Explorations on color, meaning and experience. And Michelle.

Surely I can’t offer an presentment on the concept of the implication of color , the symbolism, let alone the depth of experience that exists in the trade on color trending — and the shifts, year to year, that captivate the market. Or anything other than personal reflections on what the color yellow might represent in the making of place.

There’s plenty of content out there on that front, by experts far greater than I.

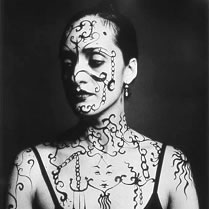

Photo: Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

But Michelle, as she’ll be known from this point outwards, the First Lady, has brought the concept of optimism in presentation to a new front.

But what about just one color, and the intimations that might be found there? A lot. With nearly any word, I go back, look in, look deep. When you examine the heart of a word, that etymon, there is a layering of content that’s meaningful. At least for me, that’s the way it works. Study the network of meaning, and frame the tapestry of content. Here’s a string to an etymological spread of ideas — and implications:

yellow

O.E. geolu, geolwe, from P.Gmc. *gelwaz (cf. O.S., O.H.G. gelo, M.Du. ghele, Du. geel, M.H.G. gel, Ger. gelb, O.N. gulr, Swed. gul “yellow”), from PIE *ghel-/*ghol- “yellow, green” (see Chloe — below). The verb meaning “to become yellow” is O.E. geoluwian. Adj. meaning “light-skinned” (of blacks) first recorded 1808. Applied to Asiatics since 1787, though the first recorded reference is to Turkish words for inhabitants of India. Yellow peril translates Ger. die gelbe gefahr. The sense of “cowardly” is 1856, of unknown origin; the color was traditionally associated rather with treachery. Yellow-bellied “cowardly” is from 1924, probably a rhyming reduplication of yellow; earlier yellow-belly was a sailor’s name for a half-caste (1867) and a Texas term for Mexican soldiers (1842, based on the color of their uniforms). Yellow dog “mongrel” is attested from c.1770; slang sense of “contemptible person” first recorded 1881.

yellow journalism

“sensational chauvinism in the media,” 1898, Amer.Eng. from newspaper agitation for war with Spain; originally “publicity stunt use of colored ink” (1895) in ref. to the popular Yellow Kid”character (his clothes were yellow) in Richard Outcault’s comic strip “Shantytown” in the “New York World.”

yellow ribbon

The American folk custom of wearing or displaying a yellow ribbon to signify solidarity with loved ones or fellow citizens at war originated during the U.S. embassy hostage crisis in Iran in 1979. It does not have a connection to the American Civil War, beyond the use of the old British folk song “Round Her Neck She Wore A Yellow Ribbon” in the John Wayne movie of the same name, with a Civil War setting, released in 1949. The story of a ribbon tied to a tree as a signal to a convict returning home that his loved ones have forgiven him is attested from 1959, but the ribbon in that case was white. The ribbon color seems to have changed to yellow first in a version retold by newspaper columnist Pete Hamill in 1971. The story was dramatized in June 1972 on ABC-TV (James Earl Jones played the ex-con). Later that year, Irwin Levine and L. Russell Brown copyrighted the song “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” which became a pop hit in early 1973 and sparked a lawsuit by Hamill, later dropped. In 1975, the wife of a Watergate conspirator put out yellow ribbons when her husband was released from jail, and news coverage of that was noted and remembered by Penne Laingen, whose husband was U.S. ambassador to Iran in 1979 and one of the Iran hostages taken in the embassy on Nov. 4. Her yellow ribbon in his honor was written up in the Dec. 10, 1979, “Washington Post.” When the hostage families organized as the Family Liaison Action Group (FLAG), they took the yellow ribbon as their symbol. The ribbons revived in the 1991 Gulf War and again during the 2003 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Chloe

fem. proper name, from Gk. Khloe, lit. “young green shoot;” related to khloros “greenish-yellow,” from PIE *ghlo- var. of base *ghel-, a color word that has yielded words for both “yellow” (cf. L. helvus “yellowish, bay,” Gallo-L. gilvus “light bay;” Lith. geltonas “yellow;” O.C.S. zlutu, Pol. zolty, Rus. zeltyj “yellow;” Skt. harih “yellow, tawny yellow,” hiranyam “gold;” Avestan zari “yellow;” O.E. geolu, geolwe, Mod. Eng. yellow, Ger. gelb “yellow”) and “green” (cf. L. galbus “greenish-yellow;” Gk. khloros “greenish-yellow color,” kholos “bile;” Lith. zalias “green,” zelvas “greenish;” O.C.S. zelenu, Pol. zielony, Rus. zelenyj “green;” O.Ir. glass, Welsh, Breton glas “green,” also “grey, blue”). Buck says the interchange of words for yellow and green is “perhaps because they were applied to vegetation like grass, cereals, etc., which changed from green to yellow.” It is possible that this whole group of yellow-green words is related to PIE base *ghlei- “to shine, glitter, glow, be warm” (see gleam).

