ROUGH TRADE #3

The Perfume of Refuse, Decomposition and Excrement

(The third of three essays on unusual scent strategies)

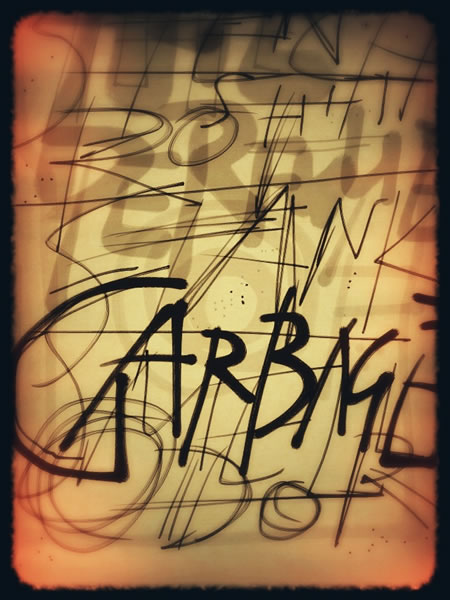

In the beginnings of Das Parfum, authored by Patrick Süskind, there is a grouping of expressions that I’d first read in the original German.

The opening of the story, telling “Perfume,” is about stank — the most offal smell. Trash, rot, excrement — the scenting of the 18th century Paris.

Translated, here — I was transfixed, carried there — the notes of this telling belie the miracle of the layering of mysterious scent; an evocation of the astonishment of smell wafting up from the mess of humanity:

“In the period of which we speak, there reigned in the cities a stench barely to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries, and from the slaughterhouses came from the stench of congealed blood. People stank of sweat and unwashed clothes; from their mouths came the stench of rotting teeth, from their bellies that of onions, and from their bodies, if they were no longer very young, came the stench of rancid cheese and sour milk and tumorous disease. The rivers stank, the marketplaces stank, the churches stank, it stank beneath the bridges and in the palaces. The peasant stank as did the priest, the apprentice as did the master’s wife, the whole of the aristocracy stank, even the king himself stank, stank like a rank lion, and the queen like an old goat, summer and winter. For in the eighteenth century there was nothing to hinder bacteria busy at decomposition, and so there was no human activity, either constructive or destructive, no manifestation of germinating or decaying life that was not accompanied by stench.

And of course the stench was foulest in Paris, for Paris was the largest city of France. And in turn there was a spot in Paris under the sway of a particularly fiendish stench, between the rue aux Fers and the rue de la Ferronnerie, the Cimetière des Innocents to be exact. For eight hundred years the dead had been brought here from the Hôtel-Dieu and the surrounding parish churches, for eight hundred year, day in, day out, corpses by the dozens had been carted here and tossed into long ditches, stacked bone upon bone for eight hundred years in the tombs and charnel houses. Only later — on the eve of the Revolution, after several of the grave pits caved in and the stench had driven the swollen graveyard’s neighbors to more than mere protest and to actual insurrection — was it finally closed and abandoned. Millions of bones and skulls were shoveled into the catacombs of Montmartre and in its place a food market was erected.

Here, then, on the most putrid spot in the whole kingdom, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille was born on July 17, 1738. It was one of the hottest days of the year. The heat lay leaden upon the graveyard, squeezing its putrefying vapor, a blend of rotting melon and the fetid odor of burnt animal horn, out into the nearby alleys.”

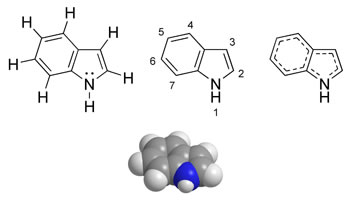

What possible connection could any of this have to do with the lofty arts of perfume? Firstly, the nature of the art is the layering of scents — and most of the evocative and unforgettable scents have deeper and darker notes — the animalic, the smoke of fat and burning wood and even, surprisingly, the indoles. According to scent master, Luca Turin, in “The Secret of Scent,” is probably the most unfairly maligned molecule [2] on earth.” While dirty in character, it’s also a commonly referenced deepest note for the creation of fragrances — because, perhaps, it is the most human. And unforgettable. That scent drops deep into the mind and memory of virtually anyone that has lived.

