The study of the Fifth Century Legacy

of Chinese Painting Scholar, Practitioner and Theorist: Hsieh Ho

“Energy is eternal delight”.

William Blake

Earlier in my career, decades back, I was exposed to the study of classical Chinese art theory and its applications to art, architecture and spiritual principles. This was connected to studying calligraphy and painting. Working with different masters, from China and Japan, I explored the context of Western approaches to illustration, type design and the treatment of the letterform.

And I applied it.

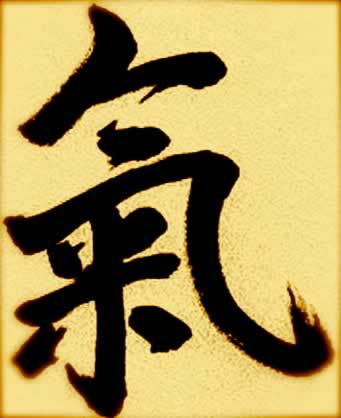

Cover calligraphy, Seattle Art Museum

The idea of capturing the spirit of the “thing”, is about literally reaching to spirit — the momentary essence of an object, as it is living and moving. And importantly, the breath of life that nourishes its vitality. Breath, in this context reaches to the heart of spirit. And that can be traced, etymologically, right to the essence of the word itself.

spirit (n.)

c.1250, “animating or vital principle in man and animals,” from O.Fr. espirit, from L. spiritus “soul, courage, vigor, breath,” related to spirare “to breathe,” from PIE *(s)peis- “to blow” (cf. O.C.S. pisto “to play on the flute”). Original usage in English mainly from passages in Vulgate, where the L. word translates Gk. pneuma and Heb. ruach. Distinction between “soul” and “spirit” (as “seat of emotions”) became current in Christian terminology (e.g. Gk. psykhe vs. pneuma, L. anima vs. spiritus) but “is without significance for earlier periods” [Buck]. L. spiritus, usually in classical L. “breath,” replaces animus in the sense “spirit” in the imperial period and appears in Christian writings as the usual equivalent of Gk. pneuma. Meaning “supernatural being” is attested from c.1300 (see ghost); that of “essential principle of something”.

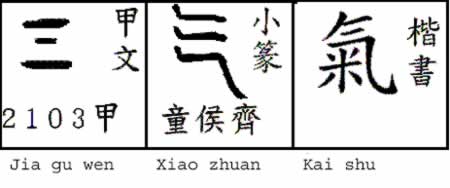

The essential character of ch’i is wrapped in the context of the calligraphic ideogram itself — as noted above — interpreted most memorably, at least for me, in the concept of the L-shaped stroke representing the “altar”, the four stroked treatment beneath speaking to the four elements, or the “rice grains” of the offertory — and above, the finishing strokes representing the vapor of the offering, to heaven.

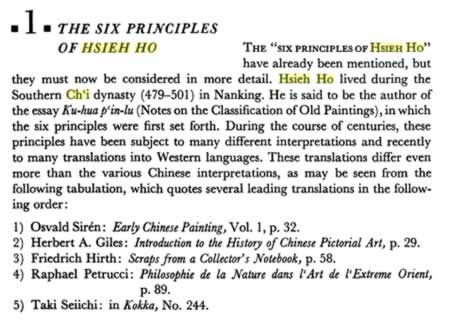

And the commentary and exploration of this sixth century grouping of precepts is extensive, and ranges into centuries of study and notations of interpretation.

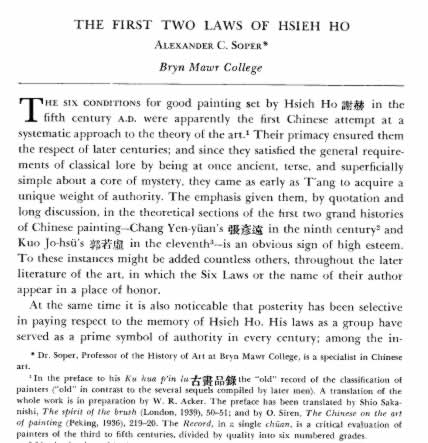

Alexander C. Soper’s “The First Two Laws of Hsieh Ho

Fritz van Briessen’s “The way of the Brush”

Or Clay Lancaster’s treatment, for the Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism

And there are dozens of others to be explored. But the point is about capturing, and illustrating — or literally, lustrating, the concept of the spirited energy of the object being expressed.

More than 1500 years ago, the notion of ch’i, however, was considered the most important quality in a painting by Hsieh Ho, of the fifth century, who put forward the Six Canons:

1. Infuse ch’i/yün to show life-movement;

2. Establish bone method in using the brush;

3. Respond to matter by creating form;

4. Distinguish objects by applying colors;

5. Arrange elements in appropriate positions;

6. Study earlier examples by copying them.

According to Wucius Wong’s “The Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting”, there are principles that are treasured. Classically, artist and art essayists have regarded these canons as the supreme guidelines in painting. The canons determine various goals of artistic pursuit, with the first canon having paramount importance. There have been numerous interpretations of this canon, but put in simple words

“it means that a painting should breathe with life.”

In varying interpretations, ch’i and yün either represent separate concepts or stand as a single term. Ch’i, standing for breath, incorporates such meanings as spirit, energy, and force, all used in a cosmic sense. The Chinese character yün can mean organic harmony, concord, charm, resonance, or rhythm. When ch’i and yün function together as a single term, the term refers to the vital breath of harmony, incorporating the meanings of both characters.

The whole phrasing for the opening canon is: “A true work of art should express the rhythmic vitality of the breath of heaven”.

How, possibly, might this be linked to the notion of design, or identity, for application in any environment of communications? Esoteric yes, but relevant, surely. The point reaches to the context of “lustration”, the idea of capturing the spirit of an entity – which could be an enterprise, a product, a concept of expression.

When I work, I tend to consider the relationship

with my clients as a kind of

meditation.

It’s a settling in, a contemplation into their world, and being there, being absorbed in that reflection allows me, and the team at Girvin, to mindfully gather in their sense of culture. That embrace draws me into their audience, their place of experience — and that brings me into proximity to make what we create for them “shine”. More so, it’s a captivation of spirit, going back to the beginnings of the notation — it’s breathing in, and exhalation of the character of the brand, the fire, the soul, the vitality that is critical to the nature of building resonance in community, in communications. And the illustrative link?

illustration

c.1375, “a spiritual illumination,” from O.Fr. illustration, from L. illustrationem (nom. illustratio) “vivid representation” (in writing), lit. “an enlightening,” from illustrare “light up, embellish, distinguish,” from in- “in” + lustrare “make bright, illuminate.”

What could be more, to the nature of identity, than to create that bridge from heart, to fire, to lighting the message from the inside, to the outside, in moving forward in change?

It’s fluency, flow, energy catalyzed.

Image credit: Shinichi Maruyama

tsg

—-

E x p l o r i n g f i r e b r a n d s:

https://www.girvin.com/blog/brandfire/

References:

Google book: The Way of the Brush

Scholarship:

http://www.jstor.org/pss/2049541

http://www.jstor.org/pss/426036

Wong, Wucius. The Tao of Chinese Landscape Painting,

Principles & Methods.

New York: Design Press. 1991.

Girvin ch’i references:Calligraphy

Painting books

Journals:

Girvin and Ink

Meeting a Zen master

Etymology:

lustration