SPACING-IN AND THE ART OF NOTHINGNESS.

What if someone asked you to do nothing, all by yourself — just slow down, do nothing? Get quiet?

Could you do that?

Drift?

But space-in, instead of spacing-out?

In the frenzy of our present experience, we all struggle with the ever-unrelenting issue of connectivity — how can we jack in, wifi-up, synchronize, find signals, emulate and import, fascinate and upload?

We need to be connected to everything, all the time.

Yet, some do, some don’t. Some build robust worlds that are entirely carried on the wind-up whines of electronic current, while others do much to avoid electrified creativity and making — going quiet analog, hand-made, unprompted, deSocialized.

There is a phrase in the context of social and hybrid community management known as

always on.

We ask for WiFi codes when we check into hotels, we get into a restaurant and bring in our iphones so we can track emails. We walk down the street and study messaging and imagery on our phones and tablets.

As we approach a site of rare and exquisite beauty, we bring out our “technology” to document it, shoot it, send a picture to friends and post our content on Facebook, Swarm and Instagram.

It’s not something to imply guilt, it’s merely the way that many of us experience the world.

Me, too.

We’re not looking, we’re shooting, documenting the moment.

I do that, as well.

It’s widely known — to each of us — that we operate in a perpetual state of distraction and partial attentiveness. Presuming that attention is always on is probably not the right way to be looking at our momentary encounters. Undocumented moments flee — and hence our fear — “we missed that shot?”

When I was in college, I had a friend that called me “HawkEye.” It was a two-part nomenclature — the furtive and fastening looks of my gaze — perpetually scanning my vicinity, and too — my love of raptors and corvids.

He said that I was “always eye-jumping and looking around” — like a avis looks at things. And the etymology comes from “seeing.” To that, I try to — in the words of one of my marketing people from the 1990s — “never sit in a room, in a meeting, that allows me to see out.”

I will look.

Elsewhere than in the conference room.

When I was in Charlotte, NC., recently, pitching our work and design legacy — GIRVINCRAFT — in a room that was becoming increasingly alienating — I took to studying the windows, the deciduous tree tops and the red-tailed hawk that came drifting by.

I thought —

“he’s looking at me, and I’m looking at him.”

It’s what I do:

I look.

I see

every

little

thing.

If you step away from your phones,

your tablets and technology —

leave it alone —

you can gather-in your attention.

More.

But looking is about what you see.

And how you focus —

and to what degree,

what are you looking at?

In a recollection to another and simpler time,

I go back to

when I was eight years old.

As you might know, the journey to discovering will always be analogous to a string of flowers — moments when your heart blossoms to a new learning —

a new perceptive discovery that took you,

in your journey,

to another tier

of imagination.

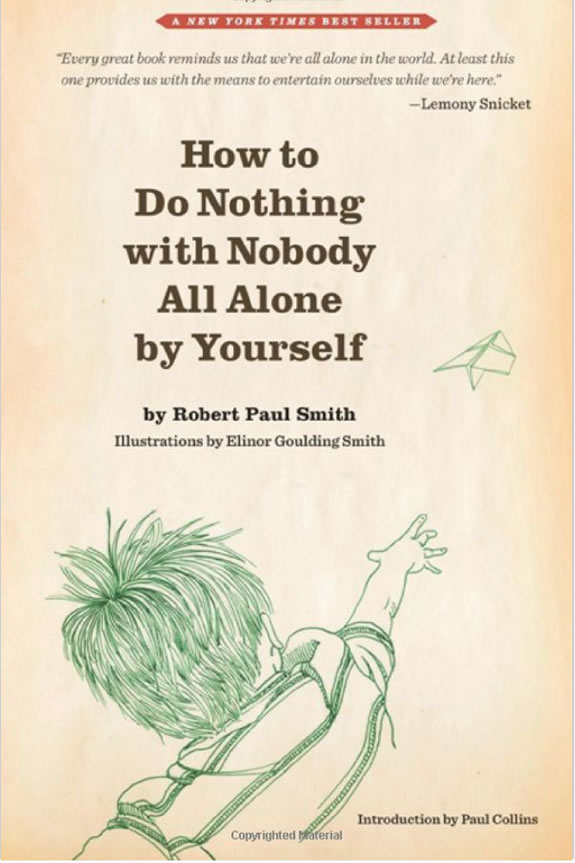

Sometimes that’s a book.

And that was — at 8 years old —

this book, published 1954.

I thought, “that’s me on the cover —

this is me, it’s my book.”

It was a beginning of another journey.

Get alone,

focus on doing nothing.

Or nothing much.

How to

Do Nothing

with Nobody

All Alone

by Yourself.

My mother never seemed to have a

worry about where I was,

but I did

like to be alone.

I never did well in school, so finding entertainments in the woods between school and home was an adventure unto itself.

I’d find an ant hill, a hornet’s nest, climb a tree, eat orchard apples, make structures, capture spiders to take to my room, look at things with my magnifying glass [and, decades later, I still carry one, every day]…

I’d look at things, under stones, inside logs.

I’d dig holes. Create caves. Light the caverns with candles. Walk my head through the grass, pretending [or presuming] that I could see like an ant.

Go

in

side.

That’s what this book is about — the simple pleasures of boyish kinds of things. Games with knives, whittling pencils, natural manipulations — fruit and chestnuts as objects of interpretation.

What it taught me about was knot-tying, bull-roarers, slingshots and craft — making things. Some of which, of course, might be regarded as forbidden by parental types. Knife throwing and slingshots weren’t endorsed. Much.

Worth exploring.

I go back to it.

And, too, it all comes back

in studying that string of influential memories.

Your journey goes forward,

but there are reminiscent markers,

that take you back to the beginnings,

from which your heart first opened,

signposts and messages

from the past that

reopen and continue

to point forward,

glancing over the shoulder.

You watch now, and you will watch later.

Remembering might come in those moments,

when you have nothing to do.

You’re spacing in.

Not

spacing

out.

You’re closer to your Self.

Not further,

a way.

Tim | GIRVIN WEST QUEEN ANNE STUDIOS

F i r e s t a r t e r & A c c e l e r a n t

B R A N D M Y S T I C I S M | Deep Journeys to Team & Enterprise

D i s c o v e r y: http://goo.gl/DNfwS9

It seems that you and Mark Twain have much in common.

Just great, oh can I relate. Not yet thirteen, I bought yet another cowhide drum in Swaziland, cowhide stretched wet over a tin drum and dried in the sun until bursting. I decided it would look neat with the FUR removed and began to scrape off the hair with my sizable pocket knife. Hard work as the fur is not meant to be removed from the hide. I sat there for three days in the sun, scraping until my arm ached and it was complete. It sits near my front door to this day, a seat, a surface for a coffee cup, a leg up to change a bulb.

For the first time our tools and entertainment are in the same device and so we develop fast-twitch capability. And culpability. I’m guilty, but conscious. I don’t want to waste the day. A star post, Tim!