jaundice

c.1303, from O.Fr. jaunisse “yellowness” (12c.), from jaune “yellow,” from L. galbinus “greenish yellow,” probably from PIE *ghel- “yellow, green” (see Chloe). With intrusive -d- (cf. gender, astound, thunder). Meaning “feeling in which views are colored or distorted” first recorded 1629, from yellow’s association with bitterness and envy (see yellow).

yolk

O.E. geolca, geoloca “yolk,” lit. “the yellow part,” from geolu “yellow” (see yellow). Formerly also spelled yelk.

xanthous

1829, from Gk. xanthos “yellow,” of unknown origin. Prefix form xantho- is used in many scientific words; cf. xanthein (1857) “soluble yellow coloring matter in flowers,” Huxley’s Xanthochroi (1867) “blond, light-skinned races of Europe” (with okhros “pale”), xanthophyll (1838) “yellow coloring matter in autumn leaves.”

Flavius

male proper name, from L. Flavius, a Roman gens name, related to flavus “yellow” (see blue), and probably originally meaning “yellow-haired.”

ochre

1398, “type of clayey soil (much used in pigments),” from O.Fr. ocre (1307), from L. ochra, from Gk. ochra, from ochros “pale yellow,” of unknown origin. As a color name, “brownish-yellow,” it is attested from c.1440.

amarillo

name given to several species of Amer. trees, from Sp., from Arabic anbari “yellow, amber-colored,” from anbar “amber,” probably from L. amarus “bitter,” “through application to some bitter (yellow) substance, such as gall” [Buck]. The city Amarillo in Texas, U.S., may be so called from the color of the banks of a nearby stream.

bay

“reddish-brown,” 1341, from Anglo-Fr. bai, from O.Fr. bai, from L. badius “chestnut-brown” (used only of horses), from PIE *badyo- “yellow, brown” (cf. O.Ir. buide “yellow”). Also elliptical for a horse of this color.

gall

“bile,” O.E. galla (Anglian), gealla (W. Saxon), from P.Gmc. *gallon- (cf. O.N. gall, O.H.G. galla), from PIE base *ghol-/*ghel- “gold, yellow, yellowish-green” (cf. Gk. khole, see cholera; L. fel; perhaps also O.E. geolo “yellow,” Gk. khloros). Informal sense of “impudence, boldness” first recorded Amer.Eng. 1882; but meaning “embittered spirit, rancor” is from c.1200.

blond

1481, from O.Fr. blont, from M.L. adj. blundus “yellow,” perhaps from Frank. *blund. If it is a Gmc. word, possibly related to O.E. blonden-feax “gray-haired,” from blondan, blandan “to mix” (see blend). According to Littré, the original sense of the Fr. word was “a colour midway between golden and light chestnut,” which might account for the notion of “mixed.” O.E. beblonden meant “dyed,” so it is also possible that the root meaning of blonde, if it is Gmc., may be “dyed,” as the ancient Teutonic warriors were noted for dying their hair. Du Cange, however, writes that blundus was a vulgar pronunciation of L. flavus “yellow.” The word was reintroduced into Eng. 17c. from Fr., and was until recently still felt as Fr., hence blonde for females. As a noun, used c.1755 of a type of lace, 1822 of people.

electrum

“alloy of gold and silver,” 1398 (in O.E. elehtre), from L., lit. “amber,” so called probably for its pale yellow color.

glass

O.E. glæs, from W.Gmc. *glasam (cf. M.Du. glas, Ger. Glas), from P.Gmc. base *gla-/*gle-, from PIE *gel-/*ghel- “to shine, glitter, be green or yellow,” a color word that is the root of words for grey, blue, green, and yellow (cf. O.E. glær “amber,” L. glaesum “amber,” O.Ir. glass “green, blue, gray,” Welsh glas “blue”). Sense of “drinking glass” is c.1225; glasses for “spectacles” is 1660s. The glass slipper in “Cinderella” is probably an error by Charles Perrault, translating in 1697, mistaking O.Fr. voir “ermine, fur” for verre “glass.” In other versions of the tale it is a fur slipper.

