Everyone has a powerful connection to their mothers.

My mother, Lila Lee Shaw Girvin died this past week. And it called into contemplation all of the things that one thinks about in death—of anyone near. You’re thinking,

“they were here, now they’re gone. Forever.”

It’s something to contemplate that she was my matrix, my inspiratrix, maker for 72 years, almost as long as she was with my Dad, George Girvin—married for 73 years, which is that long.

But I realized, of course, in the simple math of things—that’s obvious. She was my mom, she made me, so my relationship with her is simply that long.

But, as I offered to a client team that gifted a bouquet of beautiful flowers as solace, I really wouldn’t be working with them, if it wasn’t for her.

Because it was my mother that instilled the creative instinct, a constant hungering after exploration, looking into the deeper side of things, investigating and exploring the other side. Not that—which is on the surface—the fundamentally obvious, but rather what’s underneath.

She was also my protectrix—she was the one that found the group of Jesuits that guided me through the onerous process of seeking a Conscientious Objector status as my Vietnam War lottery number came up as a single digit reckoning, an assured draft into the military.

This all began as a child, for me, this creative journey.

Early in my life, I’d travel with her to the painting school in downtown Spokane, sit and wait—amidst the fragrances of oil and turpentine—and draw on the floor. I’d sit and listen to the painters discussing their paintings—and this was interesting, looking at the work, listening-in on their interpretations.

This experience taught the link between thinking and making, abstraction and imagination,

the dreams of interpretation.

When I was in Kindergarten, I have a specific memory of being instructed in “how to fold and cut paper to make a Christmas tree.” Of course, I didn’t do what I was asked. And I was scolded by the class teacher in a way that I remember as distinctly tear-inducing. Coming home, Mom said, “you made the tree in your own way, and that’s just fine—it’s beautiful.” Anyone involved with the arts knows that the artist’s journey is never easy—being one artistically inclined presupposes a highly interiorized world—you have to be—likely, since you’ll have to survive on your own.

Which I have, for the last 50 years.

In elementary school, this “difficult child” scenario continued. I simply didn’t fit in until there was a sequence of flowerings, or discoveries, that opened my heart to certain yearnings. One—books and reading—and while I struggled with “reading,” I did well if the subject was interesting.

This came down to art history and the Skira art book collection at home—this was Mom’s gathering. Then history, other cultures, other lands. Then science, nature. And while my father was pushing me towards the notion of a scientific career, Mom was pushing art—more classes, opera, art museums, musical instruments, and “band.” Dad talked of math and medical school, I kept at the art. And our neighborhood was full of architects, so understanding artistically thoughtful placemaking came from this circle. And many of Mom’s friends were designers—interiors and decorators—and there were craftsmen in the midst—people like Harold Balasz,

who I also met as a child—out at his handcrafted studios, the Mead Art Works. And with him—decades more, and with Mom, I learned of the orchestration of the hand, mind, materials and imagination to make things that could be built, cut in timber, dusted in porcelain enamel, drafted on handmade paper stocks, cut silkscreens, stencils, welded metals, carved brickwork and masonry.

Harold said, “Tim and art? Cut his hands off.”

But Mom persevered—and I kept going.

She mentioned, latter high school—“Tim, there’s a man coming to Joel E. Ferris High School, for an afternoon class that we should meet…you should go and see him;

his name is Lloyd Reynolds.”

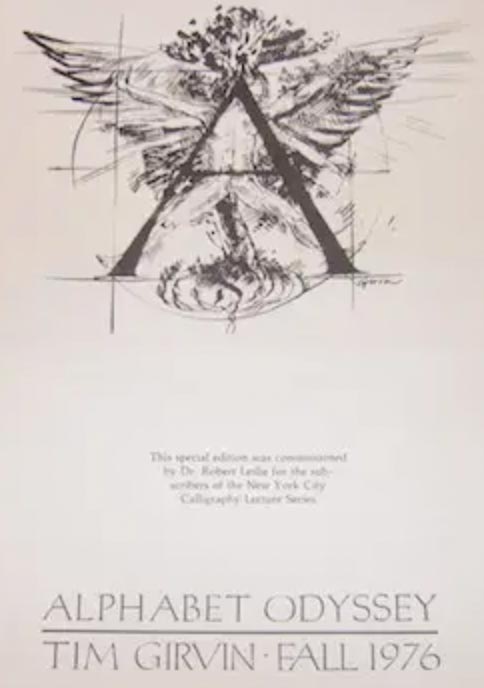

And that was the beginning of typographical aesthetics, paleography, fine printing, book design, calligraphy, shopfronts and signage, interiors, motorcycle and vehicle graphics and pin-striping, tattoos, silkscreening and print work.

While everyone knows something of my time at Reed College with Lloyd, and my UK, European alphabet odyssey [Frutiger, Zapf, Neugebauer, Carter, Zhukov, Pronenko and Toots] and later my encounters with Steve Jobs—which were ignited in conversations with him about Lloyd and his influences—on both of us.

Mom encouraged—literally, en courage—was part of the perpetuity of her support—“get out there and do it.”

In the last couple of years, the wide swath of creativity that she shared with the world was shown in a 60 year retrospective of her oil paintings—massive washes of color—shown in this Perry Street studio setting photographed by Young Kwak of the Spokesman Review in Spokane.

What does this mean for us and branding?

For me, there is a long-running, decades long study of the Great Mother, the mystical creatrix, the mysterious Ma, the Maker of everything in our world.

As we all know, archetypes find their way into the branding construct,

soul brands, as the emotional underpinnings of desire and the deep dream metaphors of our inner worlds, as patterning from millennia of human consciousness.

And making is at the heart of brand work, since brands are made for people, by people and they are, literally “made.”

Closing, there’s a linguistic hint to the power of the Mother.

Our first word could be “ma,” since mother made us.

And a host to other ma-words.

Ma. Mama. Mammal. Matrix. Matter. Material. Metropolis.

Amateur. Alma Mater. Marigold. Matrimony. Argiopē. Nun. Cassiope.

Really?

And she inspires our movement forward

in the world that we live in, and the work that we do.

I am honored to be the son of Lila Lee Shaw Girvin.

She set the genetic code of who I am.

What I do.

And how, now, I go forward.

Tim Girvin