Exploring the patterning of national crises and the outcomes in humanity — the legacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Barack Obama’s positioning for renewal.

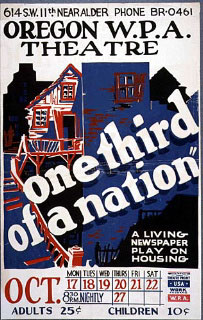

1936 WPA poster

I’m hoping for that — change, as adroitly put in Barack Obama’s campaign programming.

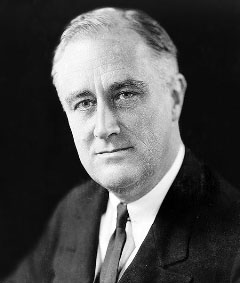

“Don’t forget what I discovered that over ninety percent of all national deficits from 1921 to 1939 were caused by payments for past, present, and future wars.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt

“We are facing the greatest economic challenge of our lifetime, and we’re going to have to act swiftly to resolve it.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt

According to the NYTimes commentator and writer, Joe Nocera, an insightful overview is offered about this last quotation, Franklin Roosevelt’s first fireside chat in 1933 created spontaneous enthusiasm and cooperation. It unified the people that were stretched to the edge of despair. And, in a manner, President Elect Barack Obama has done the same thing. There are, too, visual alignments. Note, for example, this campaign treatment — particularly the typography, that supported Roosevelt’s rise to the White House (and staying there longer than anyone else, ever in the history of the presidency.

And Warren Buffett, in his own historical reference, offers:

“During the Depression, the Dow hit its low, 41, on July 8, 1932. Economic conditions, though, kept deteriorating until Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933. By that time, the market had already advanced 30 percent. Or think back to the early days of World War II, when things were going badly for the United States in Europe and the Pacific. The market hit bottom in April 1942, well before Allied fortunes turned. Again, in the early 1980s, the time to buy stocks was when inflation raged and the economy was in the tank. In short, bad news is an investor’s best friend. It lets you buy a slice of America’s future at a marked-down price.”

Over the long term, Buffett purports, “the stock market news will be good. In the 20th century, the United States endured two world wars and other traumatic and expensive military conflicts; the Depression; a dozen or so recessions and financial panics; oil shocks; a flu epidemic; and the resignation of a disgraced president. Yet the Dow rose from 66 to 11,497.”

And referencing that sense of history, to the opening Fireside chat of FDR — “So said Barack Obama on Friday in his first postelection news conference, a pretty good sign that the president-elect had been brushing up on his presidential history.

According to Nocera, “Seventy-five years ago, the last time the country was this close to economic abyss, Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered his famous inaugural, the one where he uttered those immortal words, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

As Newsweek columnist, Jonathan Alter, who wrote “The Defining Moment,” a book about Roosevelt’s first election and early presidency, “that great line was buried in most news stories about the speech. Stories focused instead on another phrase F.D.R. used: “action, and action now.”

In 1933, after three years of profoundly muddled incompetence from the administration of Herbert Hoover, that is what Americans most yearned to hear. Like Change. And this past week, Mr. Obama vowed, within the first five minutes of his remarks, to “act swiftly,” he offered as well, the aligned message that everyone was hoping to hear. In his first presented news conference, he spelled out his short-term economic agenda: a stimulus package to prod the economy, hoping this will pass before he even takes office — extended unemployment benefits and other relief measures for people who are struggling; stemming the surging tide of foreclosures. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has been pressing the Bush administration for weeks to sign off on a plan it devised ages ago. And in other commitments, Mr. Obama made it plain that he would not let the American auto industry die; he wants to support economic assistance to state and local governments that have been assailed by the financial crisis.

Obama also defined an analysis program of the bailout “to ensure that the government’s efforts are achieving their central goal of stabilizing financial markets while protecting taxpayers, helping homeowners and not unduly rewarding the management of financial firms that are receiving government assistance.” Obama’s taking his time in measured cadence. And that waiting will cause, in the near term, rising unemployment, stumbling business activity and terrifying headlines. We’ll simply have to charge onwards. Perhaps if there’s a way to maintain some of the optimistic composure and enthusiasm of Obama’s visioned future — in how he represented himself so powerfully — and how that might be shown visually, in continuing that campaign, we’d surge on more resolutely.