Glass ceiling first recorded 1990.

cirrhosis

1840s, coined by Fr. physician René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec (1781-1826), from Gk. kirrhos “tawny,” for the orange-yellow appearance of the diseased liver.

blue

c.1300, bleu, blwe, etc., from O.Fr. bleu, from Frank. blao, from P.Gmc. *blæwaz, from PIE base *bhle-was “light-colored, blue, blond, yellow.” “The exact color to which the Gmc. term applies varies in the older dialects; M.H.G. bla is also “yellow,” whereas the Scandinavian words may refer esp. to a deep, swarthy black, e.g. O.N. blamaðr, N.Icel. blamaður ‘Negro’ ” [Buck]. Replaced O.E. blaw, from the same PIE root, which also yielded L. flavus “yellow,” O.Sp. blavo “yellowish-gray,” Gk. phalos “white,” Welsh blawr “gray,” O.N. bla “livid” (the meaning in black and blue), showing the usual slippery definition of color words in I.E. The present spelling is since 16c., from Fr. influence. The color of constancy since Chaucer at least, but apparently for no deeper reason than the rhyme in true blue (1500). Blue (adj.) “lewd” is recorded from 1840; the sense connection is unclear, and is opposite to that in blue laws (q.v.). Blueprint is from 1886; the fig. sense of “detailed plan” is first attested 1926. For blue ribbon, see cordon bleu under cordon. Blue moon emblematic of “very rarely” suggests something that, in fact, never happens (cf. at the Greek calends), as in this couplet from 1528:

Yf they say the mone is blewe,

We must beleve that it is true.

Many IE languages seem to have had a word to describe the color of the sea, encompasing blue and green and gray; e.g. Ir. glass (see Chloe), O.E. hæwen “blue, gray,” related to har (see hoar), Serbo-Cr. sinji “gray-blue, sea-green,” Lith. šyvas, Rus. sivyj “gray.”

buttercup

type of small wildflower with a yellow bloom, 1777, from a merger of two older names, gold-cups and butterflower.

Boyd

in many cases, the family name represents Gaelic or Irish buidhe “yellow,” suggesting blond hair, cf. Manx name Mac Giolla Buidhe (1100).

lurid

1656, from L. luridus “pale yellow, ghastly,” of uncertain origin, perhaps cognate with Gk. khloros (see Chloe). The figurative sense of “sensational” is first attested 1850.

Xanthippe

1596, spouse of Socrates (5c. B.C.E.), the prototype of the quarrelsome, nagging wife. The name is related to the masc. proper name Xanthippos, a compound of xanthos “yellow” + hippos “horse.”

biretta

square cap worn by Catholic clergy, 1598, from It. beretta, from L.L. birrus, birrum “large cloak with hood, perhaps of Gaulish origin, or from Gk. pyrros “flame-colored, yellow.”

natterjack

1769, rare kind of toad with a yellow stripe on its back; second element probably proper name jack (q.v.); for first element, Weekley suggests connection with attor “poison” (cf. attercop).

tawny

“tan-colored,” 1377, from Anglo-Fr. tauné “associated with the brownish-yellow of tanned leather,” from O.Fr. tané (12c.), pp. of taner “to tan hides,” from M.L. tannare (see tan).

Isabel

a form of Elizabeth that seems to have developed in Provence. A popular name in Middle Ages; pet forms included Ibb, Libbe, Nibb, Tibb, Bibby, and Ellice. The Sp. form was Isabella, which is attested as a color name (“greyish-yellow”) from 1600; the Isabella who gave her name to it has not been identified.

jonquil

1629, species of narcissus, from Fr. jonquille, from Sp. junquillo, dim. of junco “rush, reed,” from L. juncus “rush;” so called in reference to its leaves. The type of canary bird (1865) is so called for its pale yellow color, which is like that of the flower.

yarrow

plant, also known as milfoil, O.E. gearwe, from P.Gmc. *garwo (cf. M.Du. garwe, O.H.G. garawa, Ger. Garbe), perhaps from a source akin to the root of yellow.

