“I did. I do what I do because I want to do it, because I want to explore, go looking for things.”

~Luc Besson

A directorial style, branded, explorations of cinéma du look.

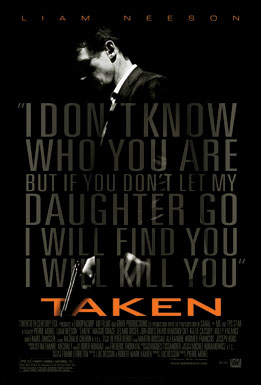

I met Luc Besson in Paris, a number of years back, when I was working in Paris. And it was in his restaurant, that he’s created with Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Market. I saw him, I recognized him, and I went up to him. I asked him about the story — in film. He said, then — “What’s the story? And it’s all about the story, but more importantly, what does it look like — it’s one thing to tell a story, and really, anyone can do that — but in telling a story, what about the importance of its look? If there is no look, it’s nothing.” It’s not just a story, but it has to look incroyable. Good questions to ask. And surely in alignment with my ever-present meander — if there is a story, who cares to listen to it — and for that presence, seeing it — who cares what it looks like? To explore that, and just this past week in NYC, I saw his film with Liam Neeson, TAKEN.

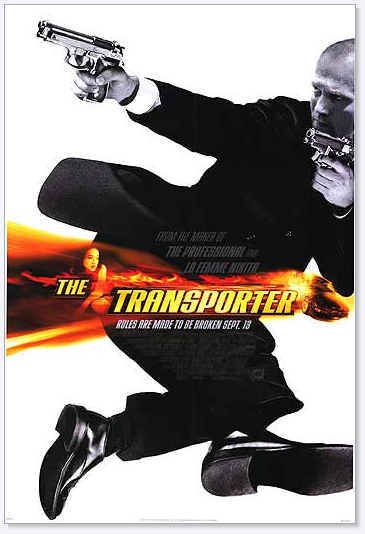

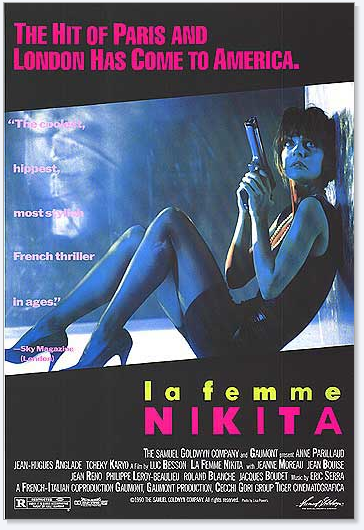

This film has been described as representing a genre of entertainment that some might define as being stylistically relevant to Besson’s oeuvre, an international hit maker that espouses a certain kind of visual realism, cinéma du look, and a stylistic framing that might be defined as nearly anti-French — to the legacy of that cinematic industry. That is, instead of the darker, black and white, philosophically absorbed renderings of earlier, pre-80s offering from French directors, his thinking brought something new to filmic imagery and storytelling.

And, in a word, TAKEN still holds to that visioning — after a long string of explorations of this styling genre. According to Manohla Dargis, a writer for the NYTimes, “Mr. Besson, who made his reputation in the 1980s directing entertainments like SUBWAY, was a central figure in a French movement called the cinéma du look, work that emphasized slick visuals, avoided ideology and politics, and paid closer heed to spectacle than to narrative. Although Mr. Besson now casts a wider net as a producer — he went somewhat upscale with the recent art house thriller TELL NO ONE — the genre movies that carry his brand tend to be predictably homogeneous, with more or less the same look (glossy), sound (blaring) and pace (relentless). That more or less describes TAKEN, as well as innumerable action flicks from Hollywood to Hong Kong, of course, though this digitally dreary-looking movie also gleefully trades on the specter of American vigilante justice.

But, it’s working: “There’s nothing like a recession to make Americans go to the movies. U.S. box-office receipts in February were a record $770 million. But the top-grossing movie of the month wasn’t American—it was French. TAKEN, an action thriller starring Liam Neeson, is the first U.S. megahit for French film mogul Luc Besson. And Besson is working hard to make sure it won’t be the last. Besson, 49, best known until now as the director of such films as THE BIG BLUE and THE FIFTH ELEMENT in the 1980s and 1990s, has worked mainly as a producer for the past decade. His Paris-based Europacorp (ECP.PA) studio posted $186 million in revenues last year, making it second only to Germany’s Constantin Film (CFAG.DE) as Europe’s largest independent studio”, according to Business Week’s Carol Matlack. “Nearly one-third of Europacorp revenues come from box-office and DVD sales outside France—no surprise, since many of Besson’s productions, including TAKEN, are in English. “We have a diplomatic passport; we’re equally at ease in France, Japan, Germany, and the U.S.,” Besson says in an interview at his headquarters in an elegant mansion a few blocks from the Champs-Elysées.”

