The cartography of brandfire: the story of highest road, the path of the middle story told, and the cumulus of the multiple tales—the grounding ley-line of the promise—the mission of the everyday.

Part: VI

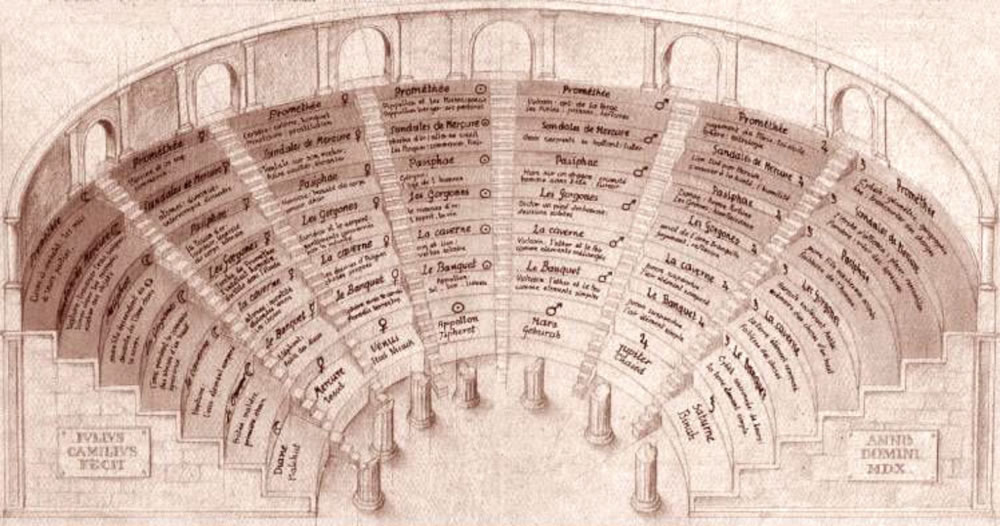

I’d offer a theory of the narrative cloud—the stories that surround the misted power of an enterprise speaking to a more soulful, deeper purpose. Like the labyrinthine mind museum of The Palace of Memory—a listener journeys to what they can hear, a story they can grasp, a telling he or she can recall.

What is recalled could be carried forward, in the etymology of “relating” and “relationship,” the story is personally held as a narrative, that is then shared with others—“this is my story.”

In the architecture of the mind,

of memory and recalling the layerings of experience —

the ancient concept of

the Palace metaphor — reorganizing the mind as a place.

Another layer, the foundational proposition of value and relevance; the clustering of a cloudmind—stories of community that link back to a central storytelling; and finally the grounding telling that lays the concrete of history, timelines and sequence.

People are like that as well.

One story type is exultant: it reaches to the height of visioning, while another—a more operational telling—says “this is why I’m doing what I’m doing—my personal value and contribution.” In corporate parlance, that would be—the promise of the employee, the mission of the brand; and the highest visioning of the dream of the future.

Those are the stories that could be told—transferred as values to others.

Another might align to the spirit of community—stories

that are shared inwardly and outwardly among others.

And lastly, the sequence of living—the procession of how this life is lived.

Finding a way: brands (human enterprises) as points of wonder, mystery and imagination

Earlier in my life, I’d connected with a teacher — a scholarly “pillar” of Sufi mysticism. This person is what some students have called qutub, (literally, Arabic for pillar [hence Qutub Minar is the pillar, or axis minaret]). This person was a man based in London, he was called Sayed Idries Shah el Hashimi.

While Shah, as a scholar, might be less than unquestioned, for my early exposure, during the 70s, I found the world of his examinations to be fascinating—the key work, for me, exploring the story of the Sufi way came from his study, The Sufis. Pir Vilayat Khan, and other live learning experiences for me—teachers—deepened that presentment. Sit, listen, ask, learn. Story, on story, in allegory, behind metaphor—told, and listened to.

But my particular fascination was the realm of storytelling in spiritual traditions. The examination of the story in a story, the teaching in a teaching, was a kind of concatenation that I was interested in: there is one obvious story on the surface, another just beneath, and perhaps layers of others, descending in the more profound meanings of the tellings and the practice. The deeper you go, the more there is to examine.