off-white

“white with a tinge of gray or yellow,” 1927, from off + white.

weld

plant (Resedo luteola) producing yellow dye, c.1374, from O.E. *wealde, perhaps a variant of O.E. wald “forest” (cf. M.L.G. walde, M.Du. woude). Sp. gualda, Fr. gaude are Gmc. loan-words.

panther

c.1220, from O.Fr. pantere (12c.), from L. panthera, from Gk. panther, probably of Oriental origin, cf. Skt. pundarikam “tiger,” probably lit. “the yellowish animal,” from pandarah “whitish-yellow.” Folk etymology derivation from Gk. pan- “all” + ther “beast” led to many curious fables.

oriole

1776, from Fr. oriol, O.Prov. auriol, from L. aureolus “golden,” from PIE *aus- “gold.” Originally in ref. to the Golden Oriole (Oriolus galbula), a bird of black and yellow plumage that summers in Europe (but is uncommon in England). Applied from 1791 to the unrelated but similarly colored Amer. species Icterus baltimore.

mellow

c.1440, melwe, “soft, sweet, juicy” (of ripe fruit), perhaps related to melowe, var. of mele “ground grain” (see meal (2)), infl. by M.E. merow “soft, tender,” from O.E. mearu. Meaning “slightly drunk” is from 1690. The verb is from 1572. Mellow yellow “banana peel smoked to get high” is from 1967.

plumbago

“graphite,” 1784, from L. plumbago “a type of lead ore, black lead,” from plumbum “lead” (see plumb); it renders Gk. molybdaina, which was used of yellow lead oxide and also of a type of plant.

crocus

1398, from L. crocus, from Gk. krokos “saffron, crocus,” probably of Sem. origin (cf. Arab kurkum), ult. from Skt. kunkumam. The autumnal crocus (Crocus sativa) was a common source of yellow dye in Roman times, and was perhaps grown in England, where the word existed as O.E. croh, but this form of the word was forgotten by the time the plant was re-introduced in Western Europe by the Crusaders.

Goldilocks

name for a person with bright yellow hair, 1550, from adj. form of gold + lock in the hair sense. The story of the Three Bears first was printed in Robert Southey’s miscellany “The Doctor” (1837), but the central figure there was a bad-tempered old woman. Southey did not claim to have invented the story, and older versions have been traced, either involving an old woman or a “silver-haired” girl (though in at least one version it is a fox who enters the house). The naming of the girl as Goldilocks is only attested from c.1904.

yew

O.E. iw, eow “yew,” from P.Gmc. *iwa-/*iwo- (cf. M.Du. iwe, Du. ijf, O.H.G. iwa, Ger. Eibe, O.N. yr), from PIE *ei-wo- (cf. O.Ir. eo, Welsh ywen “yew”), perhaps a suffixed form of *ei- “reddish, motley, yellow.” OED says Fr. if, Sp. iva, M.L. ivus are from Gmc. (and says Du. ijf is from Fr.); others posit a Gaul. ivos as the source of these. Lith. jeva likewise is said to be from Gmc. It symbolizes both death and immortality, being poisonous as well as long-lived.

riboflavin

1935, from Ger. Riboflavin (1935), from ribose (q.v.) + flavin, from L. flavus “yellow” (see blue), so called from its color.

amber

1365, “ambergris,” from O.Fr. ambre, from M.L. ambar, from Arabic ‘anbar “amber,” a word brought home to Europe by the Crusaders. The sense was extended to fossil resin c.1400, which has become the main sense as the use of ambergris has waned. This was formerly known as white or yellow amber. In Fr., they are distinguished as ambre gris and amber jaune. Cf. also electric.

arsenic

c.1386, from O.Fr. arsenic, from L. arsenicum, from Gk. arsenikon “arsenic,” adopted for Syriac (al) zarniqa “arsenic,” from Middle Persian zarnik “gold-colored” (arsenic trisulphide has a lemon-yellow color). The Gk. word is folk etymology, from arsen “male, strong, virile” (cf. arseno-koites “lying with men” in N.T.) supposedly in reference to the powerful properties of the substance. The mineral (as opposed to the element) is properly orpiment, from L. auri pigmentum, so called because it was used to make golden dyes.