Buffett, the calming counselor, and patient patriot proffers: “So … I’ve been buying American stocks. This is my personal account I’m talking about, in which I previously owned nothing but United States government bonds. (This description leaves aside my Berkshire Hathaway holdings, which are all committed to philanthropy.) If prices keep looking attractive, my non-Berkshire net worth will soon be 100 percent in United States equities.”

Why?

He continues: “A simple rule dictates my buying: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful. And most certainly, fear is now widespread, gripping even seasoned investors. To be sure, investors are right to be wary of highly leveraged entities or businesses in weak competitive positions. But fears regarding the long-term prosperity of the nation’s many sound companies make no sense. These businesses will indeed suffer earnings hiccups, as they always have. But most major companies will be setting new profit records 5, 10 and 20 years from now.”

Nocera’s overview suggests he was let down by Obama’s opening vagueness; but of the initial stance, sure and careful footing is best: “Mr. Obama projected a kind of crisp competence — an executive figuring out a practical plan of attack — rather than presenting himself as he had so often during the campaign, as an inspirational leader.” He’s moving past that, to action — as he’s intoned in his first press conference. “And in my momentary letdown, I realized that I had been hoping to see, even this early, something that many other Americans are also wishing for… I was hoping to see the new F.D.R.”

Those with a sense of history will likely find that projection another dream that we could all use right about now.

Are the times now the same as in the presidential campaign of 1932? No, far worse. When Franklin Roosevelt was sworn in as president, back then, unemployment stood at a staggering 26 percent. Our present condition, by contrast, the government analyses reported that the October unemployment rate was 6.5 percent — seriously difficult, but nothing compared to the past. Last year’s stock market has declined 35 percent; in 1933 the Dow Jones average was down 75 percent from its earlier 1929 peak. Far more bank failures, substantially devastating foreclosures and spectacular collapse among farmers. There were much greater hardships during the Great Depression than there are now.

Then, Roosevelt’s strategy was very much about reaching into the hearts of Americans — and this, in the most powerful way, was how Obama captivated the rising tide of discontents in the US populace.

As Nocera and Buffett point out — similarities abound. First — the response to the crisis by the outgoing presidents, Herbert Hoover and George W. Bush: Hoover’s primary solution for combating the crisis was to make large government loans to the banks, the railroads, the insurance companies and other industrial giants. Nocera notes, “when that didn’t work, he was lost. As people began standing in line to pull their savings out of banks — creating devastating bank runs — government officials pleaded with Hoover to declare a bank holiday. But he couldn’t pull the trigger.”

Hoover then established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, making loans to tax-starved state governments. The historian Michael E. Parrish notes in his classic work, “Anxious Decades,” “state governments had to take a virtual pauper’s oath” to get any compensation support. Hoover would only approve public works projects that would pay for themselves — severely limiting the kinds of projects that could get government financing. For his slanted ideological reasons, he opposed direct federal aid to the unemployed — “pathetically inadequate” as Mr. Parrish describes the Hoover administration response to the crisis.

Sound familiar? The Bush administration has also attacked the crisis almost entirely by focusing on the banking system. It has made huge loans and taken equity stakes — but for reasons largely based on “slanted” ideology, it has refused to demand anything in return. The other intriguing alignment to the Hoover debacle, and our present challenges, is that the Bush administration has been every bit as reluctant to help individual homeowners as the Hoover administration ever was. The closing Bush legacy is an unwillingness to help ordinary citizens; it is staggeringly profound, to the conclusions of the last 8 years legacy of leadership — so callous — and as Nocera concludes “the crisis won’t end until housing prices stabilize and foreclosures decline.”

We do our part — the emergence of Roosevelt’s strategy for reconnection and action.

Albert Bender (WPA)

It will be fascinating to study the progressing movements of Obama, and how, perhaps, he will reengage community in that “action”.