That idea of the story on story might be how it’s actually told—there is, for example, a kind of storytelling in the middle eastern tradition that ties to the notion of the wise fool. Nasruddin tells stories that offer a kind of self -deprecating, know-it-all, kind of legacy, but in fact have deeper principles.

The moon in the well.

Nasruddin was looking at the image of the moon in a well. He thought it was a recompense to take out the moon from the well. Therefore, he threw a rope inside the well and swung it a few times. Incidentally, the tip of the rope got caught to a big stone. He tried to take the rope out. Hence he pulled it with a lot of force. The rope tore off and he fell on his back to the ground. When he looked at the sky, he saw the moon and said, “Doesn’t matter. My efforts were not wasted. Though I faced a lot of difficulties, I finally succeeded to rescue the moon.”

That tradition of the simple story, that has a deeper story, and finally the legacy of greater depth, in a manner, relates to the proposition of how many stories work. People will understand the story at the level to which is relevant to their understanding. A child will comprehend a classic story with amusement, but only later in life perceive the layers of that telling. These narrative dimensions are mythic, archetypal, even psychical in the way in which they can reach deeper into perceptions.

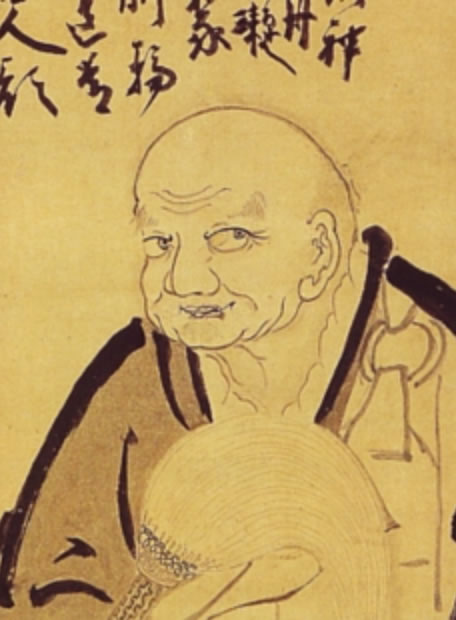

The idea of the unexpected wisdom of the fool — the madman telling a allegory that lends new insight surely isn’t confined to the middle east and the Master Nasruddin alone. Others beckon — Han-Shan, or Kanzan, the proverbial madman of Cold Mountain is a legendary preacher of the unexpected. Tibet’s Tompa, legendary rascal; the puzzlements of Hakuin Ekaku,

the revitalizer of Rinzai Zen.

A story from Hakuin [1685-1768]:

Is That So?

The Zen master Hakuin was praised by his neighbors as one living a pure life.

A beautiful Japanese girl whose parents owned a food store lived near him. Suddenly, without any warning, her parents discovered she was with child.

This made her parents very angry. She would not confess who the man was, but after much harassment at last named Hakuin.

In great anger the parents went to the master. “Is that so?” was all he would say.

After the child was born it was brought to Hakuin. By this time he had lost his reputation, which did not trouble him, but he took very good care of the child. He obtained milk from his neighbors and everything else the little one needed.

A year later the girl-mother could stand it no longer. She told her parents the truth – that the real father of the child was a young man who worked in the fishmarket.

The mother and father of the girl at once went to Hakuin to ask his forgiveness, to apologize at length, and to get the child back again.

Hakuin was willing. In yielding the child, all he said was: “Is that so?”

So, there’s a simple story there, then another that might be called emotionally enthralling, but still another that layers a legacy of a whole way of being—a response to circumstance.

So, is that so?

The way of wonderment —

any human, enthralled in narrative,

has a story to tell; and to listen to — in response.

As anyone might grasp, there is a humanity to the proposition of how a brand / human enterprise might choose to tell stories — how they engage connections in inward and outward rippling of community. To the passion of brands, the committed enterprises of focused community and engagement, the real enchantment happens in the layers of story and narrative connection.