gullible

1793 (implied in gullibility), earlier cullibility (1728), probably connected to gull, a cant term for “dupe, sucker” (1594), which is of uncertain origin. It is perhaps from the bird (see gull (n.)), or from verb gull “to swallow” (1530, from O.Fr. goule, from L. gula “throat,” see gullet); in either case with a sense of “someone who will swallow anything thrown at him.” Another possibility is M.E. dial. gull “newly hatched bird” (1382), which is perhaps from O.N. golr “yellow,” from the hue of its down.

sallow

O.E. salo “dusky, dark” (related to sol “dark, dirty”), from P.Gmc. *salwa- (cf. M.Du. salu “discolored, dirty,” O.H.G. salo “dirty gray,” O.N. sölr “dirty yellow”), from PIE base *sal- “dirty, gray” (cf. O.C.S. slavojocije “grayish-blue color,” Rus. solovoj “cream-colored”).

pallor

c.1400, from O.Fr. palor “paleness,” from L. pallor, from pallere “be pale,” related to pallus “dark-colored, dusky,” from PIE base *pel- “dark-colored, gray” (cf. Skt. palitah “gray,” panduh “whitish, pale,” Gk. pelios “livid,” polios “gray,” O.E. fealo “dull-colored, yellow, brown”).

flesh

O.E. flæsc “flesh, meat,” also “near kindred” (a sense now obsolete except in phrase flesh and blood), common W. and N.Gmc. (cf. O.Fris. flesk, M.L.G. vlees, Ger. Fleisch “flesh,” O.N. flesk “pork, bacon”), of unknown origin, perhaps from P.Gmc. *flaiskoz-. Figurative use for “animal or physical nature of man” (O.E.), is from the Bible, especially Paul’s use of Gk. sarx, which yielded sense of “sensual appetites” (c.1200). Fleshpot is lit. “pot in which flesh is boiled,” hence “luxuries regarded with envy,” especially in fleshpots of Egypt, from Exodus xvi.3:

“Whan we sat by ye Flesh pottes, and had bred ynough to eate.” [Coverdale translation, 1535]

Flesh-wound is from 1674; flesh-color, the hue of “Caucasian” skin, is first recorded 1611, described as a tint composed of “a light pink with a little yellow” [O’Neill, “Dyeing,” 1862]. Fleshy “plump” is from c.1369. An O.E. poetry-word for “body” was flæsc-hama, lit. “flesh-home.”

butterfly

O.E. buttorfleoge, perhaps based on the old notion that the insects (or witches disguised as butterflies) consume butter or milk that is left uncovered. Or, less creatively, simply because the pale yellow color of many species’ wings suggests the color of butter. Another theory connects it to the color of the insect’s excrement, based on Du. cognate boterschijte. A fascinating overview of words for “butterfly” in various languages can be found here. The swimming stroke so called from 1936. Butterflies “light stomach spasms caused by anxiety” is from 1908.

The butterfly effect is a deceptively simple insight extracted from a complex modern field. As a low-profile assistant professor in MIT’s department of meteorology in 1961, [Edward] Lorenz created an early computer program to simulate weather. One day he changed one of a dozen numbers representing atmospheric conditions, from .506127 to .506. That tiny alteration utterly transformed his long-term forecast, a point Lorenz amplified in his 1972 paper, “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” [Peter Dizikes, “The Meaning of the Butterfly,” The Boston Globe, June 8, 2008]

gold

O.E. gold, from P.Gmc. *gulth- (cf. O.S., O.Fris., O.H.G. gold, Ger. Gold, M.Du. gout, Du. goud, O.N. gull, Dan. guld, Goth. gulþ), from PIE base *ghel-/*ghol- “yellow, green,” possibly ult. “bright” (cf. O.C.S. zlato, Rus. zoloto, Skt. hiranyam, O.Pers. daraniya-, Avestan zaranya- “gold;” see Chloe). In reference to the color of the metal, it is recorded from c.1400. Golden replaced M.E. gilden, from O.E. gyldan. Gold is one of the few Mod.Eng. nouns that form adjs. meaning “made of ______” by adding -en (e.g. wooden, leaden, waxen, olden); O.E. also had silfren “made of silver,” stænen “made of stone.” Goldenrod is 1568; goldfinch is from O.E. goldfinc; goldfish is from 1698, introduced into England from China, where they are native. Gold-digger “woman who pursues men for their money,” first recorded 1915. Goldbrick (n.) “shirker” (1914) is World War I armed forces slang, from earlier verb meaning “to swindle, cheat” (1902) from the old con game of selling spurious “gold” bricks. Golden mean “avoidance of excess” translates L. aurea mediocritas (Horace). Golden rule (originally Golden law) so called from 1674.