But there might be similar alignments, to the positive, in transition —

mirroring the past — that of unifying the people to a grouping of goals that are for the people — and truly of the people. Immediately after his election, Roosevelt began to formulate policies to bring about relief from the economic hardships the American people were experiencing.

We can take it! (WPA positioning)

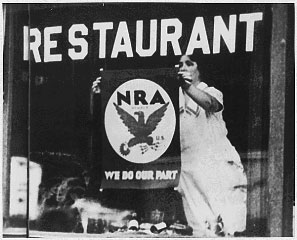

These programs became known as the New Deal, a reference taken from a campaign speech in which he promised a “new deal for the American people.” The New Deal focused on three general goals: relief for the needy, economic recovery, and financial reform. During the One Hundred Days, Congress enacted 15 major pieces of legislation establishing New Deal agencies and programs. Among other programs, it created the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The NRA was perhaps one of the most sweeping and controversial of the early New Deal programs. Its purposes were twofold: first, to stabilize business with codes of “fair” competitive practice and, second, to generate more purchasing power by providing jobs, defining labor standards, and raising wages. By mid-July 1933 he launched a crusade to whip up popular support for the NRA and its symbol of compliance, the “Blue Eagle,” with the motto “We do our part.”

The eagle, which had been modeled on an Indian thunderbird, was displayed in windows and stamped on products to show a business’s compliance. There was even a parade down New York’s Fifth Avenue with over a quarter of a million marchers in September to show support for the NRA and the “Blue Eagle.”

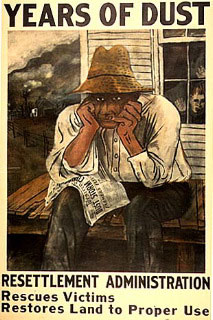

Ben Shahn (WPA)

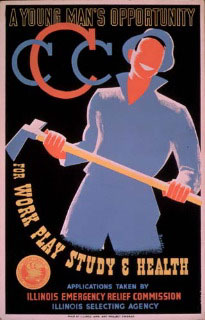

But in addition, there was art as part of the fulfillment (strikingly reminiscent of Obama’s campaign visual stylings — and as I’ve alluded in the opening gesture of these notations). The Works Progress Administration (WPA) focused on a return to action for millions of people — to create jobs through building highways, bridges, parks, schools, public works of art and other projects intended to have long-range value.

Raymond Jonson (WPA)

While developing programs to help America emerge from the Great Depression, Roosevelt also needed to calm the fears and restore the confidence of Americans and to gain their support for the programs of the New Deal, including the NRA and the WPA. The conceptions offered a plan of action — to work, to contribute as a nation in doing our part to advance against calamity.

Alden Krider (WPA) 1936

One of the ways FDR chose to accomplish this was through the radio, the most direct means of access to the American people. And like Obama’s strategies in community development and social networks, he focused on using tools to maximize the reach to as many people as possible, all at the same time: radio and visual messaging for broad distributions.

Ben Shahn (WPA) 1937

During the 1930s almost every home had a radio, and families typically spent several hours a day gathered together, listening to their favorite programs. Roosevelt called his radio talks about issues of public concern “Fireside Chats.” Informal and relaxed, the talks made Americans feel as if President Roosevelt was talking directly to them. It was a one-sided yet powerful social networking “technology” — more like a podcast, but something that drew the listener in reflectively; and Roosevelt continued to use fireside chats throughout his presidency to address the fears and concerns of the American people as well as to inform them of the positions and actions taken by the U.S. government.

(WPA) 1938

Productivity, for all, was the motivating expression.

David Stone Martin (WPA) 1940

During the depths of the Great Depression of the 1930s and into the early years of World War II, the Federal government supported the arts in unprecedented ways. For 11 years, between 1933 and 1943, federal tax dollars employed artists, musicians, actors, writers, photographers, and dancers. Never before or since has our government so extensively sponsored the arts.

Ben Shahn (WPA) 1937

Given the lining up of the challenges that we are facing today, and the difficulties of the past, it would be captivating to see art — as exemplified in the character of Obama’s campaign reaches — gather up again to reignite the spirit of American’s grandeur in its people.

TSG | Seattle