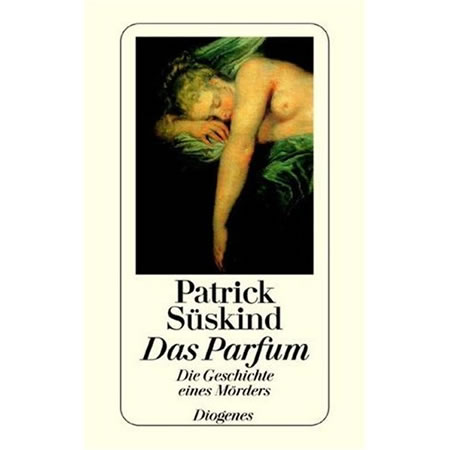

While the chemical description is that indole is an aromatic heterocyclic organic compound, the real telling comes to “a solid at room temperature. Indole can be produced by bacteria as a degradation product of the amino acid tryptophan. It occurs naturally in human feces and has an intense fecal odor. At very low concentrations, however, it has a flowery smell,[1] and is a constituent of many flower scents (such as orange blossoms) and perfumes. It also occurs in coal tar.” Perfumes that savor the layering of deep indoles can be found here, “for women, perfumes, with a strong indole note include Serge Lutens A La Nuit, Sarrasins Intimate, LUSH Gorilla Lust, Diptyque Olene, Jo Malone Orange Blossom, and Chanel No. 5.

And, for examining men’s fragrances which feature indole these include Amouage Homage Attar, YSL M7, Creed GIT, Serge Lutens Chergui, Chanel Egoiste, Bond No. 9 New Haarlem, Amouage Epic Man, MDCI Invasion Barbare, Amouge Jubilation XXV, and YSL Kouros.

The nature of the dark arts of perfume would be about, to contrast, the balancing of light — the brighter and perhaps more floral wafts, with solidifying and smoothing deeper, darker nuit fragrances that cull to other memories. Perfume will always be about memory — the experience of living invariably is laden with millions of scent recollections. And perhaps only the observant will know, and acknowledge, what they’re “smelling” at any moment. Most notes — the music of perfumed constructions — are past, they are passed by. Missed in the mist of the moment.

Garbage – the smell of it. Stench, as Süskind notes, leads to the wonderment of the why of smell.

Follow this bridge to the etymons of perfume, noted here, stench:

From the Old English — stenc “a smell” (either pleasant or unpleasant), and moving back further in time from the mother of Germanic tongues, the Proto Germanic — *stankwiz ( as well as the Old Saxon — stanc, Old High German stanch, and the German stank). It is related to stincan “emit a smell” (see stink) as similarly drench is to drink. The notion of “evil smell” predominated from c.1200. But considering the idea of scent and garbage, the waft of malodor see this:

smell (v.)

From the late 12th century, “to emit or perceive an odor,” also (n.) “odor, aroma, stench;” not found in Old English, perhaps cognate with Middle Dutch — smolen, and the Low German — smelen “to smolder” (see smolder). The Oxford English Dictionary notes “no doubt of Old English origin, but not recorded, and not represented in any of the cognate languages.” Ousted O.E. stenc (see stench) in most senses. And finally, the sink of scenting and perception, to smell a rat, which is to “be suspicious” is from 1540s.