“Do not do unto others as you would that they should do unto you. Their tastes may not be the same.” [George Bernard Shaw, 1898]

In exploring the idea of color — and the string of ideas that spring from that one countenance, it’s a powerful threading of experiences — from sublime beauty, to potent poisons, from valuable stones, to flowers, herbs and the “colors” of people. And it’s all about that — seeing color. But yellow is special — it’s especially rich — and almost richer than any other word that I can find about color. Except, of course, red. And it’s extraordinary that there are so many words, ancient and otherwise, linked to the concept of one type of color experience. Meaning that yellow is a color value experience that happens because of a certain refraction of light, molecules and time — and in that way of seeing, it’s merely part of the spectrum of visual content.

But the symbolic power of the optimism in color is especially dramatic, given the challenges of our times — elements of difficulty that nearly every person in America is touched by. Moreover, the world. This palette treatment, that is expressed in Michelle Obama’s ensemble, was created by Isabel Toledo, the Cuban-born designer of Mrs. Obama’s inaugural outfit.” She commented that she did not know positively until the morning of the event if the new first lady would wear the lemongrass-yellow coat and matching dress she specially designed for her. “We’re all up here watching the T.V.,” said the designer in a telephone interview from her New York studio. “It’s great. We’re so happy.”

According to Cathy Horyn, “Ms. Toledo, who has been making clothes in New York for 25 years, said the coat and dress were made of Swiss wool lace, backed with netting for warmth and lined in French silk. “I wanted to pick a very optimistic color, that had sunshine,” she said. “I wanted her to feel charmed, and in that way would charm everybody.” Ms. Toledo sounded overwhelmed. “This is so wonderful,” she said.”

Toledo, who’s the wife of designer and illustrator Ruben Toledo, the current illustrative reference for all creative at Nordstrom, said that about thirteen people in her studio worked on the outfit over the Christmas holidays. “Chinese ladies, Polish ladies, Spanish ladies—I have a picture of everyone working on her clothes,” Ms. Toledo, who is 48, said. She added, “We’re all grateful for this opportunity, and we don’t even have a PR person!”

Like the other designers who have made inaugural clothes for Mrs. Obama, Ms. Toledo worked with Ikram Goldman, the owner of a boutique in Chicago called Ikram, where Mrs. Obama has previously bought clothes. Ikram also sells clothes by Narciso Rodriguez and Maria Cornejo, other favored designers of Michelle Obama.

Color is psychically deep — in its ability to captivate, and capture the expression of experience — it is a nearly indefinable, ineffable quality. It’s emotional — it’s instantly reactive and inciting. We see color and respond instantly — often times, not even knowingly. And emotionally, we connect with yellow because it’s about the Sun — it’s the entablature of how all light seemingly works; it’s the stream that feels like it makes other colors real. It’s the embodiment of living light. And that’s what we need. Light. Energy. Golden healing. Health vibrancy.

Michelle seems to have thought that through. Or, instinctually, she’s said — this is what I need to say to the people. She’s clearly linked in, resolutely throwing open, flinging wide, the doors of The White House. To hope.

Personally, I can relate to that path to light. And, being a leader among leaders, she’s out in front about the presence of her sentiments.

What about you and yellow?

tsg | NYC

—-

References:

Doug Mills/The New York Times

What about the concept of the colors, themselves — how does the color work? What’s it come from? Where does yellow derive it’s compelling power?

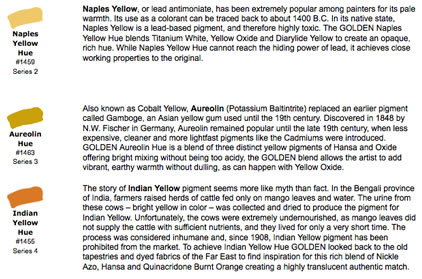

Color Analyses |YELLOWS:

Orpiment: Pigment of Gold. It was said that it can only be lightened with white from calcined hartshorn, NOT with white lead as commonly used. (see pigment chemistry page) There are two arsenic yellows called “yellow orpiment” (King’s Yellow or Royal Yellow: arsenic trisulfide) and “red orpiment” (Realgar or Risalgallo: arsenic disulfide). De Mayerne mentions that orpiment should not be touched with an iron knife. Later replaced by an artificial version known as King’s Yellow or Auripigmentum, a very bright, opaque yellow. Poisonous and not reliably permanent, having limited compatibility with other pigments. Used from the earliest civilizations and throughout the history of art until they were replaced by cadmiums.