Everybody thinks about their life, their year, their month, their day, as a sequencing of stories. The narrative mind, even in interactive or digital contexts—linked to storytelling—might be more closely aligned to how people think, organize, recall and retell experiences. Surely, even Facebook (examine, for example, David Fincher’s interpretation of the Social Network, unspooling that legacy as opposed to the cool strategic spin of Facebook’s “mission,” or renewed commitments on the corporate site could be considered as a vast array of micro stories / parables about individual experience, just like Twitter might be examined as haiku: storied abbreviations.

The thread of the story relates to plotting structure, characters, evolutions, concatenations in experience and finally the sense of conclusion—every story has to end; so another begins, at the ending, there’s beginning. This ending might be symbolized in both the telling—and silence; and that conclusion and passing it on, and the recollection—literally, “to collect again.” But in the words of a friend, “wouldn’t the beginning of the story be the close of another, and wouldn’t the end of a story be the beginning of yet another threading of experience?” What goes round, comes around.

Thinking about the modeling of brand storytelling — or literally any layering of story expression strategies — the idea of impression and recollection is a powerful staggering of sequences. In my early studies of mysticism, (the notion of what “lies beneath” conventional spirituality) that legacy of looking within recalls, as well, the work of friend Ira Friedlander.

He’d suggested: “Tim, you should be designing the covers for the Omega Institute, they’re doing really interesting things—things that you can empathize with…” Omega is a spiritual colony — a teaching community — for exploring that sensation of living. I did that for a decade. But he left that behind, and began disinheriting projects from his art direction, photography and editorial design– he was heading out to another world. His unforgettable photographic studies of the dervishes of Konya, Turkey and other loci of whirling dance trance, came in his book: The Dervishes.

Then he vanished.

Ira returned as Shems, and a half decade back offered “When You Hear Hoofbeats, Think of a Zebra.” Blogger Leo Africanus notes, “Shems Friedlander, designer, pedagogue, academic, poet, filmmaker, and photographer has produced a thought-provoking volume…extensive travels combined with a profound understanding of the spiritual dimension of Islam render him a most able guide towards the elusive domain of self-knowledge. Friedlander’s objective is to encourage the reader to see things in a different manner – akin to lateral thinking, but exercising the heart and not the mind. To achieve this, Friedlander punctuates his readable text with stories. Daniel Goleman, one of the key proponents of EQ (emotional quotient), says of stories, they ‘have a unique power, an ability to make their points without marshalling the mental resistance that more sharply reasoned rational appeals often raise. Knowledge is best transmitted through rational means, speaking directly to the mind. But wisdom strikes to the heart when it is carried in a tale.”

That notion of storytelling power can be added in a referenced paper (Trish Groves) published in the British Medical Journal, “The power of stories over statistics.” We’ve gestured to the notion that the facts, alone, do not register (nor boggle) the mind, the imagination or the power of impression. That strategic intention—framing stories over factoids suggest two analyses: “a biologically hardwired predilection of the brain for stories (compared to other forms of input) and the role of the storyteller.” To impression—how many times have you listened to a presentation and realized in the end, that you could hardly recall any truly salient gatherings? And inversely, other times—through quirkiness, energy of presentation or the gift of narration — the relevance and resonance of personal context—takeaways can be recalled vividly. Emotionality equation theorist Goleman sees the methodology as “the antidote to what has been called “psychosclerosis”, hardening of the attitudes.”

“I’m talking to you, telling you a story”—how might these tellings link to digital emotionality?

These references expand, with proclamations like “YouTube as the New Campfire: Creative Storytelling in the Digital Age, in a Microsoft webcasting, a positioning of that arrival, “the beginning of time, humans have connected through stories and in the past five years, YouTube has emerged as one of the most engaging and powerful storytelling platforms in existence. From the entertaining (Double Rainbow, JK Wedding Dance) to the political (Neda’s story) to the inspiring (the Fully Sick Rapper), the stories that have been told on YouTube are part of our cultural narrative. YouTube is the modern day campfire, allowing people and brands a platform for creative self-expression and social connectivity through video story-telling.” This examination isn’t surprising, nor inventively insightful, it’s more to the wild success of the infection of that media unto itself. The very title, YouTube aligns the “you” of personal storytelling sequencing and the “tube” of presentation. It’s you, and how will you get it out there? And that idea, the story in translation, the digitally “effected,” and invented visualization—the tube of translated reality.