(photo: Stephanie Branchu/20th Century Fox)

While her reference is dour, I was as caught up in the visuals, the action, and — frankly, the story — being a father to two gorgeous daughters.

I’d organize these in the sequence of his initial efforts in the grouping of films, and his expanded empire, that follow. But there’s a great deal to explore in the history of his developments. He moves, from concept to concept, evolving — and even papers and essays have been focused on (t)his trans-navigation of intention and boundary:

“Besson’s films possess transvergent qualities (they are ambiguous; they deal with technology as culture; they feature spy-like aliens-from-within that cross literal and metaphorical borders and boundaries), the article then looks at how Besson is himself a transvergent figure. Besson is an ambiguous, spy-like film-maker who crosses borders, and whose ‘Frenchness’ or otherwise is continually scrutinized.” William Brown | University of Oxford

His story, to reference? Luc Besson is a little younger than me — he was born this month, the 18th, 1959, in Paris, France. And like me, interestingly enough, his early interest was marine biology. And dolphins, no less. According to the internet movie database, “Luc Besson spent the first years of his life following his parents, scuba diving instructors, around the world (and, I suppose, there’s another alignment, since they were teaching at Club Med, recalling another note about Trigano). His early life was entirely aquatic. He showed amazing creativity as a youth, writing early drafts of GRAND BLEU, LE (1988) and THE FIFTH ELEMENT (1997), as an adolescent bored in school. He planned on becoming a marine biologist specializing in dolphins until a diving accident at age 17 which rendered him unable to dive any longer. He moved back to Paris, where he was born, and only at age 18 did he first have an urban life or television. He realized that film was a medium which he could combine all his interests in various arts together, so he began taking odd jobs on various films. He moved to America for three years, then returned to France and formed Les Films de Loups – his own production company, which later changed its name to Les Films de Dauphins. He is now able to dive again.”

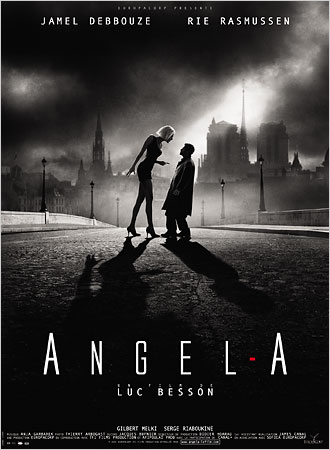

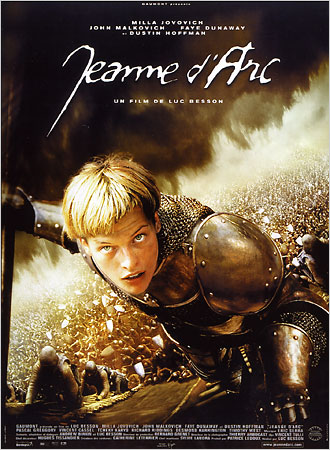

While there are directors that seem to focus, as referenced by Dargis and others, within a narrow vein of exploration, I might offer that Besson’s work ventures beyond that front — into a melange of creative invention. This ranges from his historical work — like the story starring his then girlfriend, Milla Jovovich, THE MESSENGER: THE STORY OF JOAN OF ARCC (Janet Maslin: “Revealing much about her approach to the role, Ms. Jovovich has said of Joan: ”I think if I met her I’d probably just give her a big hug. She’s a little girl who went through a lot.” Beyond the obvious, much of what she goes through here comes from being put through the wringer by Mr. Besson. Working in English, and speaking the universal language of ugly, blood-spurting battle scenes, this sensation-prone French filmmaker delivers jarring, hand-held carnage interspersed with religious visions straight out of music video.”) to ANGEL-A, in 2005 (which was, contrary to my earlier gesture to pre-80s French film coloration, in black and white), “Rie Rasmussen and Jamel Debbouze, the stars who portray Angela, the celestial therapist, and André, her star patient, display enough screwball romantic charm to keep this sugary trifle afloat longer than you’d expect. Beneath its sophisticated Gallic gloss, the movie, which shamelessly recycles IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE and HEAVEN CAN WAIT, suggests an episode of “Touched by an Angel” without the tears” according to Stephen Holden’s critical analysis.

Sony Pictures

Kids, too, of course, figured in his creative investigations. ARTHUR AND THE INVISIBLES is another in the lineage — and in this instance, it might be a recollection to his love of his childhood — and his explorations of these memories, which are, for him, something to be nourished and retained as important contemplations of living.

