The design heritage of the Indiana Jones franchise.

Reaching back into the deep territory of my imagination — and my history as a long-running movie goer, I stride the aisles of Fox Theater, downtown Spokane, the 60s — and riding the buses alone, seeking the filmic, forbidden adventures of my childhood. Going downtown by myself wasn’t allowed, nor was seeing some of the movies that I’ve seen — and the only way to do it, was to get there, get downtown, get in. Even sneaking in. And seek the shrill adrenaline of the adventure, the sci-fi realms, the horror film — always on a Saturday, always amidst crowds of other kids.

How they got there is unknown — but it was a gathering, a magnet for that transport to other worlds, fearsome, wild, unseen, unexpected and otherwise captivating. I am not alone. That memory of early connection is shared — even James Cameron recalls:

“When I was a teenager, in the late sixties, we were literally sending people to the moon. The line between fantasy and reality was starting to blur. I’ve always tried to stay in that blurry space, that nexus between the flights of fantasy and what you can really do at the extreme edge of human experience.” And that magnetism, that adventuring spirit, in youth to the theater is more than just moving images: “I know as a filmmaker and as a fan that movies do have a profound effect on you—mentally, emotionally, and physiologically. Your respiration probably goes up, you get a shot of adrenaline, you jump out of your seat. If it’s a scary film, maybe your endocrine system is in high gear.”

What I’d been curious about, in the return of the latest installment of Indiana Jones, (incidentally involving Cameron — “The Raiders of the Lost Ark”) is the character of this brand, amidst the history of all the other branded, cinematic entertainment, in the past. What of the present — this most recent Spielberg | Lucas unearthing of the fourth archaeological enterprise? Really, what’s the heritage of this type of cinematic storytelling? Surely, there’s a timeline in reference — there’s a real “period” character that’s revived. Where did it come from?

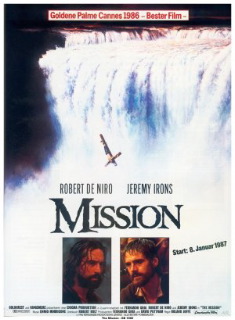

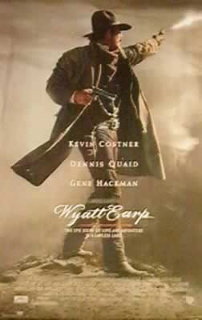

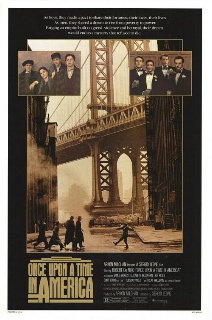

Over the course of a number of years, I’d worked on films that we inherently created for period expression. That is — designing them for timely, chronological accuracy. That might be work like this:

The roughly hewn roman drawing of The Mission, here in the Italian adaptation:

Or the hand-tooled replication of the pistol engraved signature of Wyatt Earp:

The deco rendering Once Upon A Time in America, that we’d created for Sergio Leone (originally a pitch package design for funding for the project).

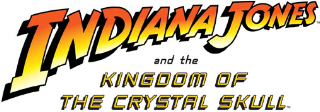

The Indiana Jones vehicle fits into that space — a sense of illustrated chronology — marketing a distinct period, recreating adventure, pulp, matinees and serialized entertainment and the branded look and feel of that era.

Inherently, motion picture branding is resolving the best — and most currently intriguing — method of telling the story, in the compressed space of print advertising, teaser cinematic expressions and broadcast — theatrical advertising presumes that coherence. I’m sure you get that — it’s fundamental to promotion. But this is less about that — and more about the legacy of how Indiana Jones came to captivate — and rejuvenate — a certain genre. Here’s more on that.

First, the identity:

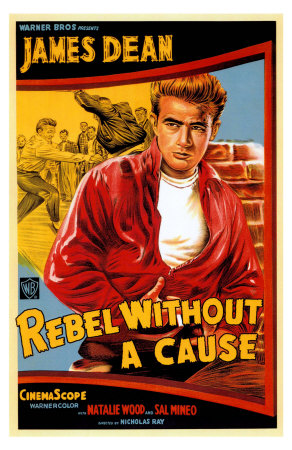

And you can easily see the stylistic leap between the characteristic an all caps, italicized rendering that harkens from the 30s onward — it’s a way of dramatizing the concept of action, mayhem and adventure all rolled into a kind of swashbuckling stance of scripted swagger. And, off hand, a quick reference here is to a film that speaks this language — for many of us, an eye-opening saga of extraterrestrial encounters.