Traveling the world, anywhere, anytime, I find myself scenting. Walking a heated street in NYC, or the souk of Marrakhesh, Morocco (leathers, metals, woods) — a street bazaar in India (cumin, saffron, aging fruits,) or a street market in Cambodia (fish, meats, cut vegetables,) a back alleyway in Tokyo (sake), the Pike Place Market, Seattle (sea mist, shaved ice, cut flowers). But these notes always sink to the darker side of the fragranced equation. Things turned in the tide of freshness reveal new underlying characters — they change for the darker deep; they begin the transformation of rot.

Christopher Brosius — the originator of Kiehl’s Demeter collection — and now the chief imaginator of CB | I Hate Perfume says that Americans like fragrances that are “clean, clean, clean.” Too clean, to his take — and most of his creations are notched with other darker fragrance touches. His illustrations are mixes of roots, flowers, dirt, grass, paint, concrete, tar and the other more obvious touchpoints of perfumery.

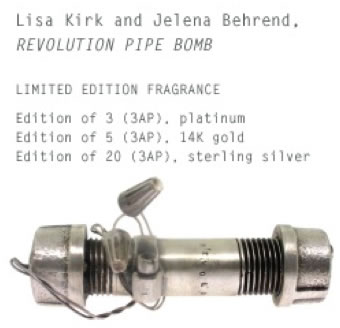

There are other notes — other travails, darker journeys, in the trail of humanity. Some celebrate that definition, some quiet the impression — and still others boost it like a explosive, coupled in the frame of art. Lisa Kirk and Jelena Behrend offer a fragrance bomb in varying artful registries. Literally: Revolution Pipe Bomb.

Her site calls for an abstraction of perfumed layering — something that is hitherto unknown — dangerous, destructive, off-putting, but captivating nonetheless. She notes that the conception comes as “the end result of several years of research and related works by Kirk that address the marketing of transgressive practices, Revolution Pipe Bomb is a luxury fragrance, produced in collaboration with Symrise Perfumers. Smells never before used, with no precise name, only abstract ideas.” She continues that her finalized strategy was investigative, “research gathered from interviews with anonymous journalists, activists, and political radicals, Kirk developed the Revolution fragrance based on their memories of the smell of revolution. The final solution contains the odor of smoke, gasoline, tear gas, burnt rubber, and decaying flesh.”

And Americans are afraid of the perfumes of dissolution, destruction, decay — garbage. The idea of concealing the perfume of trash is a past time. Some suggest that P&G was the founder of odor elimination, “the industry credit Febreze with creating a wider market for odor- eliminating products. The launch of the Procter & Gamble Co. spray in the late 1990s slowly “drove consumer awareness and consumer acceptance,” for the concept that odor-eliminating products can work, says Eric Albee, chief executive of Aromatic Fusion Inc., a Bensalem, Pa.-based company that makes fragrances and plastics.” That links to “holding the garbage” in the right containment (a Glad bag,) concealing anything untoward in the realm of scent — trash smells bad, according to the notes of the Wall Street Journal reference:

60%

of people believe if they can smell the trash, the house is not clean, according to a 2008 Glad survey.

1 in 5

consumers claimed that their bag came looseand fell into the trash can, according to Glad.

2 to 4

The amount of times people change trash bags per week, according to bag and can manufacturers.

15.4%

of U.S. households bought a scented waste bag in 2010, according to a Nielsen Homescan Panel survey for Hefty.

65%

of Americans have noticed garbage odor in someone else’s home, but more than half didn’t mention it, according to a 2010 survey from Glad.

6%

of people love taking out the trash, according to a 2008 Glad survey.

Good to contemplate the testing of garbagology and trash management. I’m sure there are even more compelling evidences.

When I come into any space, I smell it. That tells me everything, about what has happened there before. Even the trash that has been left — perhaps dominant, as a distinction.

Scent, place, will be intimately synced to what’s passed, the past. That might be minutes. Days. Months. And the years of what has fragranced before.

Tim | Decatur Island

–––

BIG STRATEGY + MASSIVE ENTERTAINMENT=

ENCHANTMENT: BRAND STORYTELLING

http://bit.ly/fJaECg