“What’s so special about all those amazing British children’s writers, those who gave us Alice in Wonderland and Robinson Crusoe and Pooh Bear and Peter Pan and Peter Rabbit and the rest, was that they didn’t set out to seduce. The great children’s writers were authentic, they copied no one, they didn’t set out to make money or to preach ideas. They just transcribed their dreams.”

He, as well, merges his creative imaginations with the new, French horror genre, which casts its line of visual evil out to the very edge of the ghastly and terrific. His film, LES FRONTIER(S), is almost remarkable in that it made it into the market — only as video.

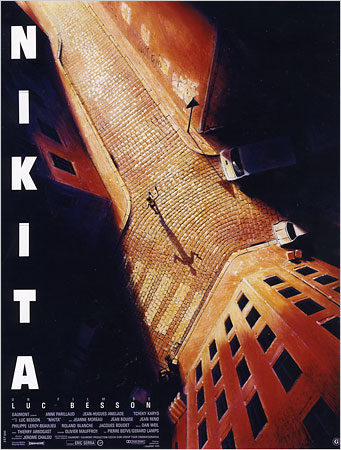

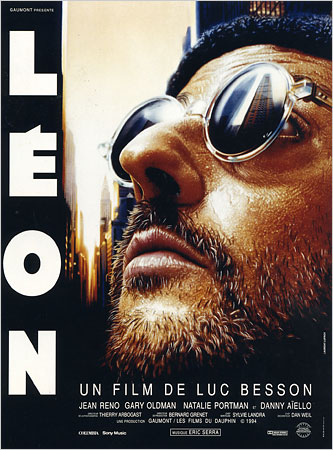

And Besson closely ties the visuals of his stylish storytelling to his approach for merchandising — dramatic, lush, loud-volume, artful presentations:

My favorite(s)?

Story, luxuriously visualized, passionately iterated — throughout a series of creative explorations, over time. That’s what I’m looking for. Continuous manifestation in dream and vision.

Luc Besson lives there.

Still, Luc is not the only one that might be cast in the light of the character of this quick study, the extravagance of the French, branded style….

It wasn’t only him, in the ’80s, that I’d been fascinated by. There are others (though I’ve not met them), like Jean-Jacques Beineix, who similarly took the path of “look” cinema.

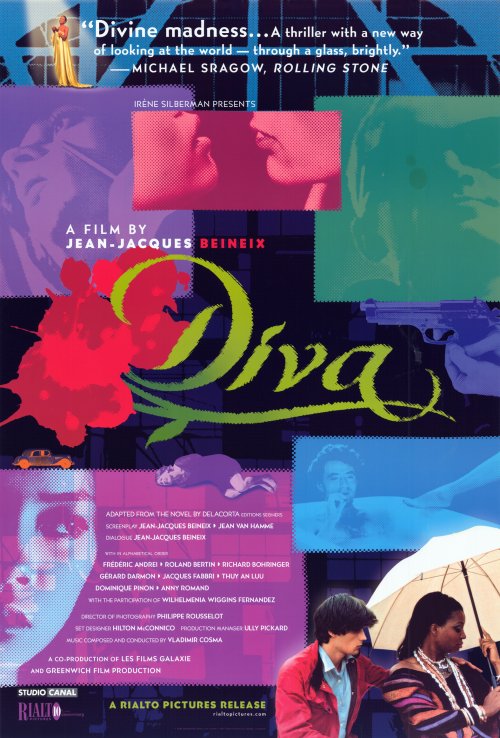

For more on him, I’ve reached to the expertise of Chris Routledge, and his overview in Film Reference, as well as Christophe Gans and David Russell. Jean-Jacques Beineix emerged as a director in his own right with the intelligent thriller, DIVA.

Beineix’s talents also extend to screenwriting and producing, and in the 1980s, along with directors Luc Besson and Leos Carax, he helped establish, if not certifiably define “Cinéma du Look” — its slogan “the image is the message.”

And surely, the opening reviews surely shows that line of critical thinking — “DIVA is an empty though frightfully chic-looking film from France. Though it means to be a romantic suspense-thriller, it has the self-consciously enigmatic manner of a high-fashion photograph, the kind that’s irresistible to amateur artists who draw mustaches on the perfectly symmetrical faces of pencil-thin models in sables,” as intoned by Vincent Canby, in 1982. Personally, for me, being perhaps more of a visualist, perhaps wrap more of a story around the imagery than others. I think that I see into the layers of storytelling in a manner that senses transparency.

