the couture works in Padua, Italy. A 140-step, sequenced construction process begins with stitching the inner layers of canvas — horsehair, goat hair and flannel to the front of the jacket. From there, every piece is then worked by hand, first with placement stitching or basting, then replaced with permanet sswing. There is only one automated machine in the factory, used to cut out the winglets for the breast pocket.

The jacket is a proposition of slow tailoring — every aspect of every operation is carefully checked and rechecked, and meticulously ironed. The master tailors attach the sleeves and the collar, requiring the most precision in the delicacy of the application. Buttonholes are sewn by hand, as are the distinctive labeling and arrow-stitching. The last of the suit details in the 33,000 stitches is a single “stemholder” stitch behind the label itself.

All of the photographs in the above sequence of images are by Toni Meneguzzo.

Not everything can be done by hand, but there are traditions of attention to detail — the slow luxury — that are linked to the highest craft, laden with incipient value, that boost the character of the product. Time tells. Value deepens. In the emergence of increasingly accelerated product development, faster turn cycles, grab and go acquisition, pricing as the only option, there is something in the meditation on the beauty of something carefully crafted and beautifully made — something which might be, even…passed along.

tsg

….

Building luxury brands

Girvin & luxury brand patterning

the reels: http://www.youtube.com/user/GIRVIN888

girvin blogs:

http://blog.girvin.com/

https://tim.girvin.com/index.php

girvin profiles and communities:

TED: http://www.ted.com/index.php/profiles/view/id/825

Behance: http://www.behance.net/GIRVIN-Branding

Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tgirvin/

Google: http://www.google.com/profiles/timgirvin

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/timgirvin

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/people/Tim-Girvin/644114347

Facebook Page: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Seattle-WA/GIRVIN/91069489624

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tgirvin