There is a mark of the powerfully made story—a marking on the mind and memory

—and the capacity of recanting.

But that issue of story—the spiraling of the layer of the starting seedling and how the strata of that story could achieve relevance might be found in application. For example—there is one story to Oracle, that might reside in Michael Ellison’s power and personality, the chromosomal drivers of his mind and outlooks and the nature of their developments and software tools and applications. Each, are tiers. But what of more meaningful and directed experiences—“I know about Ellison; his drive, the racing, even BMW—the ruthless character of their competitive zeal. But really, what does that mean for me? How would I relate to that, carry that forward?” A notation might be selling stories storytelling. Brands could be more defined in the context of relatedness and relevance:

An interview:

Geoffrey James: What challenges does a company like Oracle face in sales situations?

John Burke: Large companies are often very adept at explaining what their products do, but not as adept at explaining how and why their customers use their products. Most companies, Oracle included, have made a great effort to become more customer-focused, and there have been a lot of sales training programs put into place to accomplish that. However, I’ve observed over the years that many of those programs don’t seem to help much, because salespeople don’t often know the real stories behind why their customers bought and how their customers actually use their products.

GJ: And that’s what led you to start working with Mike and Ben?

JB: When I first heard about [the storyselling concept], I was quite skeptical. Not because I didn’t believe in story, but because I thought “more training?” However, because of my respect for Mike Bosworth, I took one of their public workshops along with one of my up-and-coming stars, who was also skeptical. After spending two and a half days at their StorySelling workshop and then using the model with customers, I realized the true affects of a good story..

GJ: What happened then?

JB: I sent all my direct reports to the workshop. The model resonated with a high percentage of those people and some of them have gone on to train their own employees, creating a larger pool within my organization. It’s now began to expand as some other organizations within Oracle see that it’s working for us.

GJ: How has it changed the way that you sell?

JB: I’ve always intuitively been a storyteller but I never really thought through what points I was trying to make – the “why” of the stories that I would tell. Using the framework, I now I start with the point of my story, and then build the story to make that point. For example, if I’m telling a story about what I’ve learned from an experience, I now make it clear to the listeners what I’ve learned. That allows me to more crisply articulate the message I’m trying to get across.

My interest stretches past the conventional conditions of—for example—Seattle theorist / (Worktank+Microsofter) Melinda Partin’s conditional foundation, “The best advertising campaigns take us on an emotional journey–appealing to our wants, needs and desires–while at the same time telling us about a product or service. A brand’s story comes from the company’s own information, and if successful, it is accepted and integrated into the consumer’s story. You must understand how your brand emotionally resonates with customers and then position your message in the right place to tell the right story at just the right time.”

What’s new, there?

Peter Guber, well-“liked” as he is, offers a strategy of alignment to story and winning—“tell a good story, that’s purposely aligned to meaning” (as President Bill Clinton endorsed). It might be pointed out, that the nature of the storytelling of Guber’s own brand offers the parallel universe of practicing what he preaches in a spectacularly integrated clustering of media, site messaging, endorsements, a sliding bar of published overviews, thousands of “likes,” cool people that think he’s cool and a rolling tweeterage of updates. And he’s cool—CEO of Mandalay Entertainment, owner of the Golden State Warriors, professor at UCLA and producing director on “Rain Man,” “Batman,” and “Gorillas in the Mist.”

I’m more interested in the soul of the brand, and the spirit of that telling—the spectacle of the layering of contact—like anything robustly sensed; and that will come to what lies beneath and within, and how consumers can get this alignment in a manner that’s sustaining character at multiple levels—not just corporate storytelling.

The deep, the median ground, the shared cloud of story, the layers of time:

I am a man.

I am a myth.

I am a story.

I am one. I am many.

I am millions.

I am art.

I am science.

I am body.

I am soul.

And I am mind.

I spread this story.

Remember.

There is a story, and another story, a nimbus of spreading stories; and this is my story. Yet it’s another telling, another tier, and another layering of experience. Composited, these clusters make life all the more interesting.

Tim | GIRVIN | SEATTLE WATERFRONT

WEAVING BRANDSTORIES

CROWD MIND | EXPERIENCE DESIGN | MEMORY STRATEGY