Sometimes considered to be the inaugural film of this new style, Beineix’s first solo project is one of the most influential French films of the 1980s. DIVA addresses what have become singularly defined as postmodern themes: images of reflective glass buildings, remote, abandoned and refurbished places, or “palaces” and its plot is framed on the relative value of recorded music and information. The diva of the film’s title is an American opera star who refuses to be recorded but finds that this only increases the value of bootleg recordings of her performances. It is when one of these bootleg tapes is confused with a tape that incriminates a politician that the plot takes off. As Jill Forbes points out, however, the central figure of the drama is not the diva herself, but the mail courier who makes the bootleg recording. The film’s point, argues Forbes, is that the circulation of information is more important than production.

The vibrantly glass style of the “Cinéma du Look” transferred easily to TV advertising, and Beineix became involved in making commercials after the success of DIVA. Like TV commercials, which he has claimed “capture youth,” his films tend to employ intense colours and lighting effects, as well as stylized or strange locations. It has been surmised that most of the 7.5 million Franc budget for DIVA went on sound and vision rather than high-profile actors.

The follow up effort — LA LUNE DANS LE CANIVEAU — is, if anything, still more a triumph of style over substance than DIVA. His second feature was less to story and more to style, but blemished, in the immediacy of the critical reaction (his advertising commercial work) “LA LUNE DANS LE CANIVEAU is far less convincing than the director’s debut, and confirmed, for French critics at least, that Beineix had been polluted as a filmmaker by his contact with the advertising industry.”

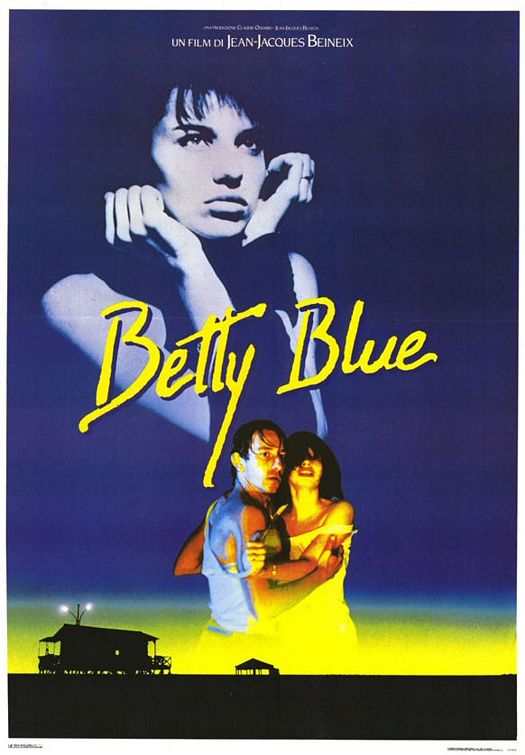

More successful is 37°2 LE MATIN (BETTY BLUE), which tells the story of a doomed love affair between a disturbed young woman, Betty (Beatrice Dalle), and an aspiring writer. Their turbulent relationship makes for a bleak film, but it is attractively directed and photographed and achieved cult status and some notoriety for the explicit sex scene with which it begins. Perhaps as a result of Beineix’s involvement in advertising, 37°2 LE MATIN is structured in short set pieces that are separate episodes in themselves. As if to emphasise this advertising connection, one such scene from 37°2 LE MATIN, where Betty angrily throws her lover’s possessions over the balcony of their house, has been remade in Europe to advertise a small Japanese car.

When I take this analysis, as well, to frame it to Luc Besson, his running success has been far more involved — and evolved — as he’s ranged his exploration much more broadly. Still, it’s about a profound sense of vibrancy in coloration, a sleek production value, and the frequency of wildly inventive set solutions. Sight, and site, are integral elements in exploring the concepts of cinéma du look.

I’m curious about the concept of linking an aesthetic movement — the framing of story in visual — to the notion of directorial style. And I would venture that you’ve got ideas on that, too.

I’d like to hear them.

tsg | nyc

—-

The site:

http://www.luc-besson.com/

The man:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000108/

Market debut:

http://dealbook.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/06/luc-bessons-film-company-makes-its-market-debut/

Videos:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000108/videogallery

References:

Gans, Christophe, “Diva, dix ans aprés. . . ,” in L’Avant Scéne Cinéma, no. 407, 1991.

Russell, David, “Two or Three Things We Know about Beineix,” in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1989/90.

Isabelle Vanderschelden, Luc Besson’s ambition: EuropaCorp as a European major for the 21st century, Studies in European Cinema | Volume: 5 | Issue: 2 | Pps: 91-104

http://www.filmreference.com/Directors-Be-Bu/Beineix-Jean-Jacques.html

Favorite quote:

It’s always the small people who change things. It’s never the politicians or the big guys. I mean, who pulled down the Berlin wall? It was all the people in the streets. The specialists didn’t have a clue the day before.