And the telling reference to Indy styling is in the headlines that presage the campaign, spawned 1951 — note SPELLBOUND:

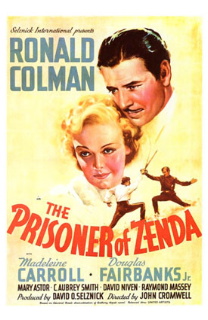

There are other characteristics to the adventure visual drama, even stretching back, stylistically to 1937 — Ronald Colman‘s appearance in The Prisoner of Zenda.

This earlier branding link uses a dramatically splayed typographic treatment, with the same notched lettered detail — note the P and Z, for example.

And it goes back…

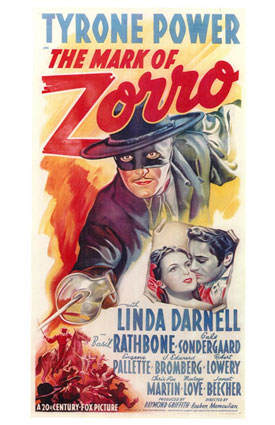

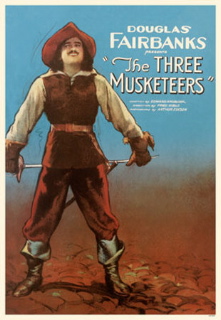

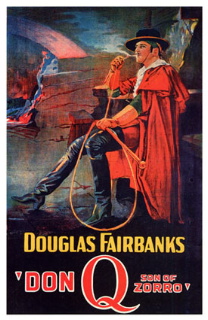

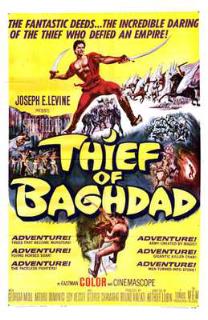

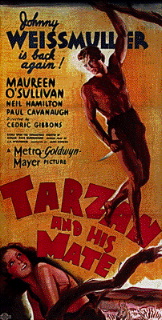

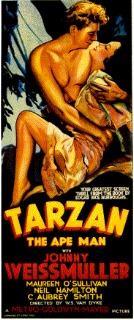

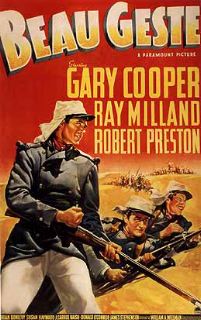

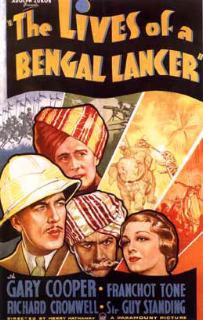

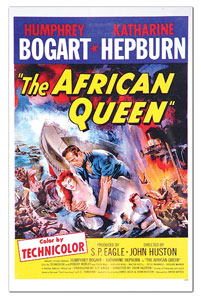

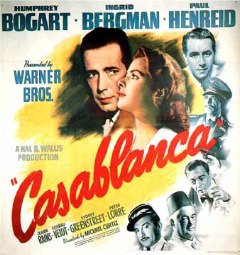

But it’s more than just style, it’s content. And the content is all about adventure and outlandish worlds — action and wildly envisioned set designs and thematic explorations. And the whole world is rife with possibility. Just the string alone of adventure is a literal history of film. Individual directors often associated with adventure films include the trailblazers — Cecil B. DeMille, Henry Hathaway, Michael Curtiz, Howard Hawks, John Huston, David Lean, Zoltan Korda, and Raoul Walsh. The major adventure film stars through the decades of action have included Douglas Fairbanks Sr. (and Jr.), Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Johnny Weismuller, Tyrone Power, Gary Cooper, Stewart Granger, Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Charlton Heston, Alan Ladd, Sabu, Cornel Wilde, and then in the last thirty years — Sean Connery, John Wayne, and Harrison Ford.

It goes back even further, to the seeds of imaginative fertilization — the 20s — beginning most significantly with Douglas Fairbanks, who catapulted efforts in adventuring, set the opening athletic pace. This opening framing sparked in the teens, ignited in the 1920s — with added performances extended by Errol Flynn, Tyrone Power and others…(and I’m sure there are many scholars who might bridle at my gestural focus to definitive history).

While these opening Fairbanks poster offerings are rather tame in the initial expression of adventure — the staggering juxtaposition of image and type sets the stage for forthcoming decades of adventure brand design.

And the design and physicality flows — Weissmuller, the 30s:

These typographic treatments begin to speak the styling of the adventuresome. There’s a dramatic play to the image, the titling rendering leaps over the one sheet.

These later designs follow on, and expand that line of branded adventure design thinking — the push becomes more pronounced.