Light and Brown Ochre: made of earth. Light ochre was used in flesh tones. Brown Ochre is a dull variety of yellow ochre (PY 43). The Romans called it Sil, with the finest grade coming from Greece called Attic sil.

Mars Yellow: rust of iron. (PY 42) Today it is factory-made iron hydroxide that usually resembles the tone of the natural earth yellows, such as yellow ocher or raw sienna. It is permanent.

Light and Dark Yellow Lake: vegetable based dyes impregnated upon chalk (white earth). Like all lakes, susceptible to fading. Yellow lake is an unstandardized term used for a number of transparent pigments today and is reliably substituted by Cobalt yellow (PY 40) and the Hansa Yellows (PY 1, 3, 65, 73, 74, or 98).

Massicot (Masticote): (lead tin yellow); Was thought at one time to be a monoxide of lead, but is deeper or more pinkish in hue than litharge. blackens in time and changes when exposed to the sun. Never was considered permanent. Cennini remarks that its tint was injured by much grinding. Italian writers referred to this as giallorino, giallolino, and giallolino de Fiandra.

There seems to be some confusion in literature as to the exact makeup of Massicot. Lead-tin yellow is said by some conservators to be similar in handling and properties to lead antimoniate. (see below – Naples Yellow)

Naples Yellow: Lead Antimoniate (PY 41)- poisonous. The true pigment is infrequently sold today. (check Pigements Present listing for retailers) Around 1700 Naples yellow began to replace the hitherto traditional yellow pigment, lead-tin yellow, and enjoyed its highest popularity between approximately 1750 and 1850. It was itself replaced by the barium chromates and cadmium sulphides. “There is no explanation for the disappearance of lead-tin yellow from the painter’s palettes and the replacement with lead antimonate. Lead-tin yellow can, dependent on component ratios and firing conditions, be made of an intense colour. Lead antimonate is often of a rather pale hue. Other wise, the working properties of both pigments are fairly similar. The production methods for Naples yellow are quite similar to those for lead-tin yellow (type I). In the production of Naples yellow the stannate component of lead-tin yellow was simply replaced by antimony.”

— Joris Dik / Arie Wallert

It is a useful color that has many of the characteristics of flake white, such as a rapid rate of drying and good film-forming properties. It shares the disadvantages of flake white — that is, it is toxic (but careful use prevents harm) and sensitive to sulfur (but can be protected from atmospheric pollutants by varnish and by avoiding combination with reactive sulfide pigments.(see pigment chemistry page) Modern substitutes sold under the name are usually mixtures of cadmium yellow, zinc white, and ocher. These dry more slowly and have an inferior film quality when compared to true Naples Yellow.

Lightfastness: I

Oil Absorption: Very Low

Oil Film: fast drying, tough, flexible

Toxicity: highly toxic, do not ingest, do not breathe dust

Saffron: An obsolete bright yellow color obtained from the dried petals of Crocus sativus. Fades badly in daylight. Used in Roman times.

Litharge: Lead monoxide. A heavy, yellowish powder (obsolete as a paint pigment) used as a drier when cooking resin-oil varnish mediums.

Mixtures: Yellows were mixed with Vermilion to make a nice golden orange. And transparent yellows were mixed with red browns to glaze in warm shadows over a light ground.

Golden pigment overview:

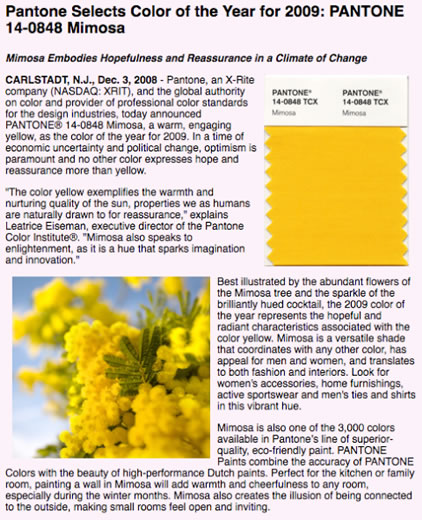

Pantone Color Trending | 2009