That added dimension continues to evolve, moving into the forties and a string of powerfully balanced imagery of the protagonist, exotic locale and color-drenched illustration. And there’s a reach back from Indiana Jones to these tellings, Bogart in play, even in two separate renderings of promotional context:

Or this splashed, dramatic scripting of this titling, Casablanca:

There’s a quality that lays the ground work for the branding design of Indiana Jones — and it extends to the realm of the serialized adventure, the Saturday matinee, a pulped visual mission. But the concept of one story leading to another, in dramatized thrillers, steps back to Victorian times. The notion of serialized writing captivating the audience of readers begins with Sherlock Holmes. Read this story and come back soon for the next installment. And indeed — millions on millions did just that. And still do!

The original character, Holmes — grew tremendously in popularity with the beginning of the first series of short stories in The Strand Magazine in 1891; further expositions of short stories and two serialised novels appeared right up to Conan Doyle‘s death in 1930. The legendary tellings cover a period from around 1878 up to 1903, with a final case in 1914. That is, perhaps coincidentally, the breaking open of the box of serialized filmic storytelling.

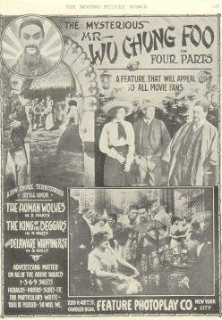

This crossed over to filming productions — creating small grouping of repeating story lines that climax and conclude, leading the viewer onto the next installment. It’s an enticement, an addictive bewitching. A reference might be — to the genre that we’re exploring — first celebrated in The Mysterious Wu Chung Foo — the inscrutable embodiment of evil-doing — early 20th century.

Then evolved to the serialized matinee — Fu Manchu, the 20s.

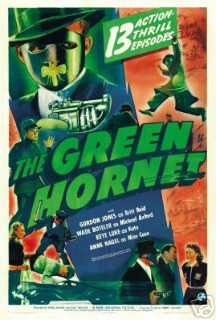

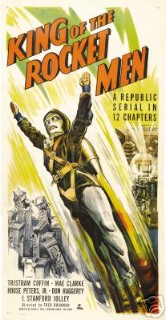

And, to other matinee, mini-storied tellings, there are the proverbial classics — and each, in a way, sets the tone for the stylistic embrace of the Indiana Jones heritage.

I can recall all of them. I can taste the sheer exhilaration of heading to the bus stop, waiting for the right number — (figuring that out!), getting the show time and the theatre stop off aligned and making my way into another world. Along with the throngs of other kids, all carousing in the sheer adventure of it all.

The legacy of Indiana Jones is a celebration of all that. For Time Magazine, Steven Spielberg noted: “I dream for a living. I use my childhood and go back there for inspiration” As blogger Michael Peters references,

“This idea of dreams and imagination is a key contributor to the legacy of Spielberg as an artist. There has been no one that has relied more heavily on the idea of fantasy and all its wonderment (maybe George Lucas) than Spielberg. His films are about spectacle, wonder and emotion but yet are defined by a recognizable humanity. His films are about the average human being (the everyman) and their collision with extraordinary moments or situations.” To the analysis, Peters further notes, of James Clarke, (The Pocket Essential-Steven Spielberg, 2001), these moments “challenge, test and identify the everyman who confronts them and thus becomes consumed by them. As a result, characters learn and are illuminated by their own potential.”

Reach deep — find the adventure, your self –renewed. Find your own “hero of a thousand faces”. I’m sure Joseph Campbell and C.G.Jung would jump all over that presumption, in the array of legendary archetypes explored above.

Articles of reference:

Michael Peters (Suite101.com)

http://www.suite101.com/profile.cfm/mpeters799

History of Indiana Jones

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indiana_Jones

Action-adventure film history

http://www.filmsite.org/trea.html

Poster references

http://www.allposters.com/

The story of the Crystal Skull

http://www.aintitcool.com/node/33975

Fu Manchu references

http://www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

NYTimes review of Indiana Jones

http://movies.nytimes.com/2008/05/22/movies/22indy.html?8mu&emc=mua1

The Day the Earth Stood Still

http://www.moviediva.com/MD_root/reviewpages/MDDayEarthStoodStill.htm

Movie Poster search tool

http://www.learnaboutmovieposters.com/

What influences you? What opened? What new cause uncovered?

—-

Tim Girvin

GIRVIN

New York City + Seattle | Tokyo

https://tim.girvin.com/

D.logs:

https://www.girvin.com/blog

https://tim.girvin.com/index.php

Exploring storytelling, brand, film.